Much remains to be written about the resultant health care, cultural, economic, political, and social challenges wreaked by the COVID pandemic. And much remains to be written about the experiences during the first viral pandemic to occur in a hundred years.

The documentation to be written about the pandemic hasn’t been, isn’t, and won’t be written just in words. It may be written in music too.

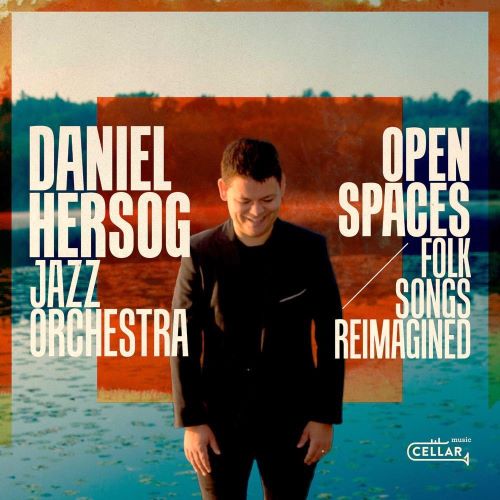

Trumpeter, composer, arranger, and orchestra leader Daniel Hersog has released his second album, once again inspired by his community concerns.

Open Spaces: Folk Songs Reimagined arose from Hersog’s meditations during the imposed, fearsome solitude of the COVID epidemic—the first “social distancing” and mass quarantining that existing citizens of the world had ever experienced.

Hersog’s thoughts took him back to his childhood, a time when it seemed to him that people came together instead of being separated. While he composed and arranged music for his second album, Hersog intended that the music of Open Spaces: Folk Songs Reimagined provide comfort in times of great stress as it evokes some legends, customs, natural environments, and phrases of his homeland: Canada.

Appropriately, Hersog’s magnificent new album was recorded in Vancouver, where he lives, and it has been released on the Vancouver-based label, Cellar Music.

The majority of musicians in the 17-member Daniel Hersog Jazz Orchestra consists of Vancouver residents like Brad Turner and Tom Keenlyside, with whom Hersog has performed often in local venues. However, flown from the United States were many of other musicians, some of whom—like Frank Carlberg, Noah Preminger, and Kim Cass—he met while attending the New England Conservatory, from which Hersog graduated in 2016. Other adventurous New York musicians in the orchestra include Dan Weiss, Scott Robinson, and Ben Kono.

Hersog modeled his first album, Night Devoid of Stars, after the warm orchestrations of Gil Evans, whose richly voiced blend of instruments provided an uplifting environment of gliding movement behind improvising soloists. The rise of an outstanding arranger like Hersog indicates the continuing influence of Evans’s innovative musical ideas as he changed the sounds of a jazz orchestra. Open Space: Folk Songs Reimagined continues Hersog’s methods inspired by Evans that extend horizontal phrasing over the bar lines, while allowing for moments of shattering intensity and dynamic expansion, sudden or eventual.

Yet, Hersog’s style, influenced though it was by his predecessors, including Bob Brookmeyer’s, has quickly developed into his own. Hersog’s music involves his astute social conscience and his concerned outreach to communities, instead of introspection. It takes the form of intentionally uncomplicated recalled melodies (blossoming always into pulchritudinous complexities), onomatopoetic moments, national pride, and cultural narratives. By laying the groundwork for exceptional improvisers to latch onto and interpret his ideas, Hersog combines the largeness of a unified orchestral sound with the passionate contributions of individual soloists.

Open Space: Folk Songs Reimagined begins with one of Ontario-born Gordon Lightfoot’s most dramatic songs. Working with Lightfoot’s sung narrative poem, “The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald,” Hersog, as the title of his album states, reimagines the event in a five-four meter. Three minor-key sonic scenes develop: (1) the sea shanty as the crew sails across Lake Superior, the ship’s progress indicated by bass-clef accents undulating under the melody and Preminger’s exploratory solo; at 2:06, the thunderous storm in free rhythm depicted by Carlberg’s shattered clusters and Weiss’s crashing of cymbals and drummed depiction of chaos; and at 2:50, Hersog’s extended, more harmonious voicings and bagpipe-like droned embellishments. The gradual crescendo suggests social normalcy washing over the wreck as daily work resumes, much as the ocean’s calming surface can hide tragedies beneath it.

Hersog considers Bob Dylan’s “Blowin’ in the Wind” as an inspiration for his composition, “How Many Roads,” which quotes a phrase from the songwriter, an American born near the Canadian border in Duluth, Minnesota. Hersog’s reimagining of, rather than the repetition of, the famous melody, emphasizes instead images of the wind’s mild wafting. The woodwinds paint the arrangement’s multi-hued portrait, and Carlberg evolves an upper-register piano pattern into an expanded stirring solo. With quick embellishments like 16th-note up-swept phrases over a single beat and suggestions of sunrise, “How Many Roads” establishes its own musical identity without obvious derivation. “How Many Roads” depicts a breeze’s ethereal peacefulness and sweep, rather than the unresolved questions and quest of “Blowin’ in the Wind,” whose words no doubt reflect Hersog’s social conscience.

After the scenic orchestrations of the first two tracks, Hersog defies expectations by exploring in four a Canadian rock song, “Ahead by a Century.” Hersog converts the song into a joyous orchestral version, with prodding pulse and brass-led call-and-response, that provides improvisational opportunities for soprano saxophonist Kono and trumpeter Turner. Again, Carlberg single-handedly changes the arrangement’s perspective at the track’s ending by briefly freeing the piece’s rhythm and tonality with tremolos and unbounded scampering.

Similarly, Hersog’s “I Hear,” based upon the French-Canadian song “J-entends le moulin,” delivers a fiery, ominous, vertiginous atmosphere in several movements that allows for individual interpretations by Preminger, Kono and Turner. The initial fortissimo lower-register beats of one, then two, and then three, contrasts with the reed instruments’ treble-clef fluttering, the piano’s glass-like tinkling, and unmoored brass lines. The impressionistic introduction moves at :42 into Preminger’s tenor sax solo, backed by Cass’s energetic bass lines and the textures of Weiss’s drumming (reminding the listener of the rhythm section’s important contributions to the orchestra’s distinctive sound).

While Hersog acknowledges Gil Evans’s influence on his style, it appears that Henry Mancini provided Hersog with ideas too. At 2:24 and 3:14, a powerful vamp reminiscent of Mancini’s Peter Gunn theme emerges. At 2:33, a change of mood refers to the circus-like anything-goes wackiness of Raymond Scott, complete with boom-chik four-four accompaniment and equine whinnying. But not for long. A medium-tempo hard swing accented by trumpets’ pow’s develops. Hersog’s arrangement moves quickly from mood to mood, providing additional groundwork for Kono’s, Turner’s, and Weiss’s solos.

But back to folk songs’ ability to provide solace to Hersog during the pandemic.

“Shenandoah,” a folk song from the early nineteenth century sung, according to legend, by French fur trappers, features another subtle but emotionally charged solo for the ages by Scott Robinson, this time on baritone saxophone (his other being his alto clarinet interpretation of Maria Schneider’s “Walking by Flashlight” on The Thompson Fields). Opening the song as if as a sunrise, the introductory tonal palette of Kono’s oboe, Keenlyside’s flute, and Ben Henriques’s clarinet blend into a sustained tonic chord until :47 (which is basically a seamless repetition of the first measure). Then bar two of “Shenandoah,” re-harmonized, enters at 1:09 as the lead-in to the warmth of Robinson’s solo, accompanied throughout by Carlberg’s rippling treble notes. The arrangement concludes with the orchestra’s unison rubato performance of the song.

Popular in both Canada and the United States as a song about the river dividing Minnesota and North Dakota and flowing northward through Manitoba, “Red River Valley” was another folk song that brought Hersog some peace during the pandemic. After Hersog’s orchestrally flowing first choruses, leisurely presented over re-harmonized phrases in largo tempo, guitarist Kurt Rosenwinkel delivers a relatively straightforward single-string delivery of the melody in country-western style after a key change. He then improvises with greater agitation over thicker background orchestral voicings. Surprisingly, but appropriately, the song’s lyrics are sung over Rosenwinkel’s comping, recalling Hersog’s affection for the communal spirit of campfire songs.

Hersog wrote his own folk song for the album as well, called, fittingly enough, “Canadian Folk Song.” Rosenwinkel begins the track unaccompanied with a more elegant introduction than that of “Red River Valley’s.” The performance of Hersog’s song in three-four receives Rosenwinkel’s initially lilting delivery, respectfully played with melodic directness. Preminger and Carlberg take the song in their own directions, Preminger with swaying throaty bluesiness and Carlberg in two-chord dissonant crystallinity reminiscent of “Peace Piece.” The relatively dramatic but stately ending anchored by a pedal point rises beautifully to the flute’s and bass clarinet’s final tones.

Once again, Daniel Hersog has created another significant accomplishment arising from his firm social conscience and original personalized arrangements that reinforce his importance in shaping the continuing development of jazz orchestras.

Artist’s Web Site: danielhersog.com

Label’s Web Site: cellarlive.com