Even though they constitute the bulwark of most jazz groups, grounding them in rhythm and atmosphere, bass players appear to be the most modest of musicians, rarely attaining the recognition of guitar, horn and keyboard players, not to mention drummers, except for outsized personalities like Jaco Pastorius or Charles Mingus. And yet, bass players, like Ron Carter or Ugonna Okegwo, while gracefully providing the pulse for jazz groups (and indeed, walking bass lines can be musical synecdoche for jazz itself) often without notice have earned advanced degrees and have explored numerous musical genres besides the jazz trio. How often has the bassist’s respectful professionalism caused someone to wonder about stories they have to tell?

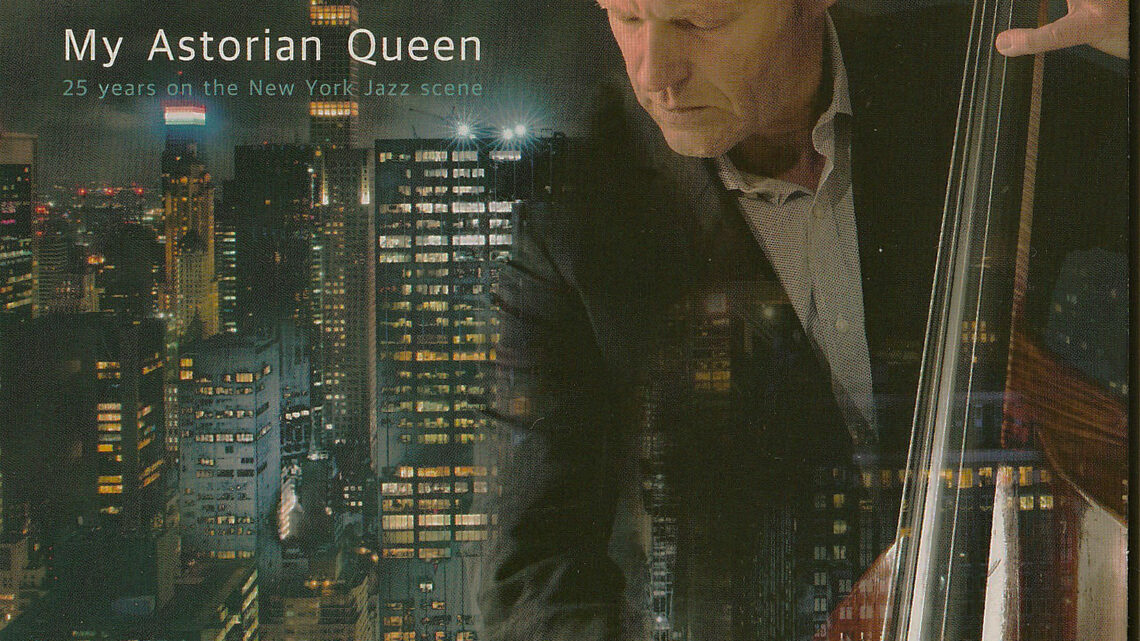

Martin Wind, a New York-based bassist, has quite a few stories to tell.

Some of those stories are represented on the latest of his 20+ albums as a leader or co-leader—and on over 70 albums as an accompanist—as well as being the bassist for the Kennedy Center Honors and performing in Broadway orchestras and on tracks for movies like Gemini Man.

Not only is My Astorian Queen dedicated to his wife of 25 years, Maria. Also, the album is a recollection of the ways that New York helped to shape his life and his music after he moved there in 1996.

A theme that usually arises from New York City-based musicians isn’t one that jazz listeners in other parts of the United States would expect.

That theme? It’s the kind spirit of the New York jazz community.

Rather than the competitive struggle suggested by the song, “New York, New York,” wherein one aspires to be “king of the hill” and “top of the heap,” the truth is that jazz musicians usually welcome and assist newcomers.

Bassist Wind was yet another jazz musician who discovered the metropolis’s welcome mat when he moved to New York 25 years ago from his hometown of Flensburg, Germany, located in the state of Schleswig-Holstein only a few miles from the Danish border.

After graduating from the Music Conservatory in Cologne, a scholarship from the German Academic Exchange Service helped him finance graduate studies at New York University in 1996.

Wind visited New York tentatively in 1995 at the encouragement of pianist Bill Mays, who heard him perform with a Dutch group at the North Seas Jazz Festival.

Bill Mays. Who also mentored Bill Charlap at the very start of his career. And no doubt many other jazz musicians. Tell us your story sometime, Mr. Mays. About your kind contributions to jazz communities around the world, among other things.

During a dinner in New York with Mays and his wife on his second day in the U.S. in 1995, Wind met Maria. In addition, Wind won the third-place award the same year in the Thelonious Monk Bass Competition, although he doesn’t mention that honor much, as is the modest wont of bassists. Wind was impressed with abundance of jazz talent in New York—and later “living a dream” of playing with many of the jazz masters—the plentitude of which inspired him to move there. He reconnected with Maria that year later and then married his Astorian queen, in the community of Astoria in Queens.

Wind starts his musical recollections of his times in New York with Thad Jones’s “Mean What You Say,” a tribute to Wind’s tenure in the Vanguard Jazz Orchestra. Mays starts the performance with a three-chorus graceful-as-always piano solo, delivered with the ease of a seasoned professional who has performed with the who’s who’s of jazz like Sarah Vaughan, Gerry Mulligan, Jimmy Cobb, Toots Thielemans, and Phil Woods.

Well, all of the members of Wind’s quartet are seasoned professionals, including two more long-time friends/collaborators.

One is the exceedingly versatile Scott Robinson, whose mastery of numerous horns acquits him well in any jazz situation. Famously, Robinson’s alto clarinet provided exactly the sonority that Maria Schneider sought for her recording of “Walking by Flashlight” on her album, The Thompson Fields. But that’s but just one album out of more than 300 to which Robinson has participated or led. Not just a collector, but also a performer, of rare instruments, Robinson owns a theramin, a flute, a bass saxophone, a C-melody saxophone, a sarrusophone, a contrabass clarinet, a ophicleide…and more. So dedicated is Robinson to his music that he wears a hat made out of 200 reeds from his saxophones.

The other is Matt Wilson, who has developed his own persona on sometimes quirky albums (with tracks like “Old Porch Swing,” which is exactly what his solo drum work imitates). Nonetheless, all of Wilson’s albums suggest heartfelt recognition of his hometown in rural Knoxville, Illinois by recalling high-school football games and auctioneers; and the suggested love of family, including his Big Happy Family of fellow musicians.

Springing along with insouciance and happiness, Wind’s bass lines lope as “Mean What You Say” features Robinson on trumpet, showing an infrequent mastery of both brass and reed instruments. Keeping the performance light and brisk, the quartet recalls the outstanding acoustics of the Village Vanguard, something that Wind never forgot from decades ago, as well as the unforgettable collaboration of Jones and Mel Lewis.

The first of Wind’s three compositions on the album, “Solitude,” proves once again, as occurred on some of Schneider’s albums, that Robinson can adapt to the mood and colors of compositions by changing to the instrument needed for the required effect. Wind’s “Solitude,” which recalls the placid, multi-hued beauty of the Flensburg Fjord, attains expression with Robinson’s switch to clarinet.

Characterized by the suggestion of a tango rhythm and the pensiveness of a medium-tempo minor-key melody of several apparent key changes, Wind, Robinson and Mays perform that melody without undue improvisation, except when Mays’s accompanying chiming of spare treble chords of fourths and fifths evolve logically into an elegant affecting solo built upon them and rising tremolos. Wind’s second composition, “Out in P.A.,” recalls Wind and his wife’s trips to Mays’s home near Shohola, Pennsylvania (or “P.A.”). Wind refers to Mays’s home as a “magical place,” and it seems to be that since Mays recorded an album about his home, Going Home, on which Wind and Wilson participated too. Recorded first on Mays’s 2000 album of the same name, “Out in P.A.,” after a peaceful opening that Wind performs as an arco solo over Mays’s coruscating colors, at first seems to be like “Solitude,” its minor key, similar tempo and adherence to melody similar. But not as succinct as Wind’s “Solitude,” “Out in P.A.” gathers force and intensity throughout the track as Robinson’s interpretation on tenor sax rises to an altissimo exclamation point and as Wilson adds more agitation and textures.

Mays’s contribution to My Astorian Queen is his “Peace Waltz,” from One to One 2 with Ray Drummond, which Wind says is his favorite Mays composition. A trend emerging from Wind’s compositions and his favorite pieces, including Bill Evans’s “Turn Out the Stars,” appears to be his preference for the Romantic Era’s integration with jazz. The amalgam includes emotional musical stories with wide ranges of pitch and dynamics, unconventional harmonies, as well as dramatic sweep and vibrancy. Mays’s beautiful touch on the piano and his ringing chords certainly assist in the expressiveness that Wind likes. Again, Mays performs a varied soulful solo consisting of a roaring crescendo, drifting falling-leaves-like chords, a march-like call and response, a nimble single-note frolic—all of which ends, in a minor key again, like the final notes of “A Taste of Honey,” but with stunning virtuosity. The ending itself moves through several moods, first with Wind’s moving, melodic performance accompanied only by Mays. When Mays takes over with fortissimo cinematic flourishes, emphatic accented chords, and glittering treble-clef ornamentation, the dynamics weaken into a repetition with a difference of just five sustained rubato chords fading warmly to a piano volume colored by Wind’s softly buzzing tremolo.

One of Wind’s Brazilian students at New York University brought to his attention “É Preciso Perduar,” popularized by João Gilberto and Stan Getz and recorded afterward by other jazz artists like Flora Purim, Grover Washington, Jr., and Gretchen Parlato. In a breezily swaying interpretation, Wind converts the primary melody to an improvised melody of his own in between Robinson’s warm delivery of the song. Appropriately, the track includes an extended finely textured drum solo framed by the tune’s signature vamp. Interestingly, Robinson switches to bass saxophone to join with Wind and Mays when playing the accompanying vamp over Wilson’s light danceable rhythms.

While “Solitude” expresses Wind’s fondness for his boyhood home in Flensburg, three of the other tracks on My Astorian Queen depict the excitement of the New York music scene: “Broadway,” “There’s a Boat That’s Leaving Soon for New York,” and “New York, New York.” “Broadway” recalls Wind’s involvement in the orchestras for Phantom of the Opera and his favorite Broadway play, Kiss Me Kate, for which Don Sebesky provided the arrangements. The quartet’s joy in playing the song comes through loud and clear, especially as a result of Robinson’s playing the entire song on bass saxophone over the rhythm section’s exuberant re-harmonized accents. Then, never ceasing to impress jazz listeners with his instrumental resourcefulness, Robinson changes to trumpet, with a blissful open tone and occasional vibrato, on “There’s a Boat That’s Leaving Soon for New York,” which suggests the excitement of searching for a new home there. Wind alternates the vamp, melody, rhythm and double-stop harmony on “New York, New York” on his solo performance, backed solely by Wilson’s loose and light drum work consisting of clapping cymbals, backbeat accents, beats in unison with the melody, and a final drum roll as Wind ends the final track of his album.

Backing up to the title track, though, “My Astorian Queen” celebrates the unifying component of his experiences in New York, his wife, Maria, with whom he has shared his last 25 years, along with his two sons. The wistful waltz receives graceful tenderness from Wind’s initial solo through Robinson’s elegant stylings with a romantic legato tone on tenor sax. In addition, My Astorian Queen represents Wind’s gratitude for his good fortune, his acceptance in a new country, and the New York musical community where he has prospered.

Quite a story.

Artist’s web site: https://martinwind.com/

Label’s web site: www.laika-records.com