Always unpredictable and free thinking, who else but Mostly Other People Do the Killing would produce with precisely matched tempos a note-by-note re-recording of one of jazz tradition’s most hallowed albums of all time, Miles Davis’s Kind of Blue? Who else would challenge the accepted groupthink of jazz wisdom that dismisses the popularity of smooth jazz of the seventies and eighties by recording Slippery Rock, the group’s tribute to that disrespected style? By provoking occasional, intentionally in-your-face controversy with a scampish twinkle of the eye, as if pranking jazz purists, the mutable members of MOPDtK record jazz whose sometimes controversial attitudes may divert attention from its members’ high level of musicianship.

MOPDtK’s new album, Disasters Vol. I, with an unsurprising touch of irony, reinforces the truth of the rules-breaking group’s name, intentionally or not. The titles of the compositions on the album refer mostly to the sites of Industrial Age disasters from man-made devices. The disasters are remembered, even decades or a century later, in the cities where they occurred.

The cities whose residents suffered so much.

It’s well-known by now that Elliott has titled some of his albums (like Red Hot) and compositions (like “Rough and Ready”) after the names of cities in Pennsylvania because they match his penchant for oddity. Of course, cities in other states, such as Jot ‘Em Down, Texas; Good Grief, Idaho; or Dummer, New Hampshire, share intriguing names too. But the large number of unusual names of towns in Pennsylvania could provide Scranton-born Elliott with risible titles for numerous albums in the future.

The names of the towns in MOPDtK’s most recent album don’t cause the listener to smile as much as to reflect. Elliott’s spirited interpretations of some of Pennsylvania’s disasters dramatize the sacrifices of industrial progress, whose motto often was “Quabity First.” Strickened citizens unrelated to the making of failed manufactured products, poor engineering designs, unfortunate transportation decisions, and toxic industrial byproducts paid a steep price. So much so that the man-made failures have become classified as disasters embedded in Pennsylvania’s history.

Of course, other states have experienced devastating disasters from natural, terrorist, industrial, military, or negligent causes. Just ask the residents of Louisiana, New York, Kentucky, Hawaii, or California.

But Elliott writes music about what he knows, and he knows Pennsylvania. Elliott gets his Scrant on for furthering awareness of, and then perhaps Reading about, the state’s towns, if only, perhaps, because the ridiculousness of their names inspires him.

Question: How do the citizens feel about compositions being named for their towns because of famous disasters or due to the ludicrousness of their towns’ names?

It turns out that Elliott’s purpose, loyal to Pennsylvania as it may seem, is larger than focusing on particular communities. His compositions suggest the still-relevant universal issues that surrounded the disasters.

So how would a composer write music about disasters resulting in loss of life without depressing listeners, thereby discouraging interest? One would expect solemnity, dirge-like melodies, spiritual inspiration toward recovery, and gravity. (Sure enough, there’s a Pennsylvania town named Gravity, not to mention Hazard, Fearnot [!] and Ono[!].) But Elliott isn’t one who would follow the paths of expectations.

The piano trio configuration of MOPDtK—consisting of Ron Stabinsky on piano, Kevin Shea on Drums, and Elliott on bass—conforms to traditional jazz styles like the blues to lighten the listening experiences and to invite, rather than discourage, interest in the serious underlying themes.

Disasters Vol. I commences with no less than the subject of nuclear disaster. “Three-Mile Island” recalls the accident at the nuclear power plant south of Harrisburg that released radioactive gas and iodine into the atmosphere (after The China Syndrome, the movie that warned of such an event, opened in theaters). Stabinsky’s scurrying piano improvisation and treble-clef tinkling over the pulsating bass lines and electronic background effects evolve from growing industrial failure, as if with a mind of its own, to a carefree blues during which the warnings are ignored, like Saturday Night Live’s MacGruber skit. With similar dark humor, the track ends with an electronics-produced shiver and whoosh! Fortunately, no one perished from the real-life nuclear accident.

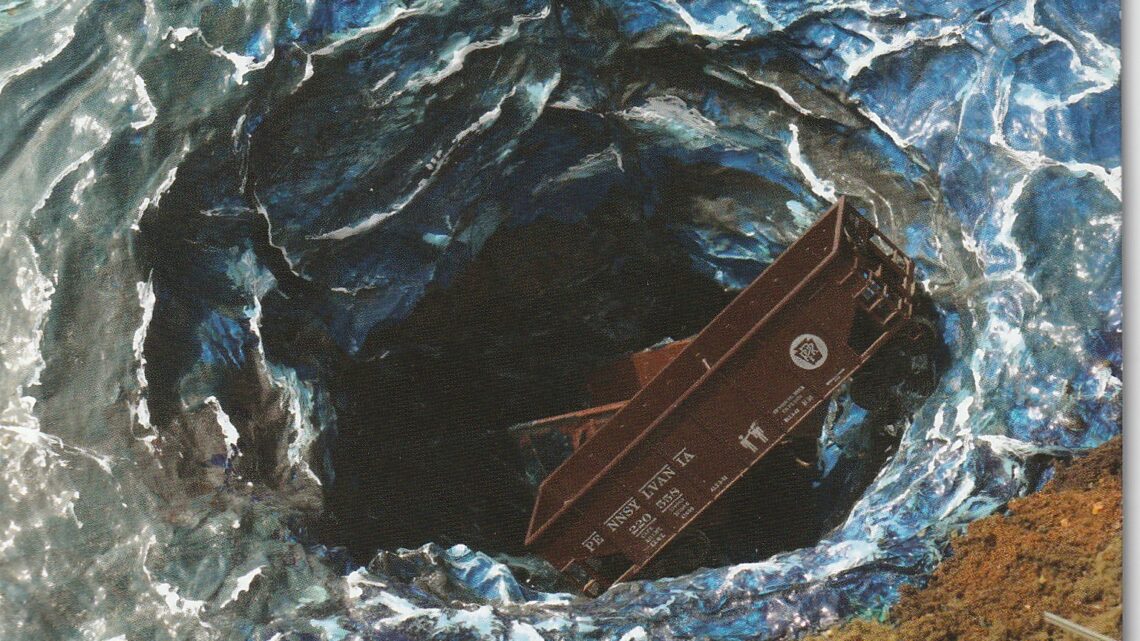

Mostly, Stabinsky and Elliott depict the Reading Railroad’s train wreck of May 1899 in “Exeter” with calming reassurance—indeed, over Elliott’s walking bass lines, as if the passengers were strolling instead of rolling into the Cannonball section of the train, where 29 passengers died. Initially, Elliott plays the melody until Stabinsky repeats the first two measures, after which the relaxing theme includes the piano’s tremolos and crescendos and darting accents. Suggestions of danger come from Shea’s rumbling drumming, contrasting with the ease of the theme, and from occasional Erie, ringing, whistling-falling-fireworks electronics.

What is Marcus Hook? Probably a reference to the February 1932 Bidwell oil tanker explosion killing 18 workers. Unfortunately, though, the city of Marcus Hook has experienced more than one disaster, including another in 1975 that killed two men and injured at least 23. Again, the trio puts the listener at ease with a slow, melodic performance that glides against expectations, both due to the jarring nature of the disaster and due to MOPDtK’s more freely improvised work on previous albums. Once more, Elliott begins the tracks by stating the melody, a bluesy one at that, over mostly standard major-key changes. Then Stabinsky comes in with controlled, underplayed command that evinces nary a shred of alarm that an explosion would cause. “Marcus Hook” is a dedication, instead of an attempt at re-enactment, up to the final single pianissimo notes.

MOPDtK performs “Wilkes-Barre” twice, once as the album’s third track and also as an alternate take at the end of the album. Possibly one of those tracks, if not both, refers to June 5, 1919 Baltimore Tunnel Mine explosion when a power cable ignited explosives taken into the mine (92 dead). Or, the alternate take, instead of repetition, may commemorate the loss of seven miners at the South Wilkes-Barre Colliery in May 1935 when a 250-pound boulder fell 600 feet through an ascending mine shaft elevator. The first “Wilkes-Barre,” though initially free, moves into a four-four swing, the acoustic piano trio breaking into a free-improvisation and then into a double-time middle section. The alternate take includes an electronic/acoustic call-and-response. Shea’s continuing shakeup of the rhythms throughout the album provides the scrambling undercurrents that contrast with the accessibility of the piano/bass melodic work based on traditional jazz forms.

“Centralia?” That unfortunate city exists no more because, with disastrous results, volunteer firefighters ignited a coal dump, creating a coal-seam mine fire extending over eight miles. It has been burning since 1962 and is projected to continue burning for two hundred more years. MOPDtK depicts this disaster with Altoona derisive romping that refers to the folly of humans. They caused an ecological disaster that claimed no lives but sickened the town’s residents, who had to move away. More lively than most of the other Disasters Vol. I performances, with Stabinsky’s roaring bass-clef upsweeps, “Centralia” is the toe-tapper of the album as the trio with brio musically describes disbelief at the unfortunate unintended consequences committed by the flummoxed but well-intentioned townspeople and the coal company’s irresponsible officials.

And then there’s the Great Johnstown Flood of 1889, during which 2209 lives were lost in the greatest loss of life to a FEMA-less U.S. disaster until that time. Man-made South Fork Dam broke and flooded Johnstown with 20 million tons of water from Lake Conemaugh. (This assumes that MOPDtK’s “Johnstown” probably doesn’t include successive floods, causing more townspeople to drown in 1936 and 1977). The introduction this time consists of high-pitched descending, echoing electronics before the trio enters with a medium-tempo jazz waltz, almost danceable with conventional Harmony but for Elliott’s springing bass lines and Shea’s stirring drum work. The piece ends for you’n’s with a somber rubato slowdown to an accented minor chord, splashed with a final droll electronic effect.

“Boyertown” was the site of an opera house fire where, during a literally disastrous performance, 175 people died when a stereopticon machine exploded and the stage curtain caught fire. The event receives Elliott’s bowed lumbering tango vamp over dramatic accents and pauses. Stabinsky lightly plays the tune with a spare single-noted delivery of the melody while Shea’s furious drumming suggests the Panic.

Yet more disaster occurred—not historically as a landmarked memory, but more recently with survivors living to tell about it—in the Pennsylvania town of Dimock, where an oil company didn’t repair gas wells leaking methane gas. The result was an exploding water well in January 2009, making the town’s water unfit to drink. Actually, water caught fire when poured from homes’ spigots. Yet again, MOPDtK doesn’t try to express musical outrage, but instead to create awareness of mostly other people causing illness and misery, if not doing the killing, through incompetence, inattention, and indifference. And “Dimock” consists of a densely chorded swing with repeated phrases at varied tempos.

Still, disasters continue. In Pennsylvania, as elsewhere. Elliott’s naming of MOPDtK’s most recent album as “Vol. I” suggests that there are more disasters that have killed to be commemorated.

Even as hurricanes, tornadoes, terrorism, automobile pileups, floods, shootings, mudslides, building collapses, blizzards, fires, war, tsunamis, train and plane crashes, and wildfires continue to contribute to the country’s history of disasters, Pennsylvania offers yet a few more of its own for consideration.

While the 1889 Johnstown flood is said to have involved the state’s greatest loss of life from a single event, illness and death from the influenza pandemic of 1918-1919 shouldn’t be forgotten. Certainly a disaster by any stretch of the imagination, the outbreak caused, until now, the country’s greatest loss of life. The flu spread across the state—and then across the United States—from the Philadelphia Navy Yard, although another epidemic source was Fort Devens, Massachusetts. Philadelphia was the city experiencing most of America’s fatalities from the flu—over 12,000—when the city became a hot spot for the epidemic after a British merchant ship docked there in 1918.

There was the 1948 Donora smog, when an air inversion caused the pollution from steel plants’ smokestacks to remain close to the ground, making it hard to see more than a few feet and causing the death of 22 victims from respiratory failure.

More recently, Pennsylvania experienced flight disasters too, including one near Pittsburgh where a crash in 1994 caused the loss of 132 lives.

But of course, the most famous airplane crash in Pennsylvania’s history occurred near Shanksville on September 11, 2001, when 40 passengers and crew members perished after they tried to overcome the terrorists who attempted to take command of the airplane.

How can the power of music provide scathing social commentary and yet compassionate remembrance related to disasters caused by human error, ignorance, or neglect; technological and/or industrial failure; accidents; or malice?

It’s Mostly Other People Do the Killing to the rescue!

Artist’s web site: www.moppaelliott.com

Label’s web site: www.hotcuprecords.com