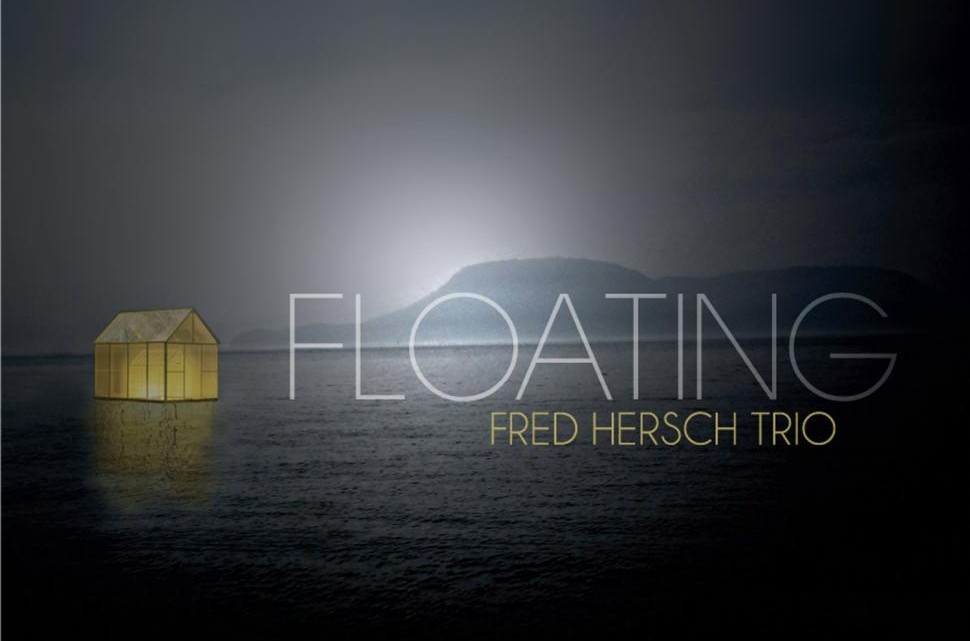

So I was levitating from the sheer beauty of a performance by The Fred Hersch Trio during a concert in Ohio when all of a sudden Hersch drew appreciative applause from the audience when he introduced his new composition, “West Virginia Rose.” The applause arose not only because of the floral charm of naming the tune after his mother Florette and his grandmother Roslyn, but also because Hersch acknowledged his home state of, no not West Virginia where his grandmother lived, but Ohio where he grew up. During its one-second-over-two-minute duration, the wistful, respectful “West Virginia Rose,” with its unabashed folk-influenced tonic center, traces Hersch’s roots back to the simplicity of song, the origin of so much music, before he immersed himself in classical training and then built his reputation as one of the original, not to mention one of the most celebrated, jazz piano voices of his generation. “West Virginia Rose” is noteworthy also because it’s the first time I know of that Hersch paid tribute to members of his family.

But then Floating, Hersch’s first studio recording in four years, is an album that contains an abundance of tributes. As I listened to the trio’s newly released album, compliments of the diligent Ann Braithwaite, I realized that, OMG, the Ohio concert was a preview of this recording. When Hersch notes that the CD’s song sequence reflects that of a live performance, indeed it was a live performance that foreshadowed the studio recording in Yonkers, set up as if it were recorded live. Yes, I remember from the concert the final number, “Let’s Cool One,” and recognized that Hersch often closes his concerts with a Thelonious Monk tune, and there’s “Let’s Cool One” as the final track of Floating. Hersch’s touch and voicings and modulations and the warmth of his sound remain his own with no apparent influence on those characteristics from Monk, and one wonders why Hersch demurs with comparisons to Bill Evans. Yet, Hersch’s playfulness of imagination and plinking ninth chords from adjacent notes and his stretching of tempo and his pinpointed outlines of melody and his individualism of rhythms borrow from Monk, as Hersch demonstrated on his solo album, Thelonious: Fred Hersch Plays Monk.

I mentioned Hersch’s thoughtful dedications on Floating, and the most poignant of these is associated with “Far Away,” written in memory of drummer Eric McPherson’s wife, Shimrit Shoshan, who passed at the age of 29 in 2012. Quietly introduced by McPherson with shimmering cymbals of varying pitches, “Far Away” attains Hersch’s meditative rhythmless counterpoint woven into an emotional remembrance, punctuated by McPherson’s soft malleting. Noticeable throughout the album, and especially on “Far Away” and “If Ever I Would Leave You,” is his piano’s purity of sound, the pealing and sustained values of his treble notes. While this may be attributable to Hersch’s acknowledged touch technique, it also suggests that he chooses to record on well-tuned, top-of-the-line pianos and to work with trust sound engineers, in this case James Farber. Indeed, some of Hersch’s passages on Floating sound as if they could have been recorded on some of his albums of twenty years ago, so similar is the ringing, unmuddied sound.

Even bassist John Hébert, a Baton Rouge native, receives his own song too, “Home Fries,” on which Hersch develops his own interpretation of a New Orleans groove, with its galloping bass notes and plenty of rests to allow for Hébert and McPherson to heighten and vary the rhythms. “Arcata” recalls Hersch’s work with bassist/singer Esperanza Spalding with her playing’s bounding, energetic brightness as the composition combines a tribute to Spalding’s home state of Oregon with the fluid sweeping bass lines characteristic of her playing—quite an honor from a pianist who has performed with some of jazz’s top bass players. “A Speech to the Sea” was inspired by the work of Finnish artist Maaria Mirkkala, as was the cover photograph on the album’s cover, as Hersch performs with the affecting combination of song, classical references, jazz harmonies and rhythmic elasticity. “Autumn Haze” is a dedication too, this one to pianist Kevin Hays, the modulations thornier and more unrooted than “West Virginia Rose’s,” with unpredictable chord movement that defies and accommodates logic.

One song rounding out the “live performance” choice of music for Floating is the opening track, “You and the Night and the Music,” which pulls in the audience with its familiarity of melody and its variation of rhythm and improvisation as Hersch’s trio launches it into a propulsive six-eight whirl whose key change could escape notice, so effortless it is. And then there’s “Floating,” a beautiful title track that consisting of minimal chord changes and an uncomplicated melody that allows for the musicians to complement each other’s spur-of-the-moment ideas, whose colors no doubt change kaleidoscopically with each performance.

With new music written at Civitella Raineri in Italy and recorded in New York state and, fortunately for me, performed in Ohio for live and now recorded appreciation, Floating documents Hersch’s present trio with Hébert and McPherson. Furthermore, it provides documentation that Fred Hersch remains one of the premier, individualistic and most influential jazz piano players entrancing audiences worldwide. I was one of the entranced.

2014

Artist’s site: www.fredhersch.com

Label’s site: www.palmetto-records.com