The future of jazz composition, arranging, improvisation, and performance is in good hands.

A recurrent event in the jazz community is the preparation of eager young new talent to build upon the innovations of past generations.

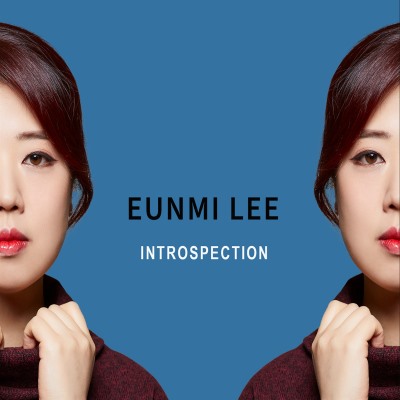

Yet another young jazz musician, Eunmi Lee, has arrived with intricate shaded colors, advanced textures, and thoughtful musical approaches. Her good hands are creating captivating piano improvisations and, just as importantly, write multi-cultural works based in the jazz tradition. The ideas that Lee’s hands express originate in her mind—a fact readily made clear by the title of her first album, Introspection, for which she composed all the music.

As Lee explains in her album’s liner notes, ruminations about her experiences, surroundings, and acquaintances inspire her music. Each track of Introspection results from her observations about aspects of human nature, such as compassion, egotism, tolerance, or “self-observation” (or, in other words, “introspection”).

Lee’s background that was formed from a multifarious breadth of experiences certainly leads to an original addition to the jazz genre. Even though she was born in South Korea and received her first degree, an associate degree in music, in Seoul, Lee has matriculated too in Holland and in the United States. As luck would have it, she moved to New York in 2020 at the start of the COVID epidemic. Despite that obstacle, her education culminated in a Master of Music Degree in Jazz Piano at New York University, where she met many influential musicians, none of whom was more influential than trombonist Alan Ferber, who produced Introspection and lined up the album’s musicians.

Though one would expect Lee’s approach to be that of world music, the first track on Introspection, “Gimmick,” proves that much of her music arises from the jazz idiom. Her inspiration for the composition was the various facades that people present to accomplish their intended impressions. Lee expands upon this idea when her sextet alternates discrete phrases throughout the piece from Dmin to C7. Those phrases seem to be intentionally conversational and quirky until the musical “talk” ends in a splash of broad dissonance and punchy eighth notes before the repeat. “Gimmick” moves on to a post-bop groove when tenor saxophonist John Ellis and Lee improvise over Matt Clohesy’s walking bass lines backed by Lee’s whole-note chords. Before the broad concluding sustained chord, drummer Ari Hoenig takes a solo elaborating upon the piece’s distinctive rhythms. It becomes immediately evident on the first track that Ferber made sure that Lee’s first album attained her vision with the contributions of some of New York’s first-call musicians. As one of her teachers, Ferber knew that Lee was ready for the high-quality production values that he arranged for her, for her singular compositions and authoritative piano performances are consistent with the high level of the musicians’ talent on the album.

As if to prove that she is not of one mind—that her music flows from her varied musical and cultural exposures— Lee wrote “Suspicion” as a chamber piece for strings, ethereal and wistful with unconventional atonal harmonies. In addition to Joyce Hammann’s violin, Lois Martin’s viola, and Jody Redhage’s cello, Lee mixed in with the traditional string trio’s sound Ellis’s bass clarinet and Vinicius Gomes’s guitar. “Suspicion” being the only piece on Introspection that doesn’t include her piano work, Lee’s haunting rhythmically free theme enters with the string trio’s legato harmonies until—each phrase being a distinct segment of its own—Gomes, backed by a single subdued notated pizzicato ascent, provides a solo reply as if in conversation with her. At 1:07, the spirit of the composition brightens with a quickened tempo and four march-like accented descending beats until a slight suggestion of a meter of three occurs at 1:31. Then, at 1:41, Gomes, Ellis, and Hammann repeat a connective phrase before the arrangement blossoms into its initial dark atonal richness again.

Lee’s “5:19” melds ideas from the cultures—Far Eastern, Brazilian, European, North American—that she has absorbed. Like the opposing yet finally complementary moods and musical techniques of “Gimmick” and “Suspicion,” “5:19,” even within the track’s five-and-a-half minutes, blends separate recognizable genres into a single composition. Commencing with Lee’s piano solo as she announces a slow reflective waltz, Ellis, backed by a string accompaniment, develops the poignant melody, as comforting as a lullaby. Until 1:33. Then “5:19” abruptly, without warning, moves into a brief medium-tempo samba, enlivened by Gomes’s comping, the samba’s melody still expressed by Ellis and the string ensemble. After a two-note accent at 2:06, the piece segues into a moving largo theme without the samba’s percussive rhythms.

Lee’s “Narcissism,” developed from her observations of the personalities, true or not, projected on social media, proceeds at a faster pace with a “Mission Impossible”-like five-four vamp. Clohesy, Hoenig, and Gomez stir up the track with light, cohesive vibrance. Essentially, the piece provides a platform ever rising in intensity for soloists Lee, Ferber, Gomez, and alto saxophonist Remy Le Boeuf before it concludes in a sustained effervescent improvisational blend.

Lee wrote “Mr. Weird” as a nod to big band jazz arrangements after she had a cinematic-like outer-body experience when she wondered about strange people think when they observe her, the ultimate consideration in pensiveness, if not self-consciousness. Whatever they may be thinking, Lee reveals her talents as a big-band arranger as she arranges a piece with an octet’s broad colors from Ferber’s lower bass-clef foundation to Tony Kadleck’s bright trumpet work. With forceful accents, Clohesy’s walking bass lines, and succinct light-hearted improvisations like saxophonist Jon Gordon’s, the just-under-five-minutes “Mr. Weird” wryly entertains the listener without overstaying it welcome.

An expression of compassion, “Wavelength” describes Lee’s discoveries—especially during the COVID quarantines—that people all over the world can understand one another and communicate, particularly through music, no matter the differences in cultures. How to compose a piece about such a connective emotion—powerful, delicate, and unfortunately rare? Lee wrote for her quintet a deliberately slow jazz waltz—this time shimmering, coruscating, dissonant, and rootless—consisting of sometimes Gomez’s wavering notes and sometimes Lee’s notes that are allowed to ring and fade as they stretch over several bars, thereby allowing for contemplation.

Lee ends her album with “Azure”—as in the color, blue. Not as in the blues. But as in the sky. For she thinks of her heart’s color as being, not red, as it appears to the eye, but blue, as it appears in her mind. For she believes the heart can offer hope and reflect the sky as a motivation for improvement. Accordingly, “Azure,” with a medium-tempo majesty, reflects Lee’s idea of writing a melody on the piano’s white keys, its optimism expressed by its structure based on the tonic. Indeed, “Azure” was written in C major, even though Lee arranges for the tentet to veer into harmonic detours before settling back to a straightforward major chord.

The multiplicity of influences implicit in Introspection suggests that Lee may share much more music of even more diverse styles and from other complexities within her inner visions.

Artist’s Web Site: www.eunmileemusic.com