A thought from Brian Landrus about his new album seems to be the point of conservation, humanitarianism, and/or altruism…and possibly, of human existence: “I need to be more aware of our world and the reason to be here—leaving something more than just taking.”

A politician’s more-profound-than-intended vituperative criticism of another politician recently reflected this sentiment: “He’s a taker, not a giver.”

In the end, is a person a taker or a giver? Are all musical performers givers due to their intentions to bring joy and/or comfort to listeners, sometimes at great sacrifice? Is a musician a giver if he or she becomes wealthy from their musical talents? Or is he or she both a giver and a taker? If so, what’s the percentage of his or her taking and giving? Does it matter?

Without getting into the moral implications of the question, obviously Dr. Brian Landrus is a giver. He has chosen to use music as a means of giving to achieve a higher level of paying forward.

He says so himself: “I plan on doing things that are much more important to the world than simply recording another album with great musicians.”

That he does.

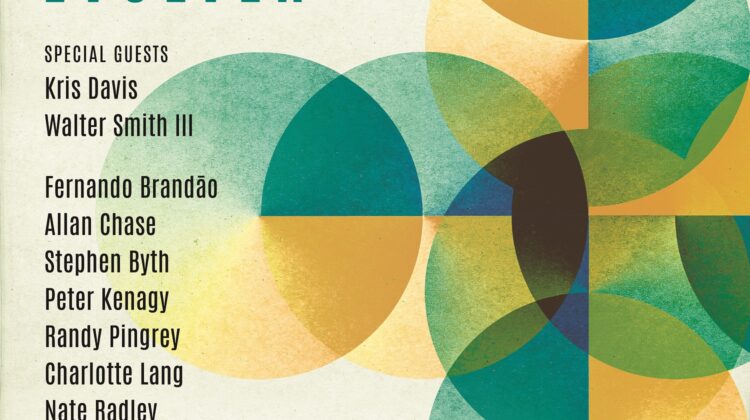

He does both on his most recent album, Red List: Music Dedicated to the Preservation of Our Endangered Species.

It’s gratifying to hear Landrus fulfill the promise of his early recordings to become one of his generation’s leading jazz musicians, having developed his own recognizable aesthetic approach on lower-register wind instruments and creating music with a higher purpose in mind.

What is the Red List? you might ask.

Founded in 1948 and based in Switzerland, the International Union for Conservation of Nature, a global authority on the natural world and how to protect it, created the Red List of Threatened Species™ (www.iucnredlist.org), used by global governmental agencies and environmental organizations, to determine the likelihood of extinction of the world’s species (now at 40,000 and counting). The IUCN’s Green List (https://iucngreenlist.org) measures and promotes conservation success.

Landrus shared his sense of environmental urgency by sending the participating musicians photos and descriptions of 13 animals facing extinction.

His mission brings all 13 to musical life.

Before the recording session started, he discussed with the musicians the intensity he wanted to convey to achieve listeners’ awareness.

The proceeds from the album help fund Save the Elephants (www.savetheelephants.org), whose name can serve as a rallying cry as well as a mission statement. Save the Elephants has already incorporated the album’s track of the same name in some of its campaigns.

Though he teaches music at Cal State in Sacramento, Landrus has recruited some of New York’s first-call musicians for his project, thereby making Red List—in addition to being an appealing environmental statement—a musical accomplishment in its own right as a continuation of Landrus’s effectiveness as an original composer.

Landrus starts Red List with “Canopy of Trees,” a medium-tempo piece of long melodic tones introduced by Geoffrey Keezer on Rhodes piano and driven by Rudy Royston’s drums as if going through an entrance. Additional voices like Landrus’s bass clarinet, Steve Roach’s trumpet, and Ryan Keberle’s trombone, calm and flowing, join with increasing volume along the way.

The longest track, “The Red List” (at ten minutes), enlivened by percussive agitation from John Hadfield and Lonnie Plaxico’s spirited bass lines, starts with a brief, softly played free-rhythm introduction. Then a burbling undercurrent animates Landrus’s extended, richly shaded baritone sax solo over the entire range of the instrument, recognizable as his own unique style from previous albums. Ron Blake—who has recorded his own memorable albums like Shayari and Sonic Tonic (and who records too infrequently)—brings another voice to the call for action, his solo wryly and slyly crafted from a spare start to a noticeable swelling of passion. “The Red List” ends with a rhythmless, contemplative, shimmering interchange of instruments fading out the piece’s repeating phrase.

The album’s shortest depiction, “Only Eight” (46 seconds) refers with dismay to the eight known remaining vaquitas, a porpoise native to Mexico’s Baja California. Perhaps the title should include italics and punctuation to evoke alarm, as in “Only Eight!” That is, what if there were only eight German shepherds or Siamese cats left in the world? Plaxico indicates his concern with an acoustic bass solo of precise pizzicato alacrity.

On the album’s second shortest track, “Mariana Dove” (57 seconds), Landrus depicts the flight of the Mariana fruit dove of the Mariana Islands and Guam with a bass clarinet solo. Landrus utilizes his absolute control of the instrument and technical dexterity to develop a sound, oddly enough slightly similar in tonality to an oboe, with repeated fluttering sonic descents.

And the third shortest musical description, “Giant Panda” (1:12 minutes), consists of a brief improvisation too as Landrus poignantly plays with a slight vibrato in the lower register of the bass clarinet, his fastidious attention to tone rising to cushioned conclusions of each phrase.

As for saving the elephants, “Save the Elephants,” dedicated to the endangered African elephant, establishes a jaunty rhythm of Plaxico’s electric bass, Hadfield’s percussion and Royston’s light drumming with a pronounced reggae-like backbeat. Keezer switching to organ, the composition proceeds, ironically, nimbly enough for a description of elephants, as if they trip the light fantastic, all the while projecting joy and wonder.

Beyond the personal expressions of improvised musical concern, Landrus’s composed pieces provide extended insight into his passion for the subject. “Nocturnal Flight” was written with the flightless nocturnal kākāpō in mind. Though it can live to be 100 years old, less than 200 of these parrots remain on island preserves of Whenua Hua and Anchor off the coast of New Zealand. Nir Felder comes in first with atmospheric acoustic guitar work over Plaxico’s whole notes on electric bass before the harmonized ensemble responds to Felder’s call. The piece increases in energy and blooming colors after the first chorus as the close harmonies densify. Keezer contributes a ringing and scampering and sweeping solo on acoustic piano before Andrus comes in, lightly, with his signature baritone sax sounds of slight wails and trills, deftly played even in the lower register.

“Tigris” begins with Felder again as only he and Royston create the invigorating gambol, quicker than “Nocturnal Flight’s” tempo. Afterward, Keezer, Plaxico and Royston set up the additional rhythmic intensity for inspiring solos, Landrus’s growling, alto saxophonist Jaleel Shaw’s spiritual, and Felder’s exciting before an intertwined improvised fade-out. Maybe “Tigris” is meant to be an ironic title. The Tigris and Euphrates Rivers being the so-called “cradle of civilization,” nonetheless, wars and civil unrest in the region that have captured the world’s attention have affected the livelihood of various species, such as the Iraqi eyelid gecko, the Basra reed warbler, and the Euphrates soft-shell turtle, which is almost as extinct now as the region’s Arabian ostrich.

“Upriver” refers to the gharial, a crocodile native to the rivers of northern India (its population reduced 96% from 5000-10,000 to 250 in 30 years). “Upriver” continues Landrus’s arranged blended harmonies with Ryan Keberle on trombone and Steve Roach on trumpet over Plaxico’s bounding electric bass patterns and Felder’s improvised electric guitar work in the background.

Landrus on alto flute and bass flute and Keberle establish a mellifluous coolness in a swaying, prodding three-four on “The Distant Deeps,” which brings in Corey King to sing Grammy-Award-winner (for the Broadway play Elmer Gantry) Herschel Garfein’s lyrics.

While “Only Eight” refers to the vaquitas’ reduction of population, perhaps Landrus meant it to be an indication of the potential for disaster for even more species, whose numbers are declining too. For he wrote another composition calling attention specifically to the vaquitas’ plight, entitled, with unmistakable directness, “Vaquita.” An evocation of the porpoise’s beauty and gracefulness, “Vaquita” features Landrus again on bass clarinet in the instrument’s highest and lowest registers, perhaps to create a visual image of the vaquita’s dives and rises to the surface. Shaw follows with his own impression of the vanishing species’ sleekness and its obvious worthiness of preservation.

Atmospheric with the octet’s (which includes Blake) free mixture of naturalistic sounds and onomatopoetic blend of animalistic tones, “Bwindi Forest” calls attention to the crisis of the forest’s mountain gorilla population that fell to 850 in Uganda’s Bwindi Impenetrable National Park, even though it’s protected within the park’s boundaries. Landrus opens the piece quietly with a low tone with vibrato on bass clarinet, followed by Keberle on the same note an octave higher, and then Blake adding to the growing harmony as if the sun were rising. With Keezer splashing upper-register interactivity on the Rhodes, the intensity grows, no rhythm included, as a sonic daily awakening. Remaining as silent observers are the park’s Brazzeia longipedicellata and brown mahogany plants, which too are becoming extinct.

But the news is not all bad.

The world’s most endangered feline species, the Iberian lynx, has grown from a population of 100 to 500, thanks to the European Union’s multi-million-dollar efforts to preserve it. A new state park in California, Dos Rios Ranch, helps save the Aleutian cackling goose from extinction. And the one-horned Indian rhino has increased its population in India and Nepal from 100 to 3,600 within the past few years, mostly during the pandemic, according to the International Rhino Foundation (https://rhinos.org), through the translocation of the rhinos from densely populated areas to the Manas National Park in Assam, for example.

Obviously, much more work is needed. Alas, Red List’s “Javan Rhino” track honors that species which now numbers only 67.

Brian Landrus’s Red List album is a valued and valuable musical project to raise awareness of the potential for extinction—and of the worldwide efforts of environmental groups like IUCN to study, understand and act to reverse declines and further the growth of threatened species.

Artist’s Web Site: brianlandrus.com

Label’s Web Site: https://www.palmetto-records.com