Les McCann was a soul jazz phenomenon.

When he burst into the public’s consciousness in the early sixties, McCann’s ebullience and talent commanded attention—and inevitably contributed to having a good time. When he wasn’t touring (extensively), he was a continuing presence in the Los Angeles jazz scene. McCann recorded one album after another, on several labels: Liberty, Pacific Jazz, Limelight, Atlantic, Jam, A&M, ESC, Stone, 32 Jazz—and now, decades later, Resonance.

Les McCann is still a soul jazz phenomenon.

He has survived many of the jazz legends of his generation, even after the frequency of his recordings and tours slowed down after suffering a devastating strokein Celle, Germany in January, 1995.

The title of Resonance Records’s recent reminder of McCann’s gifts to audiences captures in a single phrase what people familiar with him already knew: There’s Never a Dull Moment!

Even today.

The album’s release helps celebrate Leslie Coleman McCann’s 88th birthday.

Though McCann initially played drums and sousaphone in Lexington, Kentucky’s Dunbar High School marching band, he found his calling when he starting to play piano in the Navy. When I interviewed him, McCann recalled, “My whole feeling of my music comes from my background from the South—from the blues, from the gospel, and from the church. That’s all we knew.” And so, McCann found that the piano provided a means for expressing how he felt. He continued, “When we feel something powerful, only music can help us let it out.”

McCann lets it out with undiminished vigor throughout Never a Dull Moment! Live from Coast to Coast 1966-1967.

Like every other release from Resonance Records, the copious accompanying booklet (in this case, comprising 32 pages) contains essays and thoughts from people who know and appreciate the artist. Producer and friend Pat Thomas writes, “A McCann concert often converted jazz fans into an expressive, shouting…, hand-clapping, gospel-feeling congregation.” And esteemed jazz pianists contribute a few thoughts. Monty Alexander: “Les…made people deliriously happy…. He greatly ROCKED THE HOUSE…. He IS one of the GIVERS, an aspect which is greatly evident in his playing.” Emmet Cohen: “Les McCann has always been about the people…. One of the hardest things to do, especially for a jazz musician, is to make people want to smile…, to come together, to dance and celebrate life.”

As the reputation of Les McCann Ltd. grew throughout the sixties, his spontaneous approach to gospel-derived jazz piano (“from the heart” is McCann’s self-description of his style in the album’s booklet) gained popularity as the recordings of other pianists like Ramsey Lewis, Gene Harris, Bobby Timmons, and Ray Bryant received airplay too. Recently, bassist Christian McBride’s “Car Wash” on his Live at the Village Vanguard album borrowed from the uplifting soul-jazz genre as the microphone deliberately picked up clapping hands and shouts and off-stage talking.

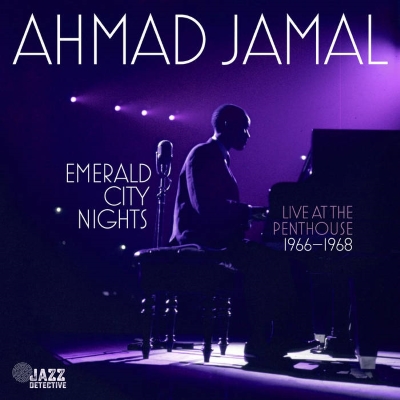

As determined and resourceful as ever—or perhaps even more so as their networks of contacts and momentum continue to grow—producers Zev Feldman and George Klabin discovered that a former Seattle radio announcer, Jim Wilke, still owned tapes of the McCann trio’s 1963 and 1966 performances at the Penthouse Jazz Club. In addition, Klabin fortunately had kept the tapes that he himself had recorded in 1967 of the McCann trio’s performance at the Village Vanguard in New York. Now, 56 years later, Klabin has included those Village Vanguard recordings when the perfect opportunity arose, that opportunity being the three-CD package of Never a Dull Moment! Live from Coast to Coast 1966-1967.

True to his reputation, there never is a dull moment in the package. McCann’s extroversion, unflagging energy, and selfless spirit continuously capture the attention of audiences. Wilke’s recordings of the performances for the Jazz After Hours radio program remain a valuable resource for the re-discovery of Les McCann’s irrepressible talent and influence.

Disk 1 commences with Dizzy Gillespie and Frank Paparelli’s “Blue ‘n’ Boogie.” The outstanding clarity of the sound restoration reveals bassist Stanley Gilbert’s supportive force and drummer Paul Humphrey’s instantaneous feel for McCann’s unpredictable technique, even as the pianist changes direction on a dime. For contrast, McCann follows up that medium-tempo blues with his own composition, the slow and soulful “Could Be.” McCann had just recorded the song with the Gerald Wilson Orchestra on McCann/Wilson. Arpeggios, thick block chords, expressive sustains, staggered triplets, and four-bar tremolos abound, as do lengthened rests that allow for Gilbert’s and Humphrey’s eloquent fills.

“The Grabber,” from Alexander’s live album, Alexander the Great, moves into more familiar McCann territory. It races with flawless crackling articulation throughout the piece’s stop-and-go-and-flow structure, infusing the audience with the trio’s until-now-contained characteristic might. The musicians perform with ease and confidence, even as McCann rat-a-tat-tats a repeated sixteenth note at prestissimo tempo.

“Yours Is My Heart Alone” defies expectations, as did “Could Be,” with its wordless eloquence, its slow tempo, and its resulting poignancy. The trio switches mid-song to a medium swing before McCann ends the performance by strumming the piano’s chorded strings. And then, the trio moves into an infectious groove enlivened by Humphrey’s second-line rhythm on “The Shampoo,” from the 1963 album, Les McCann Ltd. Plays the Shampoo at the Village Gate.

“Wait for It” follows, its soul-jazz mood set by McCann’s pedal point in the bass clef before it supports later his signature right-hand chords. Then he adds upper-treble improvisation over the minor-chord vamp that fades to the ending silence. The January 27, 1966, event ends with the trio’s invigorating interpretation of “This Could Be the Start of Something Big,” McCann drawing upon numerous elements of his talent to conclude memorably the engagement.

And that briefly describes the music on just the first CD in the package.

Disk 2 continues with more sets at the Penthouse Jazz Club, two of which were recorded in February 1966. As a bonus track, “Back Home Again in Indiana,” which features bassist Victor Gaskin and Bazley, was performed on August 15, 1963.

The second disc eases in as the volume rises on “Out in the Outhouse,” as if the enlivened and enlivening live version is caught mid-performance on February 3, 1966, before McCann introduces Gilbert and Humphrey to the audience. An even more lively choice follows: McCann’s interpretation of “A Night in Tunisia,” characterized at a faster tempo by the piano’s minor-key, lower bass-clef virtual stomp and driven again by Humphrey’s New Orleans-style celebratory drumming.

“Da-Da” starts with McCann’s two-note minor-key accents in modal form, like Miles Davis’s “So What’s.” Contrasting dynamically with the moderately restrained first 16 bars, McCann’s bridge energizes the sound even more with a wake-up! volume before the repeat. And then the trio takes off again in another engaging outreach to the audience. Humphrey’s stirring solos prodded by McCann’s two-note interjections relieve the exciting build-up of improvisational tension throughout the track.

McCann’s performances aren’t static. They always develop in intensity and bliss to end in a sunnier mood than that at the beginning. There’s never a dull moment, which means that McCann’s trio is always brilliant.

The second CD includes two pieces from the trio’s February 10, 1966, engagement at the Penthouse, when Tony Bazley substituted for Humphrey. “Lavande” begins slowly, Gilbert’s arco bass work portentous with somber foreshadowing as the first chorus reminds listeners of the early influence of gospel on McCann’s style. But as the spirit moves him, the mood of “Lavande” brightens considerably with each chorus. The performance moves from seriousness to an effortless light swing to an immersion in soulfulness, as if McCann’s happiness is always present in his playing, even when it’s not overt.

“There Will Never Be Another You” opens with a strolling largo tempo as McCann wrings romantic meaning from each note. As with his other interpretations, his performance tells a story, initially through rumination or spareness or intimation before progressing to unbounded joy. At 4:36, McCann expands from occasional framing accents into extended thrilling tremolos and block-chorded improvisation. The CD concludes with a hand-clapper of a jubilant bonus track from August 15, 1963: “Back Home in Indiana,” which features Gaskin’s chorus-long solo.

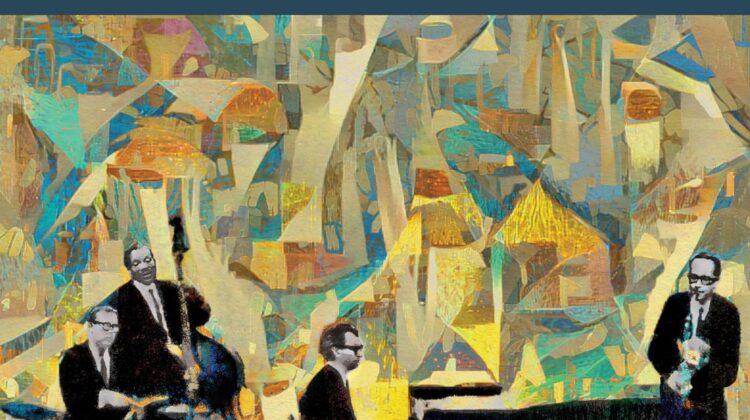

Disk 3 documents the McCann trio’s entire performance at the Village Vanguard on July 16, 1967. Bassist Leroy Vinnegar and drummer Frank Severino accompanied McCann. To remind jazz listeners of McCann’s talent, in 1998 producer Joel Dorn released the same set on a 32 Jazz album called How’s Your Mother? which inexplicably featured a cover photo of former vice president and presidential candidate Hubert Humphrey applauding McCann in front of an American flag. A generation later—exactly 25 years later, to be exact—as part of the Never a Dull Moment! Live from Coast to Coast 1966-1967 release to remind jazz listeners of McCann’s talent, Resonance Records producer Klabin includes in its entirely the trio’s Village Vanguard concert that he had recorded on his portable two-track tape recorder.

So, how was the mood of the New York audience?

Enraptured.

As always when Les McCann played.

“Love for Sale” develops from a funky repeated dotted-quarter-note-and-eighth-note vamp propelled by Vinnegar throughout the track, the vamp itself governing the development of the melody. “I Can Dig It” is a lightly swinging piece that features three choruses of Vinnegar’s authoritative bass work. Like Lou Donaldson’s “One Cylinder,” McCann’s “Doin’ That Thing” utilizes the form of a medium-tempo trance-like groove over a single chord, with quotes of “Wade in the Water” and “Goin’ out of My Head.” McCann’s solid groove on “Doin’ That Thing” confirms that McCann’s style advanced to encompass suggestions of that decade’s counter-cultural mood, rather than retaining an unchanged technique first heard on his 1959 Liberty Records album, Way Out Far, with the Lewis Sisters.

Indeed, McCann played at the Village Vanguard a short version of “Goin’ out of My Head,” its chorus relaxed and melodic before the increase in dynamic intensity during the song’s second part. McCann’s largo version of “Sunny,” also popular at that time, isn’t really sunny. Instead, except for the medium-tempo swing from 4:04 to 5:35, it consists of darker moods built slowly upon the Phrygian mode, as if in a reverent search for grace. This track confirms McCann’s understanding of the meaning of a song. Its oblique harmonic explorations create a different perspective. His enthralling tension of “Sunny” builds through the gradual hush-to-shout crescendi, flourishes of tremolos and staggering triplets until the release at 8:06. McCann plays his own solar-eclipsed rendition of “Sunny” as one else has played it. Who else could? McCann converts each standard to his own inimitable mood and style.

McCann’s trio finishes his rousing Village Vanguard show with “Blues 5.” His own timed blues improvisation—similar in intended temporal fit to Chopin’s “Minute Waltz”—clocks in at exactly five minutes. Transported by the overwhelming force of McCann’s performance, though, the audience no doubt lost track of time, though cleverly McCann didn’t. McCann’s trio ends the Village Vanguard event with his theme song, “The Shampoo,” bringing to bear the power of his gospel-influenced vitality.

McCann’s gift of joy to his audiences is part of his concept of “en-one-ment.”

But McCann’s “en-one-ment” involves more than music, as Monty Alexander, a recipient of generosity from THE GIVER, mentions.

Inspired by his belief in aesthetic and spiritual unity, McCann has used his influence to launch or assist the careers of others.

He recalled discovering some now-famous jazz talent:

- Monty Alexander: “I just went to Jamaica and heard him play. I talked my record company, Pacific Jazz, into bringing him out to California when he came to America.”

- Robert Flack: “Some of the people who lived in Washington D.C. called me and said, ‘You’ve got to hear this girl sing.’ Finally, I went in early the Monday before her gig’s opening and heard her [at Mister Henry’s]. I was so impressed that I flew back home, picked up my recording equipment and came back to record her myself. I talked to Atlantic, and they weren’t interested. They said, ‘We’ve got Aretha Franklin and a couple other people. We don’t need anybody else.’ I said, ‘Well, okay. I know some people over at Columbia too.’ Then they said, ‘Well, no. Bring her here first.’ Oh, I wasn’t kidding! But it worked.”

- Richard “Groove” Holmes: “I wrote a few songs for his first album. I realized that I was in the position to help a lot of people—great jazz musicians living in Los Angeles who weren’t being heard.”

- Joe Pass: “He was just out of prison. He was one of the greatest musicians on the West Coast, but no one would work with him. We agreed to make records together. It was like the simple and the great together, and it worked.”

Joe Alterman reminiscences as follows in the album’s booklet: “Because of Les…I’ve learned about the inter-connectedness of it all…. He told me, ‘The piano is just a tool. Without that piano, you would still be hearing music. You’ve got to hear what’s in you!”

In his interview with me, McCann shared these thoughts.

“Each one of us has the chance to discover something great about ourselves, no matter what we’ve done in the past. All of us have the opportunity to see God within ourselves. I discover it through everything I experience: people, painting, music. There’s no separation. It’s all one. I celebrate each day of en-one-ment.”

Artist’s Web Site: https://www.lesmccannunlimited.com

Label’s Web Site: www.resonance.org