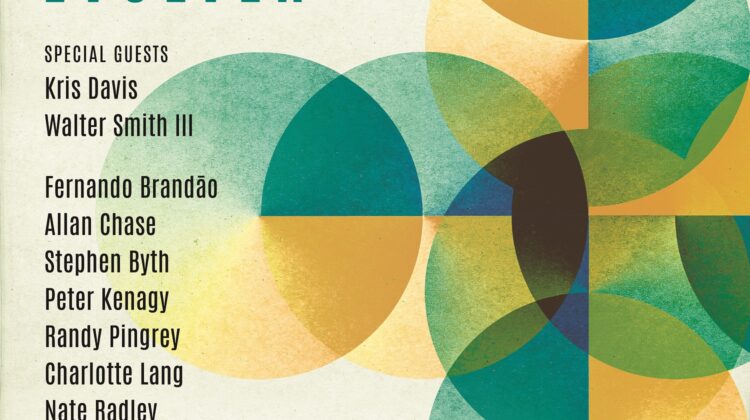

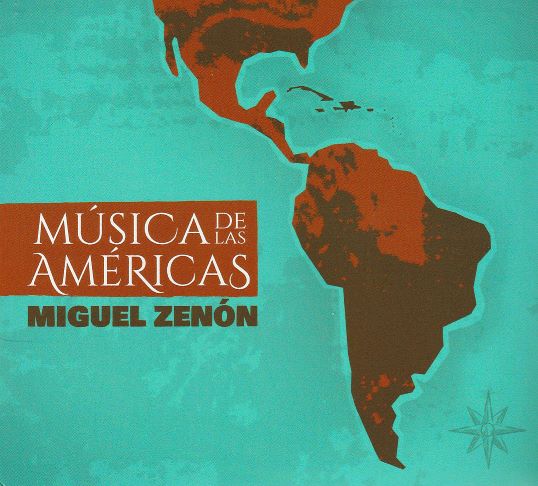

Significantly, the title of Miguel Zenón’s most recent album refers to more than one America.

The multiplicity of Americas summarizes the point that he wants to make through his music: There was, and still is, more than one America. Zenón’s album includes a track, “América, el Continente,” that describes the continent, rather than the country, of America.

But the continent of South America, or “the New World,” explored by navigator Amerigo (“Americus” in Latin) Vespucci, generated controversy within Europe due to doubts about the authenticity of his reports.

In his book, English Traits, Ralph Waldo Emerson wrote: “Strange, that the New World should have no better luck,—that broad America must wear the name of a thief. Amerigo Vespucci, whose highest naval rank was boatswain’s mate in an expedition that never sailed, managed in this lying world to supplant Columbus, and baptize half the earth with his own dishonest name.”

Yet, the popularity across Europe of Vespucci’s reports led to cartographers Matthias Ringmann and Martin Waldseemüller’s publication of a new world map in Introduction to Cosmography. Its introduction suggested naming the continent after Vespucci: “I see no reason why anyone could properly disapprove of a name derived from that of Amerigo, the discoverer, a man of sagacious genius. A suitable form would be ‘Amerige,’ meaning ‘Land of Amerigo,’ or ‘America,’ since Europe and Asia have received women’s names.” Vespucci’s discoveries were unquestioned, and unquestionable, after the publication of the Universal Geography According to the Tradition of Ptolemy and the Contributions of Amerigo Vespucci and Others. There was no turning back.

Thus, it seems that the New World’s continents may have been named after a self-promoter, or in the least an exaggerator, who used the power of the European press for the exponential increase in his name recognition, as noted by historian Felipe Fernandez-Armesto in his book Amerigo: The Man Who Gave His Name to America.

First of all, the Americas weren’t a “New World.” They already existed. They were already inhabited. And second, the lands of Indigenous inhabitants of continents previously undiscovered were named and defined by Europeans thousands of miles away, all but a handful of whom had never seen the continents.

Zenón’s concerns on Música de Las Américas involve the Americas before colonization and the results that remain.

Those are weighty subjects for one album. However, having lived in both Puerto Rico and New York City, Zenón, a recipient of both the MacArthur Fellowship and the Guggenheim Fellowship, is aware of the cultural diversity within the American continents. His impassioned concerns about historical truths, communicated through his exceptional technical abilities, allow him to describe his points, not only with incredible alacrity as if in ardent speech, but also with striking rhythmic and melodic inventiveness that captures the music of the cultures of his concerns.

“América, el Continente” begins as a thoughtful piece at a medium tempo, as well as in a medium volume, with Zenón’s soft two-note phrases in 6/8, flowing above pianist Luis Perdomo’s treble-clef pattern. Just as the listener expects the piece to be a calm meditation on the subject of the Americas’ identities, bassist Hans Glawischnig takes an extended solo that seems to be a continuation of the serene first section. Instead, the solo is a lead-in into a vibrant middle section at a faster tempo with Zenón and Perdomo’s subtle, and astounding, unison written performance of precision and clarity. After that, “América, el Continente” ends as it began, the composition revealing itself as an exercise in storytelling alternating between tranquillity and agitation.

The majority of Música de Las Américas investigates pre-colonial Latin America as Zenón’s composition vivifies the life forces of the two major Indigenous communities: the agricultural and nonviolent Taínos and the aggressive Caribes. “Taínos y Caribes” depicts their social contrasts with the rhythm section’s throbbing vamp under Zenón’s lightning-fast improvisation. Very few jazz groups could perform at this high a level of swirling virtuosity in the exposition of a theme. The group’s cohesion throughout the romp is but one example of the musical camaraderie created throughout the quartet’s years of performing together. No doubt, Zenón chose “Taínos y Caribes” to open the album as a rousing performance to capture immediate listener attention. He succeeded.

With “Navegando (Las Estrellas Nos Guían),” Zenón explores musically with a sense of admiration the ability of Indigenous seafarers, guided by stars, to navigate the seas through hand-made vessels. Such an image of gliding motion creates suggestions of smooth rhythms awaiting expression as music. The purity of Zenón’s alto sax sound over long tones, splashing eighth notes and the inevitable sixteenth notes, project joy in the piece’s major key. For further elaboration, the Puerto Rican plena group, Los Peneros de La Cresta, joins the jazz quartet at 5:34 with call-and-response lyrics and spoken word and the addition of panderos and percussion.

Zenón includes other musicians on some of the other tracks too, such as jazz percussionist Paoli Mejías deepening the intensity of “Opresión Y Revolución.” This composition recognizes struggles against oppression through various uprisings, especially the successful Haitian revolution for independence against French rule from 1794 to 1801. Built upon Perdomo’s repetitive adjacent two-note chord rising and falling in octaves, as well as Cole’s depiction of skirmishes (pop! boom!), the piece builds to Mejías’s exciting percussive conclusion, over which Zenón’s alto sax zings and sings.

Victor Emmanuelli introduces “Bámbula” on the barril de bomba, a Puerto Rican percussive instrument originally made from rum storage barrels and goatskin. Accelerating from his original percussive pattern, Glawischnig establishes the vamp that continues through the piece until the opposing long-toned bridge. Then the group re-creates the intensity of the Haitian dance of the track’s title, also named after the same type of drum. Zenón introduces “Bámbula’s” motive vertiginously, zigging and zagging and tossing in 64th-note phrases as if they’re afterthoughts. After Zenón, wailing in the altissimo range, and Perdomo, whose seemingly effortless treble notes glisten, exchange fours, the piece slows dramatically. Zenón restates the melody with deliberation accompanied only by Perdomo’s rubato accompaniment. And then the track ends with exhilaration before the fade.

Once again adding a musician appropriate for capturing the flavor of the piece, conga player Daniel Díaz embellishes “Antillano,” Zenón’s tribute to the Antilles: the islands thought to have been the location of the first fateful contact between European and Latin American Indigenous cultures. Lightly danceable and consistently jubilant throughout, “Antillano,” the album’s final track, emphasizes the celebrations that the music enhances or even makes possible, Díaz’s upbeat concluding solos at first are played at a moderate tempo and then faster and then back to a medium tempo again, jabbed by Zenón’s occasional accents.

Another of Zenón’s considerations about pre-colonial Latin America, expressed in “Imperios,” involves the insufficiently acknowledged intellectual advances of its cultures, including mathematics, astronomy, agriculture and more—which represent collections of their thoughtful solutions for various community, environmental, and organizational challenges. His quartet, thoughtful as well, slowly blossoms from a quiet, but hardly solemn, ten-quarter-note theme into a rapturous development in 10/4. The simplicity of the initially modest motive evolves into a sweeping, faster opportunity for the quartet’s glistening, rhapsodic improvisation. In contrast to Zenón’s solo in the first chorus in largo tempo, the gradual acceleration of the concluding phrase at 8:32 breaks into a remarkable finish of crackling rapidity. It’s all the more remarkable that Zenón and Perdomo perform the phrase at 200 mph in unison, cinematic in its vivacity, and proving once again the group’s extraordinary rapport.

While “Imperios” consists of a slow but, in the end, exciting build-up of tempo, “Venas Abiertas” presents a throbbing passionate musical statement from beginning to end. The musicians pull no punches about their opinions of the colonial empires’ exploitations of the continents’ natural resources to maximize wealth. Glawischnig thumping out the propulsive rhythms on low bass notes and Cole malleting rolls and textures, Perdomo accompanies, with broad minor-key chords and lines of eighth notes, Zenón’s fierce performance of keening assertions, altissimo points to be made, guttural overtones, and staccato punches of rising pitches.

From his early recordings on Branford Marsalis’s Rounder Records to his development as an distinctive jazz artist, Miguel Zenón continues to be consistent, yet surprising.

Consistent in his vision to explore the intricacies of Latin music—and particularly the music of his native Puerto Rico—and jazz (for his last album, Law Years, was a tribute to Ornette Coleman).

Surprising in, yet again, his exploration and presentation of another fascinating facet of music that’s not repetitious, but rather is unique to each album.

It’s anybody’s guess what will capture Miguel Zenón’s interest next.

Artists’ Web Site: www.miguelzenon.com