How did the Blue Note record label’s most recorded musician fall into near-obscurity without a recording contract a decade later? Or just as intriguing is what he did to regain his popularity.

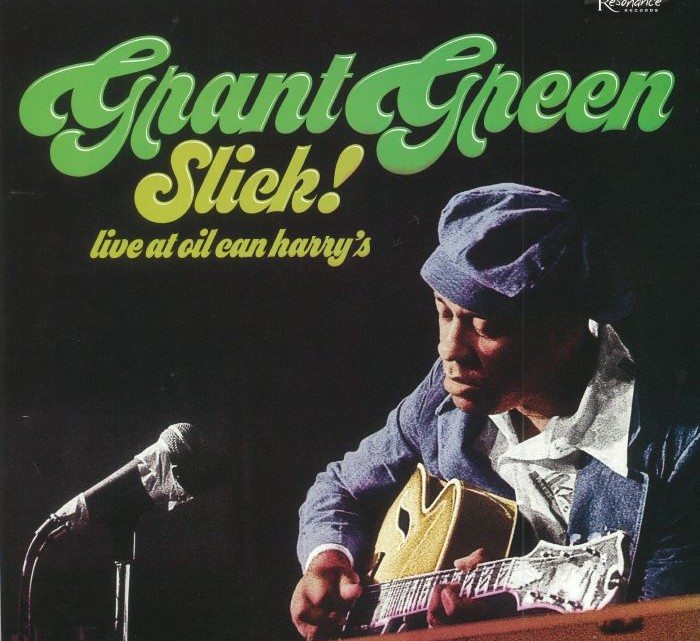

Resonance Records did it again! That intrepid label has discovered more obscure recordings, tucked away and almost forgotten for decades, but hidden in plain sight. These raw recordings, unknown until now to but a few, expand not only the discography, but also the understanding, of admired, or even revered, jazz musicians. As always, the label’s multiple producers lavished respectful attention on an artist, Grant Green, whose unrecorded revelations hadn’t been available to the public. Perhaps coincidentally, enterprising Resonance Records producer Zev Feldman uncovered not one, but two, extended, previously unreleased live concerts by Grant Green. As an indication of his dedication to Green’s work, Feldman tracked down recordings that were continents apart.

These recordings are important discoveries in themselves as they provide more musical ideas for Grant Green’s enthusiasts. But just as important is the fact that Funk in France and Slick! Live at Oil Can Harry’s uncover a later phase of Green’s career that previously hadn’t been documented. Those who absorbed Green’s recordings know of his work with his Hammond B-3 blues trios, his trio with Larry Young and Elvin Jones, his quartet with Sonny Clark, and his recordings with numerous Blue Note musicians like Herbie Hancock, Ike Quebec, Joe Henderson and Hank Mobley. It seemed that Blue Note released Green’s recordings, either as a leader or an accompanist, on an ongoing basis in the early sixties. Even more of those recordings weren’t released until more than a decade had passed. Yet, Green’s prolific career came to a sudden stop in 1967 when he moved to Detroit, where he performed locally but had no access to Blue Note’s recording opportunities, apparently intentionally so. Blue Note moved on; so did Green.

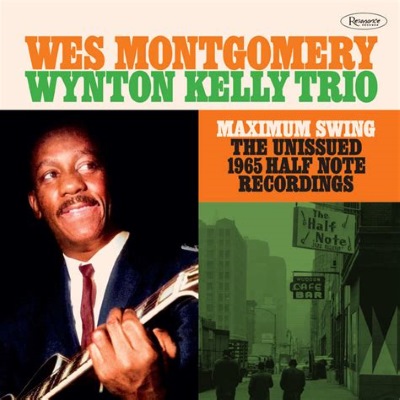

However, the music world had taken keen notice before Green’s absence from recorded music. Green’s voice-like, single-string lines, originating in bebop and seamlessly adapting to hard bop and ballads as his recording opportunities required, received allusions in other musicians’ recordings. Various younger musicians recognized the possibilities for expansion of a single possibilities-laden Green idea into an entire groove that they sampled. Accordingly, numerous popular musicians regard the individualistic Green as one of the most important jazz guitarists, along with Charlie Christian, Les Paul, Jimi Hendrix, Wes Montgomery, John McLaughlin, Kenny Burrell and Pat Metheny. One of Green’s admirers is guitarist Eric Krasno of Soulive, whose interview in the booklet included with Funk in France notes that “any guitar player I know understands the importance of what Grant does.” Krasno notes that “To me [Green is] like a Miles Davis figure of guitar.” That insight underlines the importance of the two new Grant Green albums on Resonance. For like Davis, Green moved on and adapted to new sounds available to the unexplored development of jazz. The difference between Davis and Green, though, is that Davis’s progression of stylistic development as he moved into modal jazz and fusion was widely known and sometimes wildly controversial; Green’s movement into funk was hardly known.

Funk in France and Slick! Live at Oil Can Harry’s remedy that unintended neglect.

By the time that Green signed again with Blue Note in 1969, he had incorporated rock music’s sounds into his own style. The result was a funk-oriented approach that remained constant in his performances afterward, though references to earlier interests, such as Charlie Parker-inspired bebop, gospel and Latin music, remained. Green’s emphasis on these newly released albums consisted of mostly improvisations at concert-driven lengths. Without the restrictions of a studio recording, Green’s funk groups roused audiences to ever-rising levels of involvement.

Funk in France is an example of Green’s transition from a studio’s management of recordings to the freedom of long-form concert performances. This two-album package begins with Green’s recordings in Paris’s Studio 104 at La Maison de la Radio. His studio performances there indeed include tracks of four to seven minutes each in a controlled recording environment. Green’s first album after returning to Blue Note was recorded just before this French Studio 104 recording. One of the tracks eventually turned up on YouTube, providing Feldman his clue to additional Green recordings held by Christiane Lemire and Pascal Rozat of Institut national de l’audiovisuel. While Green enjoyed the opportunity to record in the relatively new round Studio 104, an architectural marvel on the banks of the Seine, his recordings there, professionally recorded and filmed for French television before migrating to YouTube, adhered to the sound of his earlier Blue Note recordings. Green entertained the studio audience with the traditional backup of acoustic bass (Larry Ridley) and drums (Don Lamond) as he revisited his excellence in interpreting Sonny Rollins tunes, bossa nova, blues and intimations of funk. Barney Kessel joined Green on a masterful and gracious seven-minute appreciation of the French audience with Charles Trenet’s “I Wish You Love.”

Feldman’s conversations with Lemire and Rozat, however, led to his discovery in their archives of the Green’s new band that he took to the 1970 Festival international de jazz d’Antibes Juan-les-Pins on the Riviera. Freed of time constraints and the audience expectations of the studio audience, Green’s quartet played with abandon and intensity on July 18 and 20 for two segments at lengths between fifteen and thirty minutes. Ironically, the extended lengths of Green’s performances, not controlled by the standards of radio or television production, caused his appearances to be cut from a French TV broadcast. Instead, the audio recordings remain, and they were restored by George Klabin and Fran Gala to present-day digital standards. In contrast to the relative refinement of the Studio 104 concert, Green’s work at Antibes delved entirely into funk. The musicians he chose for his band reflected that interest. Tenor saxophonist Claude Bartee contributed to the quartet an aggressive, raw force, similar to the extroversion of David “Fathead” Newman,” that no doubt energized and received energy from the other members of Green’s group. Drummer Billy Wilson apparently was the second choice after Idris Muhammad for the tour, but Wilson nonetheless provided his own levels of deepening immersion in the music as the fiery concerts continued. Clarence Palmer, a veteran of other jazz recordings such as George Benson’s, heightened the funk with his insistent, simmering intense organ groove. In addition, Palmer’s interview in the lavish 48-page Resonance booklet is in several ways the most candid with his unvarnished truths about the recording industry. These include his opinions about the pressure for late-sixties jazz musicians to incorporate rock music into their repertoires. (An additional interview with B-3 jazz organist Dr. Lonnie Smith appears in the booklet as well, even though Smith doesn’t perform on the recordings—evidence of the Resonance dedication to thoroughness.)

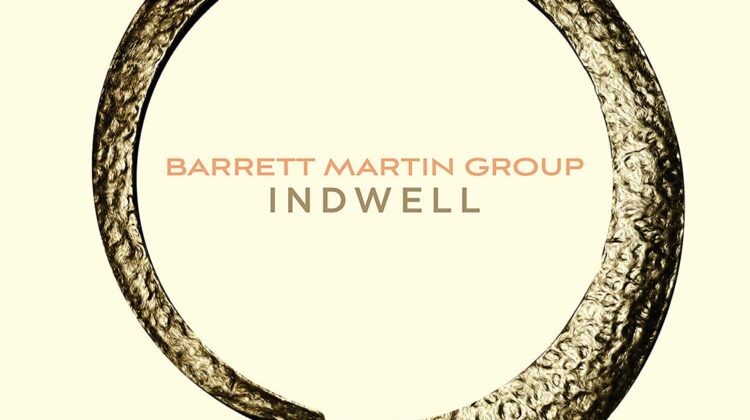

Thoroughness: That indeed is what Resonance consistently delivers in its respect for the music it recovers. Serendipitously, a conversation that Feldman happened to have with Gary Barclay, a Vancouver DJ, during a speaking engagement in 2016 led to the Feldman’s awareness of Green’s last recording. That recording occurred in September, 1975 at Oil Can Harry’s, a jazz club where local radio station CHQM-FM broadcasted. A concise retrospective of Green’s journey, the Slick! Live at Oil Can Harry’s album starts with “Now’s the Time,” Green’s tribute to his early inspiration, Charlie Parker. Green moves on to a 26-minute interpretation again of “How Insensitive (Insensatez),” which appears on the first Funk in France CD. But the track that galvanized Feldman was Green’s movement into a half-hour funk medley consisting of Stanley Clarke’s “Vulcan Princess,” the Ohio Players’s “Skin Tight,” Marvin Gaye’s “Trouble Man,” Bobby Womack’s “Woman’s Gotta Have It,” Stevie Wonder’s “Boogie On Reggae Woman” and the O’Jay’s “For the Love of Money.” This was a Grant Green that few had heard on recorded material. Joining Green in Vancouver were Emmanuel Riggins (father of Karriem Riggins) on electric piano, Ronnie Ware on bass, Greg “Vibrations” Williams on drums and Gerald Izzard on percussion. Even though numerous Green albums on Blue Note were released years after their original recording dates, perhaps it is fitting that the album of Green’s final music, Live at Oil Can Harry’s, remained unproduced until the eminently respectful producers of Resonance Records were able to release it.

Though less widely known now than other jazz musicians of his generation, Green nonetheless remains one of its most influential.

Recognizing Green’s importance, Resonance Records has, as always, created recording packages worthy of his stature. Each of the two albums, Funk in France and Slick! Live at Oil Can Harry’s includes comprehensive interviews adding to the understanding of Green’s artistry and a description of his life. None are more significant than those of his sons, Greg Green and Grant Green, Jr. The albums’ booklets include as well photographs of Green’s engagements in Canada and France, producers’ notes and magazine articles.

And for the first time, Resonance has taken on the responsibility of being a tribute band and concert promoter. The Grant Green Evolution of Funk Band includes guitarist Grant Green Jr., saxophonist Donald Harrison, keyboardist Marc Cary and drummer Mike Clark. Spreading the music of Grant Green, the tribute band will perform the music from both of the Resonance albums throughout the rest of the year.

A major undertaking, Resonance Recording’s sponsorship of Grant Green’s music makes 2018 a year of celebration for the funkiness of the jazz icon.

Label: www.resonancerecords.org