Finding a CD featuring jazzy interpretations of King Crimson’s ‘Matte Kudasai’, Joe Jackson’s “Stepping Out”, and Stevie Wonder’s “Golden Lady”, among others, should not, on the face of it, be too much to ask for.

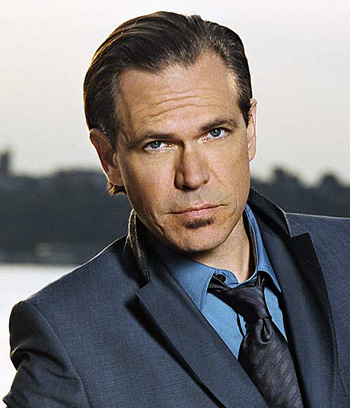

However, with the recording industry obsessed with labelling and pigeon-holes, demographics and focus groups, such a one-stop collection of renditions normally eludes the grasp of discerning listeners. Thankfully, through the pairing of legendary producer Don Was’s artistic conception with swanky vocalist Kurt Elling’s rich baritone, jazz fans are able to enjoy something borrowed from the not-too-distant past which possesses more than a hint of the blues. It all comes together on a classy CD titled ‘The Gate’, which also includes the singer’s poignant dedication to his young daughter, ‘Come Running To Me’.

Alongside his long-time pianist, Laurence Hobgood, Elling is joined by a constellation of jazz stars including Marc Johnson, John Patitucci, John McLean, and Bob Mintzer.

Elling shared his views on the new album and on his approach to jazz in an exclusive interview for www.ejazznews.com.

John Stevenson: Do you see yourself as being a vital contributor to the so-called “New Standard”?

Kurt Elling: I don’t know if I’m a vital contributor to anything. I do think it makes sense that contemporary artists are increasingly lending their own treatments to contemporary and near-contemporary material. In the 1940’s, 50’s and 60’s, jazz artists routinely went to contemporary compositions for raw material. Now those songs have been enshrined in routine parlance as ‘THE GREAT AMERICAN SONGBOOK’. But at one point they were just show tunes and stuff from the hit parade.

JS: Don Was makes a big fuss over his experience of listening to you for the first time. Were you as aware of him and ‘Was (Not Was)’?

KE: I was (no pun intended). I am very happy to have been adopted by Don. He is a true lover of all kinds of great music and has become a dear friend to me.

JS: On ‘The Gate’, you nailed that wistful, dusky, mood conjured up in ‘Blue in Green’. What were the challenges in dealing with the stylistic nuances presented by a song like that from 1959, and more contemporary fare such as Earth ,Wind & Fire’s ‘After The Love Has Gone’, and King Crimson’s ‘Matte Kudasai’?

KE: From my perspective, the process is pretty much the same. I listen to my intuition for melodies and lyrics I can believe and feel that I would like to sing. I listen again to my intuition to hear what new idea I might be able to bring to the piece to make it new. Then I work intellectually to bring the ideas into a unified gestalt. I’m not really concerned in this process, of a piece’s birthday, provenance or age. It is strictly a matter of whether the new idea is good, whether I am musician enough to see it to fruition, and whether the final performance stands up to factors of quality control.

JS: The closer, “Nighttown, Lady Bright” is an evocative one. The spoken word portion of the tune featuring both your own lyrics as well as Duke Ellington’s, confers on it an almost movie-like quality. To what extent, however, does it help to reinforce clichés of the jazz life?

KE: Playing off clichés reinforces their existence. But clichés exist because – to some extent – they are true. I am happy that I have personal, intimate memories of the experience of driving/being driven/walking home after an evening of performances in jazz venues in the early morning hours, when the city is alight, the streets are mostly empty, and I hear the whispers of poetry in the breath of the urban night.

JS: You describe ‘Come Running To Me’ as a gift to your daughter. Has she changed your approach to your art and craft?

KE: Not so much my approach, but my attitude. I am a much happier, less rage-filled person than I have been in the past. A family filled with love is a civilizing energy.

JS: You were a graduate student at the University of Chicago before the release of your critically acclaimed 1995 Blue Note disc, ‘Close Your Eyes’. Has your performing career eclipsed your academic studies altogether? How have your studies in divinity affected your artistic pursuits?

KE: Clearly my writing and performing career has moved to centre stage and pushed any professional aspirations in the academic world off entirely. I don’t routinely get requests for interviews from ‘Criterion’, ‘Tikkun’ or ‘Christianity Today’. I pursue many of the same questions through art, instead of through the deconstructive debate and analysis of texts.

JS: There aren’t many headlining male jazz singers at the moment. Certainly not many signed to the major labels. Why do you think this might be so, and, do you see yourself as a role model?

KE: There are many reasons there are not more male jazz singers. There is no money in it, for one thing (Michael Bublé and Jamie Cullum notwithstanding). The fact that tastes and fads in music change. Once Sinatra’s music became ‘your parent’s music’, that killed off whole generations of potential jazz singers. The lack of quality music programs in most schools is a factor. Am I a role model? Perhaps to a small segment of college and conservatory people. Mostly, I think of myself as a devotee or a student myself.

JS: How enriching has the Chicago jazz scene been for you, and, what makes the jazz scene in the Windy City unique? How does it contrast with the Big Apple’s jazz vibe?

KE: Chicago is the city where I became an artist. It invited and fed me. I was fed by the root system of the Chicago scene and will always think of myself as a Chicagoan.

JS: Laurence Hobgood is a player of great sophistication and sensitivity. Have you helped him to enhance his artistry in the same way that he has affected yours?

KE: I hope so. I believe we have very complimentary gifts. Where I am more direct, he is labyrinthine. Where I wish to simplify, he wishes to orchestrate. Where I naturally hear and gravitate toward poetry and lyrics he naturally gravitates to non-verbal, harmonic communication. But we, each of us, have strong enough doses of the other ends of the spectra to be able to communicate thoroughly and to trust the other’s opinion.

JS: Your work references folks like the Beats and novelist Ellmore Leonard in parts. Indeed, some of the projects you’ve taken part in like Fred Hersch’s Leaves of Grass (a dedication to Walt Whitman) confirm that you bring a literary aspect to jazz. Is it important for a jazz vocalist to have this kind of literary perspective?

KE: I think it is important for a jazz vocalist to develop her or his intuition, intellect and sense of self just as she or he develops artistry and craftsmanship. One must have a sense of one’s identity, place and time in the world in order to have a coherent, searching point of view. Whether that comes through poetry, an experience of nature, capoeira, or what have you, is a matter of what the artist in question has as a starting place.

JS: Do you plan to bring out a jazz album of your own songs in the near future?

KE: My collaborator, Laurence Hobgood, and I, are more or less continually engaged in the process of creating new material.