Christian Howes is, and has always been, not just a jazz violinist, but also a jazz innovator who searches for inventive means of expression as he expands the potential for his instrument. Because that’s the nature of his intellect and his personality, Howes would be exploring new musical pathways even without recognition for his discoveries. His journey recalls that of other jazz musicians who never stop pushing the boundaries of their instruments, as—for example, in a purely musical realm rather than being confined to a jazz context—Gary Burton advanced from country-western to jazz to fusion to sonic inventions like his four-mallet technique to classical to, surprisingly, tango, even as he created inroads for jazz education at the Berklee College of Music. Howes’s journey has taken him from classical to gospel to rock to blues to electronics to jazz to music education to digital music production. And now Howes too, like Burton and also like Jane Bunnett, has adapted and incorporated Latin music into his distinctive mixture of musical interests. All of them, as they investigate innovative musical possibilities and search for passionate expression, have adapted their instruments and jazz sensibilities to the infinite variations possible within Latin music’s percussivensss and emotional honesty.

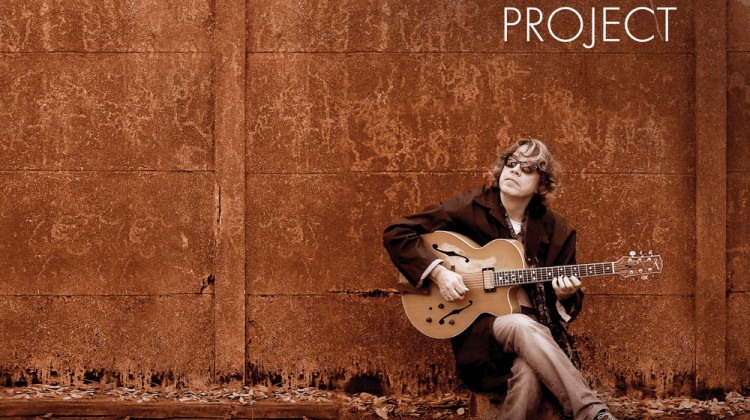

Howes’s southern exposure involves teaming with accordion virtuoso Richard Galliano, backed by a traditional trio of piano (Josh Nelson), bass (Scott Colley) and drums (Lewis Nash). Both Howes and Galliano contribute their own compositions, marking the project with their own personas in addition to the performances of works by composers like Astor Piazzolla and Ivan Lins. Nonetheless, the apparent effortlessness of the playing indicates mutual respect for the music, not to mention rippling mastery of their instruments. They explore pieces in which violin and accordion seem to be the necessary primary instruments, rather than joining a larger sound like that of an orchestra or rather than accompanying others. Howes and Galliano appear to be celebrating the multitude of opportunities.

Opening the album with Egberto Gismonti’s “Ta Boa, Santa?,” Howes lets the listener know what to expect throughout this Latin excursion: that is, flawless execution of prestissimo melodic exposition, fervent communication as the songs develop, complementary give and take as one responds to the other, unceasing percussive undercurrents, unexpected twists, elegant subtle flourishes like turns and mordents, extroverted reach to the audience, concurrence with the listener’s own pulse, and finally that satisfaction at the end of a performance that one has experienced something individual, inimitable and special. Even though the second track, Ivan Lins’s “Aparecida,” contains a sense of calmness in place of excitability and logical melodic flow in place of surprise, the salient characteristics of the entire album, the heartfelt release of emotions, remain intact. Ray Bryant’s “Cubano Chant,” though, does represent a pleasant surprise as arranged by Galliano, what with its surging pulsation on accordion and Howes’s soaring, jaw-dropping improvisation, not to mention Colley’s and Nash’s thrilling supporting percussive blanket.

Still, just as fascinating are the original pieces that the the pricipals contribute, proving their value as composers as well. Galliano’s “Heavy Tango,” with no holding back, incorporates the passion of the dance while appearing to take into consideration his and Howes’s technical excellence and Latinized soulfulness. The tune’s heavily accented lunges, ornamental trills, Argentinean classical references, chugging accordionistic surges, and fast-as-lightning unison and harmonic phrasing culminate in a literally smashing finish. Howes’s “Tango Doblado,” more courtly and mannered than Galliano’s tango—at least at first—incorporates initial changes of mood reminiscent of Howes’s earlier experimental and hilarious tune from his album Ten Yard, “Laughing Tango.” Too bad that that tango—with its oblique broken melodic chunks, wacky quotes, vertiginous sweep, blues influences, metrical teasing, stabbing dissonances and stringed risibility—wasn’t included on Southern Exposure. Then again, perhaps it doesn’t fit into Southern Exposure’s emphasis upon respectful interpretations of South and Central American subgenres.

While “Tango Doblado” refers to past influences leading up to the musical fulfillment represented by Southern Exposure, Howes’s “Gracias Por Ilustramos” indicates the present and the future as Howes assembled a virtual string section that participated digitally from across the United States and Europe. Howes has progressed to establish a file-sharing production service that allows him to collaborate with hundreds of students around the world, and Southern Exposure’s final track is the result. “Gracias Por Ilustramos” showcases not only Howes’s command of his instrument once more, but also his talents for compositions, arranging, producing, improvising, musician selection, digital mixing and comprehensive vision.

On Southern Exposure, Howes and Galliano play their instruments, infrequently heard in a jazz context, on unparalleled levels of feeling, imagination and technique throughout the album. There’s a word for what Howes and Galliano have created:

Beauty.

Artist’s Site: www.christianhowes.com

Label: Resonance Records