Ordinarily, I don’t use words to describe a musician’s physical appearance. My assignment is to describe the elements and the quality of the universally inspiring art form of music, the potentially eternal purity of which exists at a level higher than the finite characteristics of the human body.

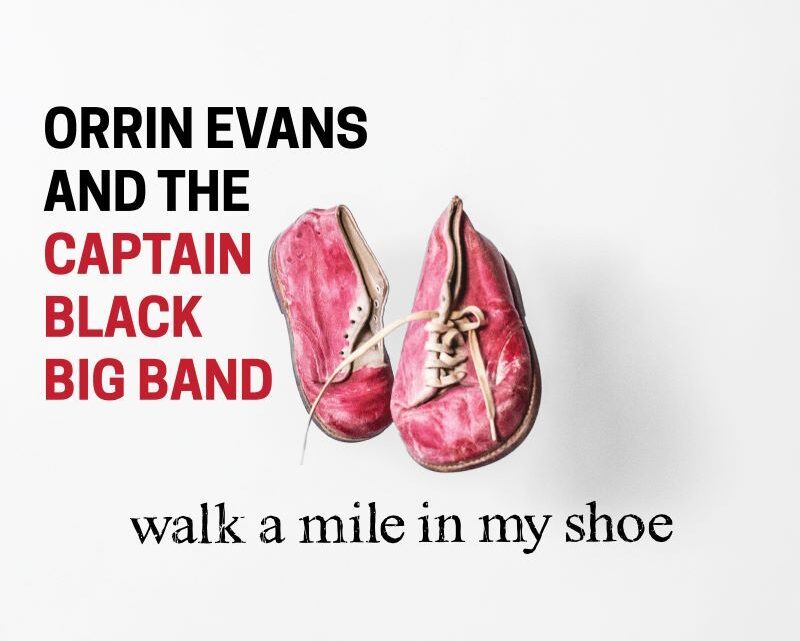

However, Orrin Evans presents his physical condition in both the title of and the image illustrating the cover of his most recent album.

The title, Walk a Mile in My Shoe, issues an imaginative challenge to listeners so that they can understand the distances that Evans has traveled, both literally and figuratively.

The cover image of the album consists of a pair of his childhood shoes. one of them was custom-made to adapt to his foot’s deformation resulting from neurofibromatosis. Evans has adapted. He still uses a cane. But Evans make his medical condition a symbol of his undeterred perseverance, accelerated artistic growth, perfectionism, and his attainment of self-confidence.

Evans says, “My musical journey is closely connected to my medical journey, and this record is me opening the door into what I’ve lived with for years.”

Not that jazz enthusiasts ever noticed any need for Evans to gain confidence in his artistry.

Prolifically releasing albums since 1995, Evans has developed an impressive discography, through which he has addressed personally important themes such as faith, bravery, injustice, overdue recognition (for Sam Langford, as an example), beauty, self-improvement, and freedom.

In addition, Evans has recorded with some of his respected contemporaries, including Ralph Peterson, Oliver Lake, Buster Williams, Wallace Roney, Bill Stewart, Antonio Hart, and Ambrose Akinmusire.

Seven of his albums were recorded at Smoke Jazz Club in New York. In addition, he has produced albums on his own label, Imani Records.

With such weighty issues pondered in past albums, it’s a surprise, and a pleasure, to hear that Walk a Mile in My Shoe on Imani Records elicits not contemplation, but uninhibited joy.

Three components combine to create the success of the album: (1) a big band, (2) singers, and (3) community (or The Village, as Evans calls those who support his music).

Walk a Mile in My Shoe is the fifth album recorded by Evans’s Captain Black Big Band, named in 1997 after the tobacco that his father smoked.

The arrangers—David Gibson, Josh Lawrence, Marc Stasio, and Todd Bashore—adapted the songs to highlight the force of the 12-piece band and the musical individuality of its members.

Unlike on previous Captain Black Big Band albums, though, the arrangements integrate the lyrics sung by featured vocalists into seven of the nine tracks.

Evans brings together musicians and vocalists who share the chemistry of their established relationships to celebrate the jazz community of Philadelphia—the hometown of jazz icons like Billie Holiday, the Barrons, Christian McBride, the Heaths, McCoy Tyner, the DeFrancescos, Benny Golson, the Eubanks, Ray Bryant, Mickey Roker, Kurt Rosenwinkel, Shirley Scott, Paul Motian, Grover Washington, Jr., Questlove, Pat Martino, and many others.

The hometown of the singers on Walk a Mile in My Shoe—Bilal, Joanna Pascale, and Paul Jost—happens to be Philadelphia too.

Bilal Oliver delivers an emotional performance of his own song, “All That I Am,” whose arrangement by Gibson emphasizes emotional depth with the band’s accompaniment. The concluding solo by guest artist Nicholas Payton expresses the baring-the-soul sentiment through a broad tonal range, as does Bilal. With similar passion and concern for the future, the vocalist also performs “Save the Children” from Marvin Gaye’s What’s Going On album (not to be confused with Gil Scott-Heron’s composition of the same name). Enhanced by the soulful addition of organist Jesse Fischer’s at the words “suffer tomorrow,” the band’s strolling mellow groove, splashing a dramatic accent at “destined to die,” supports Bilal’s capturing of Gaye’s force with chilling effectiveness. A masterful narrator, Bilal builds the tension of the first chorus to the dynamically exclaimed point of the song, “save the children!” After the word “children” is held for seven beats, his falsetto cry of “save the babies!” follows. Then, at 3:23, the mood shifts for an engaging second modal chorus at medium tempo. Bilal sings with increased emotion meshed with Fischer’s and tenor saxophonist Caleb Wheeler Curtis’s improvisational support.

“Sunday in New York,” as expected, brings together Evans’s Philadelphia-based community of talent to perform trombonist Gibson’s engaging arrangement, which ripples with anticipations of the beat. Gibson changes the colors and dynamics of the band throughout, not to mention providing the opportunity for alto saxophonist Todd Bashore to develop and extended solo. However, the track’s highlight is Joanna Pascale’s capture of the carefree cheerfulness of the song written by Peter Nero, who for 34 years was the musical director of Peter Nero and the Philly POPS. Pascale draws attention to the lyrics at the very start of the piece by singing the first word, “New,” not on the first beat but on the third as “New” swells into the second measure of “York on Sunday.” Like an instrumentalist, she crafts each note rhythmically and sonically, such as when she sings the word “two” over four beats (as “two” becomes “oooo”) before “hearts stop beating,” the remainder of the phrase, catches up at a faster pace.

Bashore’s masterful rumba arrangement of Bread’s 1971 hit, “If,” seems to have been written to feature composer and vocalist Paul Jost’s talent. During one chorus, Jost leads with an accompaniment solely by Evans. During another, Jost and the big band rise in volume and force. The throbbing vamp of “Dislocation Blues,” introduced by Evans and by Anthony Tidd’s electric bass, sets up the foundation for Jost’s initial narrative to evolve into a blues shout and then a fadeout.

The high standard of Walk a Mile in My Shoe’s vocal excellence of continues when Grammy-winner Lisa Fischer deliver not just one, but two, tours de force. Her exciting interpretation of “Blues in the Night” provides an example of her total immersion in a song and the thrill of her broad range. Josh Lawrence arranged Stevie Wonder’s “Overjoyed” in a mellower tone than “Blues in the Night” to highlight the stylistic contributions of Fischer and fellow trumpeter Payton.

Wryly, Evans includes Gibson’s arrangement of “Smoke Gets in Your Eyes,” comprising but 3-1/4 minutes, as a grateful reference to the club itself. The track features the blends of the horns with a chorale-like palette minus a rhythm section, its calmness and hues realizing the possibilities of the song’s harmonic beauty.

And, backed by the Captain Black Big Band, Evans performs “Hymn” without rhythm, as if, similar to the approach to “Smoke Gets in Your Eyes,” the blossoming of the band’s accompanying chords occurs not metronomically, but naturally. “Hymn” having been written by a founding member of the Captain Black Big Band, John Raymond has moved on to accept the position of Associate Professor of Jazz Studies at Indiana University. Nonetheless, the soulful solemnity of “Hymn” indicates that his influence remains.

As Orrin Evans builds his thoughtful, soulful, joyful, and innovative discography, he continues to go in unanticipated directions. Evans consistently retains in all his recordings the involvement of his community in the creation of jazz and the importance of the humanity that enlivens the art form.

Artist’s Web Site: https://orrinevansmusic.com

Label’s Web Site: https://orrinevansimani.bandcamp.com/album/walk-a-mile-in-my-shoe