John Pizzarelli has had his share of musical heroes, and he has recorded albums as tributes to them. There’s Nat Cole (Dear Mr. Cole). Paul McCartney (Midnight McCartney). George Shearing (The Rare Delight of You). Duke Ellington (Rockin’ in Rhythm). Johnny Mercer (John Pizzarelli Salutes Johnny Mercer). Rosemary Clooney (Live at Birdland). Dave Frishberg (Knowing You). Richard Rodgers (With a Song in My Heart). Neil Young (Double Exposure).

And then there’s his musical hero supreme, Bucky Pizzarelli (Generations).

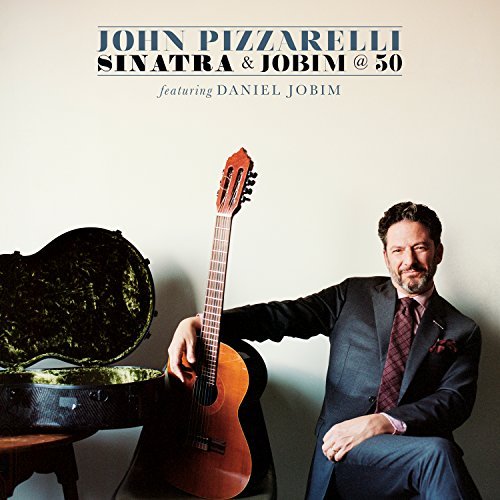

But John Pizzarelli has always been in awe of another legend, Frank Sinatra (Dear Mr. Sinatra). A major influence on singers who followed him, including of course Pizzarelli, Sinatra finally got the opportunity to explore other musical pathways later in his career after he founded his own label. Pizzarelli frequently reminisces about his only “conversation” with Sinatra, when Ol’ Blue Eyes told him, “Eat something. You look bad.” So much for a kind word to a fan. Nonetheless, Pizzarelli’s admiration didn’t diminish, particularly when he got to experience an audience’s reaction to Sinatra’s presence, which he describes as “electric.” Pizzarelli felt that electricity too.

Being influenced by bossa nova as well, Pizzarelli had recorded an album appropriately named Bossa Nova as a tribute to João Gilberto. Eventually, Pizzarelli @ 57 realized that 2017 would mark the fiftieth anniversary of the recording of Francis Albert Sinatra & Antônio Carlos Jobim—an album that marked the confluence of cultures of separate continents and the unity of spirit inspired by music. It turned out that Jobim’s grandson, Daniel Jobim @ 44 (who participated in the recording of Bossa Nova) was just as enthusiastic about recognizing the significance of the 1967 album and bringing it to the attention of another generation.

Now they have done that.

Pizzarelli and Jobim set out to choose some of the songs from the original Sinatra-Jobim album and to add some of their own—imagining what would have happened if the icons’ “relationship had continued.” That imagination continues now through another generation, though these singers have voices of their own, instead of imitating the Sinatra baritone or the inviting relaxation of Jobim’s approach. Their voices: Pizzarelli’s familiar now from the numerous albums he has recorded, his wit and swing and immersion into the songs ever apparent; Jobim, not as familiar, though he has of course a following in his native country in capturing the Brazilian story-telling-through-song.

As on Francis Albert Sinatra & Antônio Carlos Jobim, Pizzarelli and Jobim mix American standards with Brazilian compositions. For the most part, they’re the same on both albums, though the sequences are rearranged to some extent. For instance the Sinatra-Jobim album begins with “The Girl from Ipanema,” while the Pizzarelli-Jobim album starts with “Baubles, Bangles and Beads,” the latter song being the first track on the latter album. “The Girl from Ipanema” didn’t quite make it to the new album. But then, “The Girl from Ipanema” was enjoying a high degree of popularity in 1967. Pizzarelli does recall the song, though, by inserting a line from it into “Antonio’s Song,” the Michael Franks tribute to Jobim. Nonetheless, several of the Jobim-written Brazilian songs do appear on Sinatra & Jobim @ 50.

Instead of being cowed by reverence to the first album’s style, Pizzarelli and Jobim thankfully chose not to create a replication of it. Instead, (1) they decided to record with a back-up trio, and with the occasional tenor sax solo by Harry Allen and background vocals, instead of with a studio orchestra (led by Claus Ogerman in 1967); (2) they increased the length of the recording from the original’s 28 minutes to accommodate the present-day expectation of about twice that much music on an album (theirs being 51 minutes); and (3) they added their own compositions as a means of expansion, as tributes, and for personal expression.

Speaking of the back-up trio, however, Pizzarelli’s consists of pianist Helio Alves and drummer Duduka Da Fonseca, who provide the Brazilian feel crucial to the spirit of the music. Teaming up with bassist Mike Karn, plus Pizzarelli’s guitar work, the rhythm section sets up the ease and sway characteristic of bossa nova, which is particularly noticeable on the medley of “I Concentrate on You” and “Wave.” Pizzarelli’s includes his own stylistic trademarks on “Agua De Beber,” as he performs the unison guitar and voice improvisation several choruses after he and Alves combine for the unison presentations of melody.

The duets with Daniel Jobim jelled from afar after Jobim contributed his parts from Sito Poco Fundo in Rio de Janeiro. The most difficult audio engineering feat was that for Jobim’s “Two Kites,” which was an absolute imperative because Bucky Pizzarelli, John’s father, recorded it with Antônio Carlos Jobim on the 1980 album, Terra Brasilis, along with Bob Cranshaw and Grady Tate (and Ogerman’s orchestra, of course).

Pizzarelli and his wife, Broadway actress Jessica Molaskey, wrote the album’s two new songs, “She’s So Sensitive,” a love song substituting for “How Insensitive” from the 1967 album, and “Canto Casual,” lightly re-creating the Rio carnival atmosphere with percussion, a final Alves solo, guitar licks and its repeated sung phrases.

So the lesson of Sinatra & Jobim @ 50 is: Be careful when giving advice, however caustic it may be. It may inspire a tribute a half century later.

Artist’s site: www.johnpizzarelli.com

Label’s site: www.concordmusicgroup.com