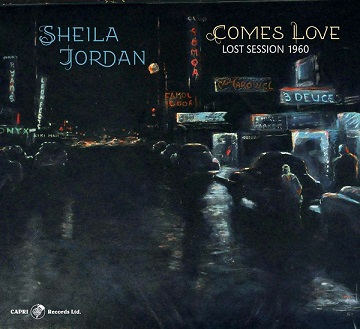

A rare and significant find this is!

Who knew that jazz legend Sheila Jordan was recording under her own name before her breakthrough Blue Note album, Portrait of Sheila?

Having escaped her childhood poverty in Johnstown, Pennsylvania, where she lived in a home without plumbing with seven uncles—Harry, Earl, Delbert, Bunky, Jackie, Esther (one seven years younger and another a year older than she)—and her grandparents while her divorced mother worked in a wartime factory in Detroit, Jordan, through innate, unique talent and sheer perseverance and love of jazz, moved on, first to Detroit and then to New York, to be one of the beloved, uncompromising, charming and enduring singers of the genre.

Feeling unsafe due to racial prejudice in Detroit while she was singing with other upcoming jazz legends like Frank Foster, Tommy Flanagan and Kenny Burrell, Jordan moved to New York in 1952. She remembers, “I left Detroit to get away from all of the prejudice, and then I got beat up on the street in New York for being with two Black painters.”

But Jordan’s influence from Charlie Parker at the Greystone Ballroom in Detroit and then again as neighbors in New York instilled in her the jazz spirit, specifically bebop. She continued to absorb the music and expand her contacts in New York until she recorded first with bassist Peter Ind—and then, as it now becomes known, her first album, the 34-minute Comes Love.

Albuquerque record collectors Jeremy Sloan and Hadley Kenslow discovered Jordan’s lost album while visiting record shops in New York. They contacted Capri Records’ owner Tom Burns, who ultimately made available the digitally enhanced release, thereby adding an invaluable new album to the Jordan’s discography.

Comes Love: Lost Session 1960 presents Jordan as a young singer with advanced talent sounding even younger than she does on 1962’s Portrait of Sheila. Her choices of songs, even then, were individualistic as she combined then-obscure pieces like “Ballad of the Sad Young Men” with covers like “They Can’t Take That Away From Me” (paying tribute to her childhood influence, Fred Astaire, who sang this song about intangible values [which Jordan understands all too well] in Shall We Dance). (Jordan said: “I walked two miles [in Johnstown] to go to all of his movies. Two miles down and two miles back. I loved his music.”)

A highlight of Jordan’s later concerts are her narratives in song of her life, usually accompanied solely by bass. One wonders if some of the songs of Comes Love reflect her experiences until the 1960 release of Comes Love. Jordan’s uncles were all hard-drinking coal miners: thus, “The Ballad of the Sad Young Men?” Her adolescent love of jazz in Detroit: “It Don’t Mean a Thing If It Ain’t Got That Swing?” The ups and downs from poverty to renown; the early acclaim of Portrait of Sheila followed by, to pay the bills, twenty years of anonymity as a secretary at the Doyle Dane Bernbach advertising agency, where she sang on commercials for Whirlpool refrigerators and Thom McAn shoes: “Glad To Be Unhappy?”

From the first phrase of the verse of “I’m the Girl,” the first track of Comes Love, Jordan’s voice is identifiable, though with a younger singer’s timbre. As in her later albums, she favored songs with a narrative that she can deliver with authentic feeling, from the set-up of the verse to the story’s conclusion on the ninth tone. (Additional examples of her narrative-based songs being “Ballad of the Sad Young Men” and “Don’t Explain.”) Jordan holds out the sustained notes of “I’m the Girl” for full value. Her descending phrasing emphasizes the appropriate emotions of the lyrics.

Jordan doesn’t remember who accompanied her on the album, but the back-up trio is first rate, the pianist comping with sensitivity in sync with Jordan’s voice and the bassist moving the songs along with choice half notes and buoyancy.

Her bebop chops are precise, and her joy is invigorating on her 1-1/2-minute version of “It Don’t Mean a Thing If It Ain’t Got That Swing.” In fact, her scatting confirms that her later works were based on her early technique, as represented on this version.

It appears that Jordan sequenced the songs to provide contrasts. The jaunty informality of “Comes Love” (“nothin’ can be done”) with Jordan’s trills and intervallic leaps and falls precedes Billie Holiday’s heartbreak of a song, “Don’t Explain.” And then, “Don’t Explain” precedes Harold Arlen’s “Sleeping Bee,” again complete with the rubato beginning verse explaining the situation before the bassist’s vamp interjects the vigor and happiness that Jordan transmits as she improvises the springy melody. She ends “Sleeping Bee” again, as does “I’m the Girl,” with a thoughtful sustain of the ninth tone. “Sleeping Bee” precedes “When the World Was Young,” as her matured wisdom looks back at earlier innocence, for which Jordan provides lyrical reminiscence with a voice in the middle register, except when she descends chromatically. Inventively, she concludes that song, emphasizing the word “young” with quarter-tone climb in her upper register. Then, “When the World Was Young” precedes a fast swinging version of “I’ll Take Romance.” Et cetera.

Even though, now that she’s 92 years of age, Jordan doesn’t remember this recording session, it’s obvious from the care that she infused in her singing, with unique characteristics that remain identifiable even now, that she took her singing very serious.

Because music is in her soul.

Sheila Jordan concluded my interview with her by saying:

“When I was a kid, there was no place to go to learn this music. You learned it from the records—the 78’s, if you were lucky enough to even own a phonograph. A lot of times, I wasn’t that lucky. I had to really fight to learn this music. I had to get beaten up on the street by people who hated to see the races mix. I had to learn the music as quickly as I could, any way that I could learn it. You know, I went to bed with this music in my head at night. When I got up in the morning, the jazz was with me all day long. I breathed, I ate, I lived this music every day. That’s dedication. What matters is that you’ve got the jazz in your soul. It’s with you all of the time, and it never leaves you. That’s the important thing.”

Label: www.caprirecords.com