All good things must come to an end, unfortunately. That’s part of the process of regeneration, I suppose, which is how the world continues to be refreshed. Nonetheless, it’s a sad occasion when it’s time to move on. Now, Dreambox Media, a label documenting Philadelphia jazz the way the musicians wanted it recorded, has called it quits after thirty years in the business.

Uncompromisingly dedicated to the individuality of jazz and its uncontainable spontaneity, Jim Miller, the founder of Dreambox Media, allowed the musicians and the vocalists of Philadelphia to record under the circumstances that they desired, and not according to the dictates of a major label’s A&R coordinator. Such independence had its advantages and disadvantages. Advantage: The artists controlled their own recordings as part of a cooperative venture, and so they were responsible for the final result without being distracted by the marketing and production responsibilities provided by Miller. Disadvantage: The artists controlled their own recordings as part of a cooperative venture, and so they are responsible for the final result. In other words, more risk exists when artists record on a local label. Even so, the results may be more rewarding as they reflect more genuinely the artists’ visions.

The influence of Dreambox Media can’t be underestimated, as it took chances on, or continued to record, dozens of local jazz performers, many of whom are well known like Orrin Evans, Shirley Scott, Uri Caine or Mickey Roker. Others like Larry McKenna or Evelyn Simms remain well known within the Philadelphia community, but not so much outside it. Since the musicians and singers made the decisions about their own recordings, the label’s albums represented their own personal statements. So, Dreambox Media has developed a discography that provides a virtual history of much of Philadelphia’s jazz in the past three decades.

But, the music business being the music business, sustainability remained a challenge, as it has for even much larger labels or entertainment companies. The Internet—and specifically Apple Music, YouTube and apps like Spotify—upended the traditional process of payment for personal musical access, thereby making the costs of album production difficult, to say the least. Rather than switching to a GoFundMe-like or ArtistShare-like alternative, Miller decided that Dreambox Media had had a good run during a time that was right for physical jazz recordings.

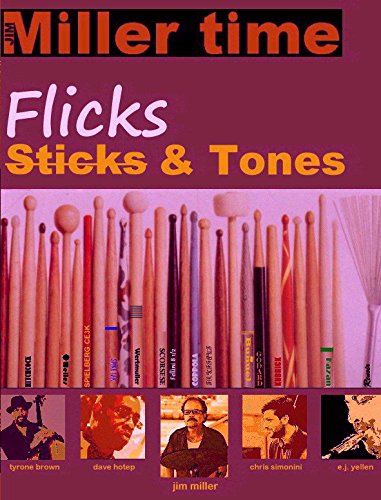

And so, instead of going out with a whimper, Dreambox Media went out with a band. Working with recording engineer John Vines, Miller Time performed the final Dreambox Media release at an April, 2015 concert at the Edelman Planetarium at Rowan University. Who knew at the time of the concert that the end was near? Maybe Miller didn’t know that himself. Over a year and a half later, the Edelman Planetarium concert would re-state Miller’s intentions for Dreambox Media: namely, that the entity would allow, to the greatest possible extent, all types of artistic endeavors, including visual as well as musical.

This last release combines those elements. Miller coordinated the six musical selections of the Rowan University concert with images—some enlightening, some ironic, some of social concern, some whimsical, some frightening—that illuminate the musical concepts his group suggests.

“In One Ear, Out the Other” tackles nothing less than the omnipresence of warring throughout the history of mankind. The pulse and infectiousness of the music belie the seriousness of the topic, for the instrumentation doesn’t attack as much as invite with its modal buoyancy. As the band plays on, the world turns. While Miller revisits the brutality of the opening scene of simians from Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, he takes a different conclusion from the bone/weapon thrown in the air. Kubrick showed the development of human progress in the next scene; Miller shows that nothing has changed. With rapid-fire dates of wars over maps showing varying regions of the world, “In One Ear, Out the Other” tracks the unending use of weapons, represented by the ape’s killing and vandalizing bone, from 2500 BC to the present. Kubrick warned of the perils of technology. Miller warns of the perils of human nature, as he quotes Bertrand Russell’s observation about brutality.

One wonders if the audience at Rowan University was aware of the inspiration for “In One Ear, Out the Other,” its music more calming than its message.

You get the idea. Miller and his quintet throw out a final statement of their thoughts without apology or softening of its presentation, much as Dreambox Media has done, unfiltered, throughout much of its existence. The next track, more of a groove than modal soundscaping, presents jazz as a civilizing force—a belief that the musicians bring to life with E.J. Yellen’s tenor sax work. Though the segment begins with images of Duke Ellington, Lester Young, Billie Holiday and others, it moves into “duck and cover” films in preparation for nuclear attack in the 1950’s, an event which thankfully never happened. Nonetheless, at the time, the very thought of nuclear scared the entire population, and the DVD’s message implies it was in need of artistic achievement to achieve some peace of mind.

Not only does Miller’s swan song, Flicks Sticks & Tones, preserve a concert for posterity, but also it provides for posterity Miller’s unvarnished beliefs, delivered without a word, during the year of Dreambox Media’s exit. “Nostalgia for the Future” addresses income inequality to Chris Simonini’s electronic keyboard improvisation, and it depicts scientific achievement with Dave Hotep’s modal understatement on guitar. Quickly edited images contrast slum housing with new luxury apartment construction, abandoned factories with promises of robotized industrial automation, before they lead into the celebration of man’s landing on the moon.

But the DVD isn’t entirely message-driven. “Like up in the Sky” considers the wonders of the cosmos, as did Kubrick, with scenes of stars and constellations and planets as the group tries to capture musically the ineffable vision of life beyond earth, perceptible but incomprehensible. “The Fellini’s Mutual” is dedicated to the memory of a guitarist important to the label, Jef Lee Johnson, who appears to have been an aficionado of classic movies, as is Miller. Accordingly, that track includes film clips of scenes of distress, some from silent films. Indeed, Flicks Sticks & Tones is packed full of classic movie scenes from the likes of Godard, Eisenstein, Scorsese, Truffaut and Spielberg. The final scene of “The Fellini’s Mutual” parodies one of Hitchcock’s most famous.

Despite the darkness and despair of much of the theme that precedes it, the eleven-minute final track, “How about This?” wishes for peace. Musically expressed of course, that wish appears as the word “Peace” translated into native languages over successive flags of numerous countries. While that wish apparently has been unrealized for four thousand years, according to the DVD’s chronology, it appears to be a wish worth retaining, as reminded by Flicks Sticks & Tones. How else can human nature be kept in check?

That forthrightness and feistiness, missing from the recordings of entertainment conglomerates, explains why Dreambox Media will be missed. It already is.

2016

www.dreamboxmedia.com