The Jimmy Heath Big Band

GET YOUR COPY NOW

“Togetherness brings generations and cultures in sync.” – Jimmy Heath

What Jimmy Heath said about his latest album—his third big band album and first live big band set—can be applied to jazz itself, one of these most inclusive of the Arts. A big band can be one of the finest examples of a jazz as an art form, a framework that achieves a balance of precision, unity, focus, and personal expression.

Jimmy Heath is of a jazz dynasty, the House of Heath, if you will: Jimmy; brother bassist Percy, and brother drummer Albert, a.k.a. “Tootie.” Saxophonist (tenor and soprano, also flute), composer, arranger, and bandleader Heath’s 2010 memoir is entitled I Walked with Giants, and that title/claim is hyperbole-free. Before becoming established as a force in his own right, Heath’s career was intertwined with Dizzy Gillespie, John Coltrane, Miles Davis, Clifford Brown, and Milt Jackson. Not becoming as “famous” as these iconic figures is, according to Heath, beside the point. “You become an icon when you’re dead,” opines Heath. “I always say I’d rather be an acorn, and be alive.” As most of us recall from science classes, the mightiest and most enduring of trees began with an acorn, and Mr. Heath is one of America’s greatest living examples of that.

Born James Edward Heath in 1926, he is one of the exponents of one of the greatest jazz municipalities that isn’t New York City, Detroit, Kansas City, or Chicago—namely, Philadelphia. Aside from those tasty cheese-steak subs, Philadelphia has been a habitat that’s produced John Coltrane, McCoy Tyner, Pat Martino, Uri Caine, and Kevin and Robin Eubanks. Raised on the sounds of the great big bands—including those of Duke Ellington, Earl “Fatha” Hines, and Glenn Miller—and fueled by the then-strange new music that came to be known as bebop, young Heath was such an acolyte of bop prime mover Charlie Parker that at the tender age of 20, Heath—then an alto saxophonist—was known as “Little Bird.” Call it a good burden: “I liked the idea at first, but I wanted to be Jimmy Heath. So, I say, ‘Well, I’ll get the tenor and try this.’” In 1948, at 21 years of age, he performed in the First International Jazz Festival in Paris, sharing the stage with Coleman Hawkins and Errol Garner. But he had the urge to become what the Duke referred to as a “pencil cat,” composing (many great) tunes and writing arrangements. Parker himself played Heath’s original “Fiesta” and Miles Davis recorded his “Serpent’s Tooth.” In 1946-47, Heath had his own big band that, alas, went unrecorded. But this band proved to be a watershed—it became, in Heath’s words, a “feeder band” for Gillespie’s big band: Coltrane, Ray Bryant, Johnny Coles, Benny Golson, and Specs Wright were members, and Heath’s big band was a “gateway” into his mentor Gillespie’s orchestra.

Togetherness is firmly in the tradition of the classic post-Swing Era big bands. That was a transitional time where big band jazz became less a dancer’s music and more a listener’s music yet still retained the joie de vive and grand, compelling swing of the great jazz orchestras. While the post-World War II economics put a serious crimp in the viability of the popular big bands, many soldiered on and some even thrived into the 1950s and even the ‘60s embracing this new music called bebop. These include: Dizzy Gillespie, who had a fantastic band 1946-1950; in the early and mid-‘50s Count Basie had quite the renaissance, his big band invigorated—stylistically and in popularity—with the modern arrangements by Ernie Wilkins, Neal Hefti, and Quincy Jones. Gil Evans, already established with Claude Thornhill and Miles Davis, was coming into his own with a big band that had a foot in the jazz tradition and both eyes to the horizon. In the 1960s (and beyond), Thad Jones/Mel Lewis, Woody Herman, Gil Fuller, Gerald Wilson, and the UK’s Johnny Dankworth may not have set the popular charts afire but they blazed brightly, swinging hard and smartly during a time when some ill-informed souls declared that jazz, especially of the big band variety, was “dead.”

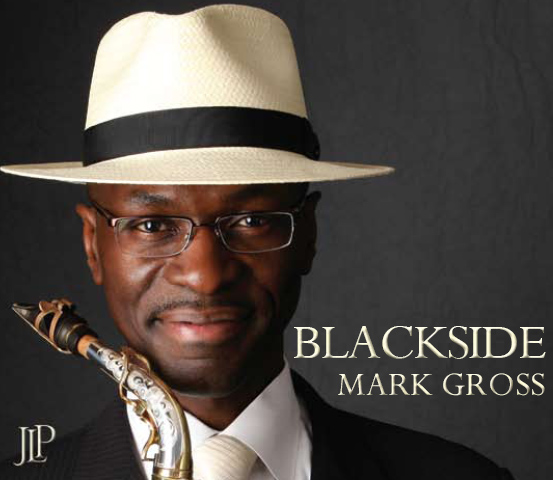

Togetherness is in no way a nostalgic voyage into some idealized past—while it draws upon the voicings, swagger, and opulent orchestrations of the classic sounds of the Basie, Gillespie, etc. large organizations, it’s music of the here and now. Heath’s big band features former students (Jeb Patton, Antonio Hart, Diego Urcola), some fiery young aces (Mark Gross, Greg Gisbert), and a couple of veterans (Charles Davis, Steve Davis). Recorded live at New York City’s famed Blue Note, Togetherness roars to life with Heath’s original “A Sound for Sore Ears,” a bright, brassy mid-tempo charger that sets the mood for the entire album: Full-bodied, spectacularly rich and imaginative arrangements for horns and reeds; urgent and undeniably modern, edgy soloing, and irresistible, Saturday night-on-the-town swing. “Sound for Sore Ears” evokes the dry wit and urbanity of The Bennies—Benny Golson (a fellow Philly-ite and member of Heath’s big band) and Benny Carter, two great saxophonists and brilliant arrangers who ace orchestrations have brightened many a TV and movie score. “A Time and A Place” is a funky strut evoking the soul-jazz grooves of the glory days of Horace Silver, Young-Holt Unlimited and Lee Morgan’s “Sidewinder” (especially with the bristling, seething solo by Roy Hargrove, nodding to both Morgan and Maynard Ferguson). The evergreen “Lover Man” is a slice of yearning balladry lent savor by Heath’s tender yet resolute solo and the plush sway of a noir-tinged arrangement loaded with old-school glamour—one can imagine the camaraderie of Sammy Davis Jr. and Frank Sinatra (both of whom recorded with Basie) at the Sands, the perspiration on their drink glasses and the clink of ice cubes therein.

Togetherness embodies Heath’s proud yet factual statement, bringing together many aspects of his musical life and of jazz: Composer, arranger, player, and educator, embracing and extending jazz’s big band tradition, all “in sync.” Be on the lookout for the band’s future performances at the Blue Note and Heath’s next project, his first as an arranger for a vocalist, Roberta Gambarini, and in May, Heath will be the object of a cover story in downBeat. At an age when he could be forgiven for resting upon his laurels, Jimmy Heath will have none of that—he’ll be on top of things, as he so succinctly puts it, “until he leaves.”

GET YOUR COPY NOW

OurGig.com | PR Services

www.ourgig.com

pr@ourgig.net