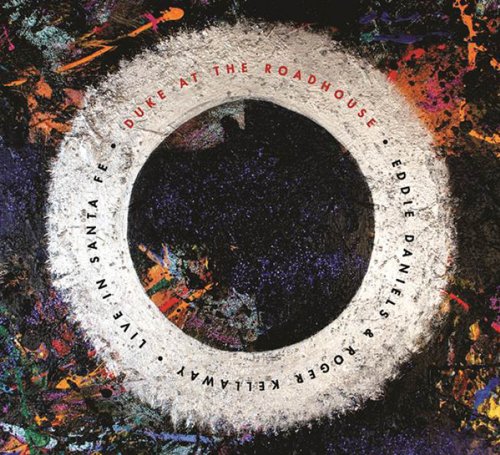

A virtual orchestral duo, Eddie Daniels and Roger Kellaway brought their consummate musicianship, the cumulative result of approximately one hundred years of combined experience, to raise funds for disabled children in 2012 in Santa Fe, New Mexico.

Why describe the concert as “orchestral,” besides the fact that Daniels and Kellaway can cover parts that other instruments, like trumpets and trombones, have played in jazz orchestra arrangements? The other reason is that they decided to perform a concert of Duke Ellington’s music. Without section arrangements. Without a rhythm section. Just piano and clarinet or saxophone. The lack of a band’s sometimes instrumental redundancy, or alternatively the lack of instrumental combined fullness of sound, challenges the audience not only to listen more intently to the music, but also to feel the silent pulse during the pauses. To imagine, or to remember, the Ellington orchestra’s harmonies when the soloists aren’t playing. Like numerous other jazz musicians who re-discover the delights of Ellington’s music, Daniels and Kellaway internalize it, adapting to their styles and personalities, making it reflections of their selves, as the songs nonetheless remain constant.

It appears that Daniels and Kellaway wrote arrangements of their own as they allow space for abundant improvisation throughout the recorded concert. The first song, “I’m Beginning to See the Light,” starts with a first chorus of Daniels playing melody and then a second of his improvisation backed by Kellaway’s almost imperceptible spare harmonies, until Kellaway’s roaring glissando cranks up the volume and the dynamism. One can’t help but notice the duo’s arranged unison lines and gentlemanly give-and-take of melodic parts. The same with the final piece, “It Don’t Mean a Thing,” which begins as a waltz with genteel, even eighth-note classical borrowings. Yet, after a switch into jazz territory, more Goodman than Ellington, the piece ends with pre-determined, playful, exceedingly difficult gales of notes. The fact that the first tornadic musical upsweep doesn’t end in unison as intended, Kellaway a fraction of a second behind Daniels, indicates the challenge of their performance and their fun in reaching to achieve it. As if giving themselves a second chance, not to mention adding a dramatic finish to the concert, Daniels and Kellaway repeat the written Goodmanesque unison sixteenth-note excitement and nail it the second time.

The chameleonic Kellaway adapts to every interpretation of Ellington’s music, employing styles from stride to blues to free jazz, as he injects unpredictability into every piece. While some of the song choices seem aligned with the instrumental traditions of Daniels’s instruments, like “Creole Love Song” on clarinet and “In a Mellow Tone” on tenor sax, Kellaway adapts instantaneously and flexibly to the feeling of the moment, as effective as a respectful medium-volume accompanist as he is as an intriguing, commanding soloist. An idea from Kellaway’s past recurs when cellist James Holland plays on four tracks, recalling Kellaway’s cello quartet from the early seventies. Holland broadens the colors presented by the now-a-trio with his cello’s sonorous bowed gracefulness of flowing harmonies. It’s when Holland steps out with confident, virtuosic solos, as during “In a Mellow Tone,” that his musicianship becomes evident, and the group’s interpretations attain additional dimensions. For instance, “Perdido’s” introduction proceeds with slower-than-expected trading of bars of melody among Daniels, Kellaway and Holland before the successive improvisations elucidate the stylistic differentiation among the three.

Daniels and Kellaway each wrote a composition for the occasion. Daniels’s “Duke at the Roadhouse” celebrates the concert with a light-hearted, floating tripleted theme that allows for plenty of improvisational space over the composition’s chords. Kellaway’s “Duke in Ojai,” a fanciful what-if title in itself, depends upon descending changes concluding in a punctuating six-note phrase, the intertwined musical lines as supreme as expected.

Two musicians applying lifetimes of ideas and accomplishments to a selection of Ellington’s songs, Eddie Daniels and Roger Kellaway individualize the music, command the instruments, generate engaging ideas, and affect the audience in the service of a worthy fund-raising project and of the delights afforded by the highest levels of jazz performance.