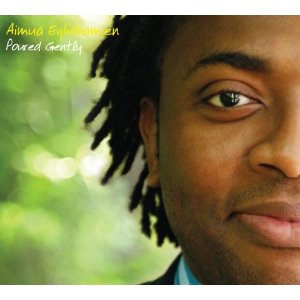

The success of a first album consists not just of a performer’s presentation of his personality, drawing attention from listeners with originality and spiritual kinship, but also of the work of collaborators who believe in the leader’s talent and enhance it with their own. Such is the case for British singer Aimua Eghobamien, who, yes, interprets songs with an intriguing voice, but who also records with four musicians who understand his artistic intentions. Eghobamien’s individualistic musical characteristics, to be immediately recognized as his own as he becomes better known by the public, involve a mixture of styles converging into a singular approach. Most prominent is Eghobamien’s careful attention to words as discrete elements to be investigated for their sound, meaning, continuity, vowel extensions, emotional evocation and usually soft vocal decay. Previously a student of mentors as disparate as Sheila Jordan and Mark Oswald, Eghobamien, by the evidence available on Poured Gently, appears to have absorbed their influences as well as a plentitude of others. On the one hand, Eghobamien evinces a jazz sensibility when, on “It Don’t Mean a Thing,” he indeed swings, not to mention inserting an element of funk, as he and his accompanists accelerate and then slow the tempo on a dime throughout this varied arrangement. However, the singer’s imprecatory introduction, of staccato stuttering piano notes and falling vocal pitch, serves notice that Eghobamien will interpret the song on his own terms. And, say, do I hear a twitter? A Monkish two-note dissonant twitter before bassist Ed Kollar starts the arrangement’s signifying vamp? Well, yes, it’s there. And appropriately enough, for sure.

Pianist Glafkos Kontemeniotis, whose respectful and shrewd accompaniments grace a growing list of singers’ albums, no doubt attained some of that musical insight from studies of Monk, as indicated on “Rhythm-A-Ning” (or “Listen to Monk,” as Eghobamien renames it). Defying expectations, though, Kontemeniotis backs the singer, not with punchy accents and quirky glissandi, but with rubato low-register rumblings and upper-keyboard plinks and rootless chords and suspenseful pauses. Eghobamien’s version of “Rhythm-A-Ning” is as unconventional as was Monk’s composition when it was new. Eghobamien’s theatrical studies combine spoken repetition of the lyrics, as if under constant consideration of meaning, and quarter-tone eeriness. The start of Poured Gently allows Kontemeniotis to establish the mood of “Estlin’s Dream,” more reverie than reveling, with a spare (dare I say beautiful?) presentation of melody on piano before Eghobamien comes in to sing words describing the feeling, voice and piano being in mutual haunting response.

As thoughtfully as Poured Gently begins, it just as reverently ends with “Benediction.” The song, a wish for security, peace and reassurance, is based on an Edo lullaby Eghobamien’s mother sang, and its English lyrics bookend the original Nigerian lyrics of “Jesu Oro Okakuomwen.” Unadorned by accompaniment and uncomplicated by progressive chord changes, the “Benediction” shares more with plainsong than jazz in its simplicity.

However, Eghobamien uses accompaniment for appropriate effect as the occasion warrants, especially on “Fascinating Rhythm,” which indeed is a celebgration of rhythms. Bashiri Johnson’s hand drumming sets up his own call and response patterns—not to mention irresistible rhythms—at varying pitches. Instead of a show tune presented as an exercise in syncopation, “Fascinating Rhythm” creates the occasion for cultural immersion in drumming, and Eghobamien’s emphasis on lyrics like “I get up with the sun” suggests natural connections between the fascinating rhythms of life and music.

The mutual understanding among Eghobamien’s performers, obviously one involving respect and canny appreciation of their potential contributions, is apparent in their approach to the music. Kontemeniotis’ arrangement of “A Child Is Born,” for example, takes into consideration the singer’s accustomed elongations of notes/words. Eghobamien wrings emotion from the song’s very first word, “Now,” as he swells and contracts its volume for effect before leading into the words that follow, “out of the light.” But note Kontemeniotis’ creative, minimalistic accompaniment, which in effect acknowledges his Bill Evans influence with its light two-note major ninth prods and rootless reharmonizations, even at the end of the chorus when resolution is expected. Such floating harmonies dovetail with Eghobamien’s toying with pitch, teasing the listener with suspense, never hinting at his melodic direction.

All of the selections of Poured Gently appear to have been selected carefully for numerous reasons, such as variety of styles, infinite moods and in the end a musical portrait of a singular singer, Aimua Eghobamien. His sympathy for the sojourner of “Migration” (“He waves farewell to his sky…. / To cities grey—lacking sky–… / Blurred faces pass—not an eye– / Nor a smile”); his expression of passionate artistic commitment and wisdom’s historical scope in “Passion Poured Gently”; and Eghobamien’s expansive sense of wonder and search for direction in “So Many Stars” add to a composite description that future albums will complete.

Year: 2010

Quaesitor Music

Artist Web Site: www.aimuaeghobamien.com