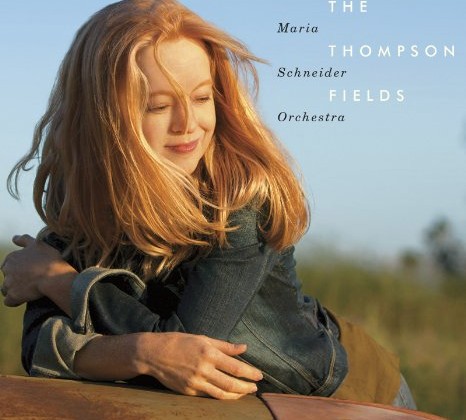

Having gloriously reminisced about her childhood hometown throughout her orchestral masterpiece, TheThompson Fields, it’s time for some contrast. In fact, Maria Schneider’s Data Lords album consistently contrasts the melodious essence of the natural environment—full of birds’ chirping, thunder’s rumbling, leaves’ swooshes and rustling, joyful songs and mournful elegies, flowing water’s susurration, hail’s popping, or dry thistle’s quiet smacking—with the invented surroundings of massive and exponentially expanding amounts of digital influences upon human life.

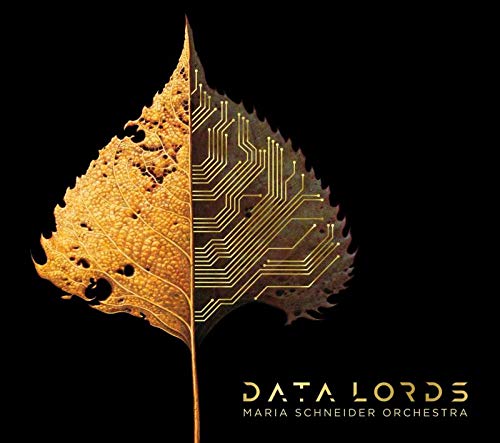

Schneider’s representations of the contrasts couldn’t be more obvious, and more effective. The consistency of her masterful presentation of her theme excels, from the package’s symbol of an exquisitely rendered split image of an apparently autumnal leaf mirrored by a shape of electronic circuitry, to the fact that the musical statements contained within the package are separately sleeved, as if incompatible. Schneider would be a person who understands this paradox behind contemporary tensions as the musical sounds of the fields and of the gravel paths of her childhood collide with the electronically produced and/or accessed music that describes experiences of much of today’s childhood—and adulthood. Rather than repeating The Thompson Fields’ appreciation of nature and restating the profundity of life’s immemorial simplicities, Data Lords comprises a musical essay about a universal twenty-first-century tension with all of the talent at Schneider’s and the Orchestra’s command.

Instinctively predicting where the sacrifice of art to data and commerce would lead, Schneider was the first jazz artist to crowd-fund through ArtistShare her album Concert in the Garden, as she avoided selling it through major labels, which still released the majority of the highly promoted jazz recordings in 2004. Her opposition to the appropriation of intellectual property has continued to simmer. Schneider realized that music reduced to data would be devalued to dollars to pennies to nothing. Schneider has testified before Congress about intellectual property rights and protection from the digital “data lords.”

Yet, Schneider hasn’t forgotten the peaceful eternal beauty of Midwestern nature, even as she combines it with the musical energy of New York-based jazz gained as Gil Evans’ assistant and Bob Brookmeyer’s apprentice. One would think that The Thompson Fields, an immensely moving and significant recording, would be the capstone of Schneider’s discography. But further consideration of her concerns would have suggested that she had other worthy themes on her mind besides natural harmony, or harmonious nature.

Who knew but Schneider that her defense of the value of art would eventually be the basis for another work of art?

Too complex to be contained by a small group, Schneider’s ideas and compositional movements and kaleidoscopic colors have been expressed consistently throughout 28 years by her Maria Schneider Orchestra.

Which brings us to the music. The gorgeous music. Gorgeous even when she suggests darkly the deleterious effects of, not merely an industry, but a universe of ever-present “information technology.” Gorgeous especially as she celebrates, in the end, the overwhelming thrill of a rising sun.

The fact that Schneider has kept many of the same musicians for most of her Orchestra’s existence has made its now-familiar musicians’ voices recognizable, the consistency similar in concept to the continuity of the individual styles of the Duke Ellington Orchestra’s members, for example. There’s pianist Frank Kimbrough’s pensiveness, his calmness evident even in the midst of rising big band puissance. There’s the sweetness of Steve Wilson’s fluttering and darting saxophone, no doubt re-creating the bird sounds that Schneider hears. There’s the melodiousness of Marshall Gilkes’ trombone as he sings through his vignette-like solos. There’s the obliqueness of Rich Perry’s fun-house mirroring of themes, turning them into something besides straight-ahead improvisations. And there’s the twittering and sighing of Gary Versace’s accordion, surely the most unconventional instrument in the Orchestra, but one that realizes Schneider’s visions. However, the most irresistible voice of all is that of Schneider’s entire Orchestra, one whose magnificent hues include the entire spectrum of a big band’s register, from George Flynn’s bass trombone and Scott Robinson’s contrabass clarinet to Dave Pietro’s piccolo.

Schneider booklet (yes, Schneider’s albums include full booklets and not merely liner notes) starts the description of her project with The Digital World, although, of course, one can listen to either album first. Her description appears to lead from the darkness and the mind control of the “data lords” to a resolution by peace of mind provided by nature.

Schneider isn’t shy about naming names. She ridicules Google’s slogan of “Don’t Be Evil” as “they set the bar so low.” Schneider can’t help herself. In the midst of “Don’t Be Evil’s,” her jazz composition’s, ridicule, she creates beauty. Flynn’s bass trombone and Ben Monder’s guitar set up a comical, otherworldly pattern upon which the band builds, typically with room for elaborating solos from Monder, Kimbrough, trombonist Ryan Keberle and bassist Jay Anderson.

Completely frank in her disdain, Schneider writes that “we musicians have had our eyes on [big data companies] for years. We were among the first to see our life works exploited and traded on the internet for data. Now, nearly everyone’s life is similarly exploited.” Her “Data Lords” composition, an expression of alarm apparently influenced by Gil Evans’ modal arrangements for Miles Davis’ Sketches of Spain, is distinguished by Mike Rodriguez’s electronically modified trumpet solo and Pietro’s extended passionate alto sax solo. The band’s back-up tension builds the performance to a chaotic free-jazz breaking point.

But all is not data lord fear and disgust. Schneider’s “Sputnik” recalls the launch of Russia’s satellite that launched the U.S. space race that resulted in a manned satellite and the landing on the moon. More aspirational and calm than other tracks, “Sputnik,” cinematic in its awe, features Scott Robinson, a baritone saxophonist with yet another identifiable sound, as he improvises from deep within the instrument to its on-pitch altissimo singing, sounding at times more like an alto sax, as the broad orchestra colors shift behind him. And taking sonic inspiration from an unlikely, but in the end obvious, source, the Morse Code, “CQ, CQ Is Anybody There?” is a tribute, and now eventual understanding, of her father’s commitment to his ham radio hobby. Schneider points out that the ham radio was in some ways similar to the Internet with its electronic ability to connect to other human beings. The difference was accountability; no one’s identity on ham radio’s could be hidden. Ingeniously, Schneider bases the rhythms of “CQ, CQ Is Anybody There?” on those of the Morse Code. This time, Greg Gisbert electronically alters his trumpeted solo to comment on Morse Code messaging while the band’s sound grows and punches in repeated code pitches.

In the end, Schneider misses, if not mourns, “A World Lost,” of childhood play and peace of mind. She remembers the simplest discoveries of nature, and her concern involves the frenetic pace of today’s childhood not allowing for imagination. The haunting minor-key theme expressed initially by lower-register instruments amplifies Monder’s eerie solo and Rich Perry’s contrasting calmness on tenor sax.

The contrasting differences of Schneider’s Our Natural World album within the same package as The Digital World bring the listener back to the majestic tracks of The Thompson Fields. Instead of loss and fear, Our Natural World celebrates discovery, peacefulness, joy, wonder, fun, beauty and nature. While Monder’s guitar and Rodriguez and Gisbert’s electronically modified trumpeting were the primary instruments to bring into being Schneider’s feelings about the “data lords,” Versace’s accordion, Gilkes’ trombone and Steven Wilson’s soprano sax are featured to create the sounds of nature that Schneider wants. Instead of dark soundscapes of The Digital World, Our Natural World usually involves melodies, while the solos of accomplished musicians tell stories.

It seems that the word “majestic” just can’t be avoided when writing about Schneider’s recordings. Eventually, her albums include unabashed majestic feelings, usually about nature. “Majestic” just happens to be the correct adjective to describe her music. Recognizing the possibilities afforded by Gilkes’ sound, Schneider wrote “Look Up” to feature his breezy style and smooth tone as a way to indicate, yes, majestically, that the human spirit can be recharged just by looking up at the sky.

Our Natural World includes compositions arising from Schneider’s sense of fun as well. With the broad spectrum of the orchestra’s sound moving mysteriously at first, “Sanzenin” evolves into Versace’s dynamically broad accordion solo, an minimalist, respectful evocation of joy inspired by the gardens of a Japanese Buddhist temple. Versace’s artistry takes flight, though, on “Bluebird” as he improvises on accordion without restraint in Versace’s most exciting performance on any of Schneider’s albums. Versace lets anyone know how impressive the accordion can be and also how a master of the instrument like himself can express sounds of nature and a sense of frolic as easily as can traditional big band instruments.

Schneider teases with “Stone Song,” which involves the Japanese concept of the “voice in the stone.” Setting a Japanese stone beside her as she composed it, “Stone Song” features Wilson on soprano sax performing his comical, jabbing stop-and-start melody, accented off meter by the band as Kimbrough’s insistent treble chords, Anderson’s pulse and drummer Johnathan Blake’s back-up rhythmless textures alternate with suspenseful silence.

Majestic too is “Braided Together,” based upon a poem by Schneider’s favorite poet, Ted Kooser. Quietly moving through lines accented by Anderson’s bass and Kimbrough’s piano, Pietro’s alto sax presents the theme while alluding to Schneider’s melody, the band’s lush background chords entirely majestic. Majestic is “The Sun Waited for Me,” based on another Kooser poem, its hues magnificently bright . The Maria Schneider Orchestra’s sound is unmistakable on this track as it goes from beautiful melody to thrilling conclusion. “The Sun Waited for Me” is equivalent to The Thompson Fields’ “Waiting by Flashlight” when it revels in natural wonders with a memorable melody brought forth again by Gilkes’ trombone.

In the Data Lords package, Kooser represents a down-to-earth counterweight to the massive influence of information technology, as Kooser creates thoughts with words like these: “How important it must be / to someone / that I am alive, and walking, / and that I have written / these poems.”

This isn’t the first time that people have feared materialistic intrusion that disrupts nature. In 1802, William Wordsworth wrote about the abandonment of nature for “getting and spending.” “The world is too much with us… / Little we see in Nature that is ours; / We have given our hearts away, a sordid boon!”

But we’re still here. 218 years later.

So is nature. With its microscopically detailed and incomprehensibly vast panoramic beauty.

And so is the tension between materialistic attractions and natural wonders.

It’s comforting for Schneider…and us…to know that her pursuit of beauty, and similar pursuits by other artists, won’t merely endure.

They will prevail.

Artist: http://www.mariaschneider.com

Label: www.artistshare.com