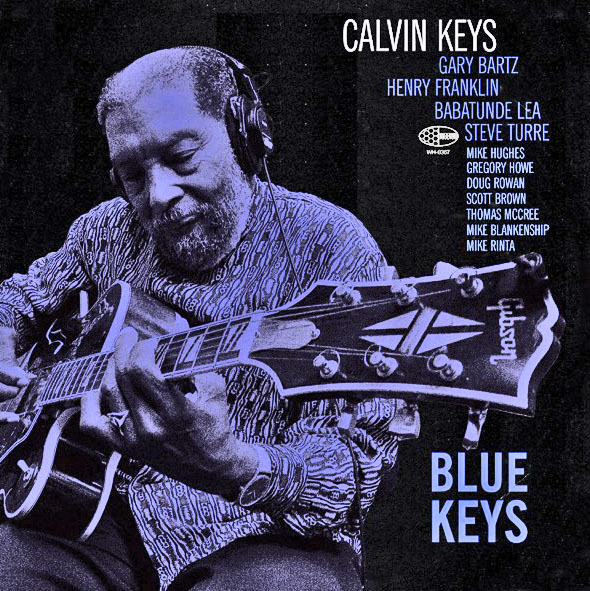

Calvin Keys celebrated his eightieth birthday in San Francisco’s Ruth Williams Memorial Theater in the Bayview Opera House on March 6, 2022. Due to concerns about the Omicron variant of COVID, the date of the concert was postponed for a month after Keys’s birthday on February 6, 1942. Thankfully, occur it did, though.

Consistent with his long-time generosity and his dedication to mentoring emerging talent, Keys donated the proceeds from the concert to the Opera House, whose mission is to assist at no charge local artists, as well as theatrical and studio technicians, to help them learn about lighting, video production, and sound control.

And…the event celebrated the release of Keys’s upcoming album, Blue Keys.

Recorded in 2018, Blue Keys is a reminder of Keys’s fluidity, soulfulness, individuality, and effortless technique. His recordings, starting with his classic Shawn Neeq in 1971, have been influential. So much so that Pat Metheny recorded his own composition, “Calvin’s Keys” on his 2008 Nonesuch album, Day Trip.

However, the sporadic timing of Keys’s releases has left listeners wishing for more—particularly those on the Bay Area, where Keys is respected as one of its musical legends.

Now, more is here.

Much more.

More of Keys’s friends appear on Blue Keys, including keyboardist/percussionist Gregory Howe (producer of Keys’s Detours into Unconscious Rhythms, 2001, and Electric Keys, 2013—and producer of, and Moog synthesizer player on, Vertical Clearance, 2006); bassist Henry Franklin (Proceed with Caution! 1974); percussionist/drummer Babtunde Lea (Vertical Clearance); drummer Thomas McCree (Electric Keys, and Vertical Clearance); saxophonist Doug Rowan (Electric Keys); and trombonist Mike Rinta (Electric Keys, Vertical Clearance).

More local musicians add to the brew, such as Mike Blankenship on piano, Scott Brown on bass, and Mike Hughes on drums.

There’s even more. Jazz masters Gary Bartz and Steve Turre [Turre being born in Omaha, as was Keys] provide their own unique voicings to the recordings too.

More of Keys’s original music, like “Ck 22” and “Bk 18,” appears on Blue Keys.

So does more of Keys’s compositional collaborations with long-time musical associates: Gregory Howe (“Six to Seven” and “Blue Keys”) and Henry Franklin (“Making Rain”).

Howe’s own contribution includes “Ajafika” (Keys’s given African name). Howe and Franklin worked together to write “Hundunit.”

The point being that the musicians performing on Blue Keys, some of them being Keys’s closest friends, have known, or worked with—and respected—him for decades.

They know Keys’s music. They know Keys’s personality. They know how to immerse themselves into the vibe that Keys sets up.

And they’re joining him to record more of his music and revive the distinctive, irresistible groove that Keys has been spreading for 63 years. Ever since, at the age of seventeen, Keys toured and recorded on the Jaguar label with saxophonist Little “Walkin’” Willie [Hickerson] and His Swinging Blues Men.

Graciously, Keys features each member of the band on “Peregrines Dive,” composed jointly by Keys, Howe, Blankenship, and Rinta. Opening with a one-minute rubato blending-of-sunrise-colors musical image, at first Blankenship establishes peacefully the minor-key, fully chorded harmonies. Then the individual voices of Keys, Bartz, and Turre come in for quiet, leisurely greetings. Awakened, their joy brightens when first, not Keys, but Bartz, and then Turre and then Keys solo over the pulsating drum work. This is the first Keys solo we hear on Blue Keys. With seasoned force, it emerges from an accompanying vamp to springy, effortless scalar lines and stirring force until it blends in again with the band’s counterpoints before the ending.

Then groove occurs on “Ck 22.” Trance occurs. Single-chorded modality occurs. Powerful, throbbing electric bass lines and Lea’s conga dance-inspiring patterns occur. Which explains the occasional observation that Keys’s interests are aligned with Afrobeat pioneers like Fela Kuti. Modest yet again, Keys, plucking and then ringing unchanging chords, at first elaborates upon the bass lines as he allows the piece to become a jammin’ highlife showcase for Turre’s both open and muted “talking” trombone and for his shells. As if responding to a request for an encore, the hypnotic vamp returns after Turre slows and softens to a teaser of an ending at 5:08. Keys’s masterful balance of textures elucidates his comprehensive sonic objective for the piece, while allowing for the freedom of expression within it.

“Ajafika,” which recalls Keys’s appellation from the Proceed with Caution! days, compensates for his submergence within his band on the Blue Keys’s first and second tracks. Another modal composition, “Ajafika” features Keys’s performance of acid-jazz-like phrasing over the texturalrhythm without harmonic backup. The repeated bass pedal point is sustained for 3-1/2 beats and cymbals reverberate over back beats,until the fadeout, as Keys continues playing. “At Arrival,” framed by a four-beat phrase alternating with a four-beat rest, provides the opportunity for Keys, Bartz, and Turre to trade solos, their sweetened harmonies modal again at a moderate swaying tempo that creates a relaxed unified mood.

“Making Rain” moves from trance and modality into a soulful 12-bar blues as Keys reminds the listener that he is one of the masters of the blues. Keys’s immersion into the emotions summoned by the music continues through successive ardent choruses as Franklin’s sturdy walking bass work anchors Keys’s solos, which are deep in the genre but nonetheless individualistic in a style and a tone that are Keys’s own.

“Six to Seven” adapts the blues to an off-kilter meter of 13/8, as the title implies. Rather than being a gimmick, the teaser of the eighth note added to the standard 6/8 rhythm provides an extra accent as the melody rises to the repeat of the vamp. The unconventional meter distracts not a bit from the piece’s infectious force, and it underlines Keys’s interest in exploring complex jazz concepts, as well as funk, R&B, and the blues.

Then the standard blues form happens again on “Blue Keys,” Turre, Bartz, and Howe provide the harmonic backup to Keys’s virtuosic interpretation, the culmination of his experiences in Ray Charles back-up band, as well as with legendary organ icons like Jimmy Smith, Dr. Lonnie Smith, Jack McDuff, and Groove Holmes.

Lea, a strong presence on congas, adds color to “Hudunit,” which consists mostly of a vamp played by Keys and Franklin. Like all the other tracks on Blue Keys, “Hudunit,” at 3:38 minutes, leaves the listener surprised at the track’s brevity and wanting more.

Yet, like the opening track, “Peregrines Dive,” the last track, “Bk 18,” is longer than those between them, as if giving the listener a final chance to appreciate what they have heard. Consisting of rhythmic build-up of intensity over another vamp, drummer McCree’s push breaks into the open when he solos too before the final slowdown and fadeout.

Artists’ Web Site: www.calvinkeysjazz.com

Label’s Web Site: www.widehive.com