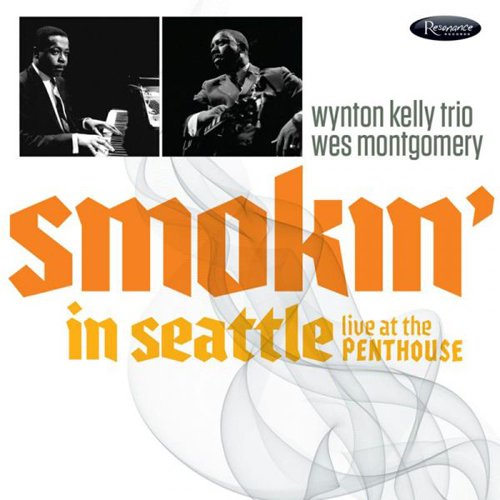

The excitement of contemporary jazz masters for the discovery of the tapes restored for Smokin’ in Seattle confirms the unique status that this new release has already attained.

Seattle radio announcer Jim Wilke recorded these 1966 sets of the Wynton Kelly Trio with the addition of Wes Montgomery at a venerable club there, the Penthouse. Strangely enough, the recordings weren’t released to the public until now. The reason is unclear. Perhaps no record producer was aware of the tapes’ existence, or maybe no producer expressed an interest in their commercial availability. Perhaps it was fate that these invaluable recordings weren’t marketed until now because Resonance Records turned out to be the perfect match of material and producer. It was worth the wait. Resonance Records executive producer George Klabin, who has been responsible for releasing numerous invaluable recordings, jumped on the opportunity to secure the rights to Wilke’s recordings, which are now available as Smokin’ in Seattle. As usual, Klabin and co-producer Zev Feldman have created a total package that such a recording deserves, including a booklet of rare photos, a close-listening review of the recording, comments of appreciation by jazz icons Kenny Barron and Pat Metheny, a historical account and engineering details from Wilke, and reminiscences by half of the album’s musicians from 51 years ago, Jimmy Cobb and Ron McClure.

Not only is this new album the worthy successor to the 1965 masterpiece, Smokin’ at the Half Note, but also it already received the enthusiastic praise from Barron and Metheny, who, one can assume from their liner notes, are thrilled by the Penthouse recording’s availability. Barron in particular notes Kelly’s unique sense of swing and detailed improvisation, one of many influences on his style. Metheny’s enthusiasm arises from the fact that he thought that Smokin’ at the Half Note, the most influential record in his musical development, was the only documentation of Montgomery’s playing with Kelly’s trio at the time. Now Metheny finds that another recording exists, and is available, for repeated close listening, bringing back memories of his attention to Montgomery’s style when Metheny was a youth.

The album, available on CD and vinyl and in digital format, consists of Wilke’s April 14 and 21 KING-FM broadcasts of his weekly half-hour show, Jazz from the Penthouse. In the cases of “Oleo” and “Blues in F,” the performances are cut short by a fadeout due to radio time constraints. In each segment, after Wilke’s spoken introductions, the sets start with the Wynton Kelly Trio, famed for backing Miles Davis before his second great quintet, as it performs two pieces before Wes Montgomery joins them for the final three. Shortly before this recording, bassist Ron McClure replaced Paul Chambers, McClure being a substitute several times before joining Kelly’s trio full-time from the Maynard Ferguson Band and before leaving to join Charles Lloyd’s quartet.

Starting with “There Is No Greater Love,” the trio surges ahead with exuberance and a sense of joy characteristic of Kelly’s playing. The irresistible pull of swing in Kelly’s style contrasts noticeably with Bill Evans’s on Kind of Blue. However, as the leader of his own trio, Kelly leverages his ability to draw an audience into his sphere. With successive improvisational elaborations without repetition from one chorus to the next, Kelly’s style is a combination of floridity and soulfulness that combines technically pleasing details with the blues.

Indeed, the next track, “Not a Tear,” offers suspenseful strolling blues that tells a story, complete with tremolos and stop-start anticipation, as it proceeds. The tight engagement of McClure and Cobb during the piece, especially as it moves into double time, provides evidence that this is a trio that already developed its own complete personality, even as Kelly receives less recognition than is his due because his numerous recordings as an accompanist.

When Montgomery joins the trio on “Jingles,” it’s like a handoff as the two of them play the fast melody in unison before Montgomery takes over with one of his blistering solos, complete with his unmistakable and influential phrasing that gained nationwide recognition with his popular recordings before he passed only two years later. The reaction from the audience was loud enough for the microphone to pick up whoo’s and ah’s from the electrified audience. The joyfulness of Kelly’s playing is especially suited to Montgomery’s infectiousness and ease of incomparable expression. Their reveling in the opportunities for performances with kindred spirits, even while creating technical feats appropriate to the moment of inspiration, may account for the veneration that jazz listeners attach to Smokin’ at the Half Note. And now that same veneration grows for the newly discovered radio broadcasts comprising Smokin’ in Seattle.

This Resonance album, a true discovery, immediately follows the start of Montgomery’s explosive commercial success from Goin’ out of My Head, as well as preceding Kelly’s gradual professional decline before passing from complications of epilepsy in 1971. Allowing for a comparison with their recording of the same song on Smokin’ at the Half Note, “What’s New” presents a Montgomery version that presages some of his slower recordings on later records such as his inimitable interpretations of “Georgia on My Mind” or “Yesterday.”

The second half of Smokin’ in Seattle is a reflection of the first, with two longer trio tracks, Blue Mitchell’s “Sir John” and “If You Could See Me Now,” of about the same length as those in the first half. Still admirable is Kelly’s sense of swing, not to mention the strength of McClure and Cobb in reinforcing it. Again, after those first two trio tracks, Montgomery comes in, this time with “West Coast Blues,” on which he accelerates the meter of three by playing rapid-fire triplets within each beat. Then, Antonio Carlos Jobim’s “O Morro Não Tem Vez,” (or “Somewhere in the Hills”), a medium-fast bossa nova, a genre popular at the time, offers some of Montgomery’s trademark chorded movements, use of octaves, unexpected glides, self-accompaniment and immaculate improvisational articulation while constantly referring to the melody. And then the second broadcast, and the album, end with two minutes of Montgomery soloing on and the trio accompanying him on Sonny Rollins’s “Oleo” before the final fadeout.

While it’s beneficial that jazz has advanced, absorbed new techniques and broadened its scope since 1966, Wes Montgomery and Wynton Kelly’s trio were doing those same things then as they set up new personalized possibilities for jazz expression that excite still today.

Fortunately, Resonance Records has revived that excitement with a recording that serves as a reminder of the unparalleled unique quality of these musicians’ work.

Label’s site: www.resonancerecords.org