Lionel Hampton, Red Norvo, Milt Jackson, Terry Gibbs, Roy Ayers, Bobby Hutcherson, Peter Appleyard, Jay Hoggard, Gary Burton, Joe Locke, Steve Nelson, Stefon Harris, Warren Wolf, Joel Ross.

The list of major jazz vibraphonists is brief, but their jazz contributions to the instrument’s status progressed through the generations as their styles and techniques advanced.

A review of the list indicates that each vibraphonist delivered an approach that, even though it may have built upon those of the predecessors, reflects individual personality.

Cal Tjader belongs on the list, not only for his abundant talent, but for the distinctiveness of his sound. It’s fair to say, and truthful to say, that no other vibraphonist sounded/sounds quite like him.

Having started his jazz career as a drummer—most notably with fellow San Francisco State College student Dave Brubeck (documented on the Fantasy label’s albums: Dave Brubeck Octet, Dave Brubeck Trio Featuring Cal Tjader, and Distinctive Rhythm Instrumentals)—Tjader wasn’t known as a composer. Instead, he chose to perform mostly standards with graceful attention to the melodies and eloquent improvisational variations within the standards’ chord changes, rather than re-harmonizing them.

But even while working as George Shearing’s vibraphonist, Tjader, though ironically of Swedish ancestry, developed an interest in the complex percussiveness and incendiary excitement of Latin music. After hearing Latin artists like Chico O’Farrill, Tito Puente, and Mongo Santamaria, the possibilities of the vibraphone as a Latin instrument consumed Tjader. Similar to Dizzy Gillespie’s dedication to Latin music, Tjader recruited for his groups top-notch Latin musicians, instead of those already popular with the listening public.

Tjader’s approach worked.

After Tjader switched to Verve Records, his popularity rose, and so did his record’s sales. Selling over 100,000 units, his 1964 Soul Sauce album was a hit. Tjader’s invigorating sound throughout the sixties received much airplay due to the promotional strength of Verve, his collaboration with major jazz musicians, the more elaborate studio resources available to him, and the public’s growing enthusiasm for various forms of Latin music.

However, Tjader returned to Fantasy Records in the seventies and chose to enjoy suburban life with his family. And so, his performance schedule conformed to his lifestyle choices as he played mostly in venues in the Western United States, abandoning international tours and reducing his presence in the New York jazz scene.

Fortunately, Tjader performed at the Penthouse in Seattle in the sixties in parallel to the rise of his popularity. Fortunately, radio announcer and engineer Jim Wilke recorded his KING-FM broadcasts there. Fortunately, Zev Feldman, who has earned the sobriquet of “the jazz detective,” earlier had discovered Wilke’s cornucopia of professional-quality eight-track tapes recorded at the Penthouse. Feldman intended to share the widespread admiration for this singular talent on the vibraphone, awareness of which declined from the seventies until Tjader’s passing at the age of 56 on May 5, 1982. Fortunately, Feldman already had developed the resources to produce the newly available recordings of Tjader’s Penthouse engagements in elaborate, comprehensive, and respectful packaging.

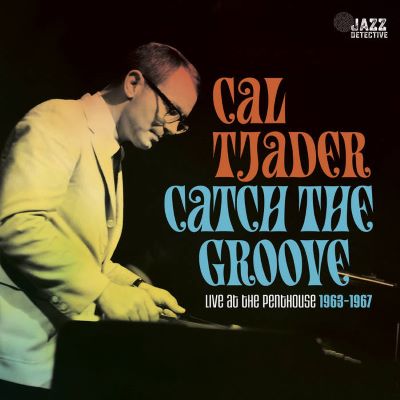

The result of such serendipity is the Jazz Detective label’s release, Catch the Groove: Live at the Penthouse 1963-1967. Its tracks document the growth of Tjader’s career during the Verve years. The recordings begin with pianist Clare Fischer in the 1963 performance and then move back to Lonnie Hewitt in 1965 and then to Al Zulaica in 1966.

Bass players included Fred Schreiber in 1963 to Terry Hilliard in 1965 and on to Monk Montgomery and Stan Gilbert in 1966.

Tjader’s drummers included Johnny Rae and Carl Burnett.

At the age of 22, master conguero Bill Fitch—who reportedly introduced Chick Corea, his roommate in New York, to Latin music—joined Tjader’s quintet for two years and recorded Tjader’s Soña Libré album. Cuban conguero Armando Peraza, who was on Tjader’s classic Soul Sauce album (and, yes, who was Carlos Santana’s percussionist), stayed with Tjader for six years after Fitch moved back to Connecticut.

In addition to his musical talent, Tjader possessed the ability to recognize and recruit musicians who shared his appreciation for the passion of Latin music—a natural appreciation that they felt and expressed, rather than analyzed. The personnel in each of his groups introduced their own arrangements that blended jazz, standards, and Latin genres.

One of those played in the 1963 Penthouse session was Fitch’s “Insight,” a composition of irrepressible clavé, pronounced percussive accents, and melodic flow. “Insight” may sound familiar to listeners, though they can’t put their finger on its title. Inexplicably, the track fades out after a little more than 2-1/2 minutes.

Peraza’s contribution, “Maramoor Mambo” (included in Soul Sauce), proceeds at a quickened pace and spreads sunshine all over the place, even within the shadowy nightclub. “Maramoor Mambo” features not only Hewitt’s vivacity with his solos and accompaniment, but also, naturally, Rae’s and Peraza’s invigorated mambo groove that no doubt invigorated the audience at the end of the 1965 set.

Hilliard’s “Pantano,” also from Soul Sauce, reinforces the unique Tjader sound, the vibes’ cool long tones contrasting with the rippling energy of Rae’s drum work and Peraza’s popping and pulsating conga rhythms.

Tjader recruited Fischer from his work as pianist and arranger for The Hi-Lo’s after their joint appearance at the 1959 Los Angeles Jazz Festival. Tjader had just recorded Fischer’s cha-cha-chá, “Morning,” on his Soul Burst album (which included Chick Corea on piano) before Tjader’s 1966 Penthouse appearance. Though, like Tjader, not of Latin ancestry, Fischer blended seamlessly into Tjader’s group due to their rapport for Latin music that started at Michigan State University, where Fischer met Latin students for the first time and where he minored in Spanish.

And of course, Tjader wrote some of the music performed at the club and which Jazz Detective captured for renewed enjoyment on Catch the Groove. The June 16, 1966, set includes his rumba, “Soul Burst,” from which his album received its title. Calmer and more fluid, Tjader’s “Fuji,” in blues form, features Gilbert’s initial rolling vamp over Tjader’s long tones before it breaks into walking-bass lines in four. “Davito”—more animated than “Fuji” but also kicked off by written bass lines, this time from Hilliard—provides the opportunity to multiple choruses of Tjader’s free impressions. With additional percussion from Peraza, “Leyte” sets up a more danceable rhythm than “Davito’s,” the repeats containing attention-getting, contrasting rhythmic pauses. Tjader gains improvisational intensity throughout “Leyte,” pianist Hewitt’s solo coming in almost as a release.

Catch the Groove signifies Tjader’s appreciation for his influences by including a relaxed version of Dave Brubeck’s “In Your Own Sweet Way,” which Tjader introduces with freely played prismatic ethereality over Schreiber’s pedal point. “Bags Groove,” with its signature sustains, second-chorus harmonies, and lead-in to multiple improvisational choruses, is Tjader’s musical tribute to Milt Jackson, the jazz icon who added the vibraphone to the instrumentation of bebop and to (as a member of the Modern Jazz Quartet) classically influenced music. Tjader recalls the invaluable contributions of Afro-Cuban pioneer Mario Bauzá when his group performs “Mambo Inn,” cleverly started by a dissonant-chorded teaser. The listener can hear the group, swept up by the irresistible groove, gaining momentum throughout the four-minute track, Zulaica’s interchange with Peraza particularly forceful and festive.

Possibly affected by the passing of Billy Strayhorn on May 31, the week before the quintet’s June 8, 1967, date, Tjader remembers the prolific composer by playing Strayhorn’s classic, “Lush Life”—quite a departure from the joie de vivre inspiring Tjader’s other songs. The verse consists of Gilbert’s mournful arco bass solo and Zulaica’s coruscating accompaniment without rhythm. Then Tjader joins in with poignant ringing vibrato and sustains at the chorus, Tjader’s two choruses of unchanging melody separated by one of improvisation.

Tjader’s move to Verve fortuitously introduced him to Creed Taylor, who had produced in 1962 the album that introduced the American public to bossa nova, Stan Getz’s Jazz Samba. And so, Tjader expanded his interests to Brazilian music as well. Tjader’s group that played Antonio Carlos Jobim’s “Mañha de Carnaval” at the Penthouse—consisting of Fischer, Schreiber, Rae and Fitch—had recorded that song just two days before on his Verve album, Soña Libré. Four years later, Tjader chose Jobim’s faster-paced samba, “O Morro Não Tem Vez,” for the Penthouse audience. Verve’s numerous contacts and larger budgets allowed Tjader to collaborate with a wider range of talent, including famous arranger and composer Claus Ogerman. Evidence of Tjader’s expanding group of influences showed up in his May 6, 1965 repertoire when his group played Ogerman’s “Sunset Boulevard,” the push of its vamp creating the jubilant energy that Tjader projected.

The abundance of tracks recorded at the Penthouse within Catch the Groove documents that Tjader combined his appreciation of Latin music’s soulfulness with his familiarity of popular songs like “The Shadow of Your Smile” or “Love for Sale.” His quintet’s calm but droll version of “On Green Dolphin Street” provides contrasts, particularly during Hewitt’s solo. His teasingly spare, seemingly off-handed, upper-treble improvisation of single notes alternates with the piano’s broad block chords at the repeats. And then, Tjader’s iridescent legato sustains of the notes offers yet another contrasting mood during one of the longest tracks in the album.

Feldman’s project to revitalize interest in Tjader’s music is diligently effective. Multiple interviews in the package’s 28-page booklet include those of: Tjader’s daughter Elizabeth on behalf of her and her brother Rob; surviving band members like Poncho Sanchez and Carl Burnett; family members of Tjader’s deceased sidemen such as Brent Fischer, Brian Montgomery, and Linda Zulaica; the son, Junior, of Penthouse owner Charlie Puzzo; Jim Wilke; Latin legend Eddie Palmieri; and jazz vibes legends Joe Locke, Gary Burton, and Terry Gibbs. Not to mention an insightful essay by Greg Casseus.

The inescapable conclusion from Catch the Groove’s recorded and printed documentation is that Cal Tjader was a jazz pioneer who approached music on his own terms.

He was a friendly band leader whom everyone liked. He was a devoted husband and father who made time for his family. And he enjoyed the pleasures of suburban living, such as a beautiful home and time for sailing.

Such happiness provides little material for a suffering-artist biography or melodramatic incidents that can’t be lived down.

Cal Tjader conveyed such happiness to his audiences, as Catch the Groove: Live at the Penthouse 1963-1967 verifies.

Label’s Web Site: www.thejazzdetective.com