Most of us have come to know Frank Harrison as the pianist in Israeli saxophonist Gilad Atzmon’s Orient House Ensemble. Frank’s sensitive accompaniment stands out: he traces the rhythmic arc of Gilad’s middle-eastern and north African compositions with poise and elegance. As is the case with some of the best jazz instrumentalists, he is a fine storyteller.

On his most recent trio CD, Sideways (Linus, 2011), Frank reveals his considerable artistic depth, in a brace of originals and covers. Whether it’s the whirlwind swirling around Antonio Carlos Jobim’s Dindi, or the spacious and luminous treatment given to George Gershwin’s How Long Has This Been Going On, it’s clear that Frank Harrison is one of the UK’s unique pianistic voices.

I chatted with him recently about Sideways and about his influences and feelings about jazz in Britain.

John Stevenson: Sideways is your second CD as a leader since 2006’s well-received First Light (Basho). Do you prefer the trio format to other configurations? Is Linus the name of your own label?

Frank Harrison: For me the trio is the most open, exposed way of playing. That can be scary – if anyone is not completely in the moment, it’s very obvious – but it also makes the whole thing full of potential and allows for a lot of freedom. We never know what we’re going to play before we go on stage, but if the communication is open between everyone, the music just happens. Linus is my own label. I thought it’d be fun to put it out myself, and the fact that almost all sales these days are on gigs or online makes that an easy thing to do.

JS: Tell us about your sidemen: drummer Stephen Keogh and bassist Davide Petrocca? What specific qualities did they bring to the Sideways project?

FH: They’re both incredible musicians, with huge technique and musicality, but I’d say the biggest thing that they bring is openness. They give themselves completely to the music and play what needs to be played. But they’re not sidemen – we all have an equal role, and anyone can pull the music in any direction.

JS: You lend your signature treatment to the folk tune, The Riddle. I particularly like the way it segues rather unexpectedly into The Twelfth of Never, reminding me of Johnny Mathis’s memorable interpretation of the song. Do you find yourself especially drawn to the folk tradition?

FH: I got into British folk music a few years ago and stumbled across The Riddle Song, and just fell in love with the simplicity of it. For me there’s something very deep in those tunes. And I love that I don’t know what it is – the harmony and melodies are so simple that it’s hard to see where the magic is happening! I didn’t know about The Twelfth of Never until I Googled it, but it looks like Johnny Mathis (and Cliff Richard) also liked it and turned it into a cheesy 70s pop ballad.

JS: Dindi, for me the standout track of a sterling session, receives a particularly up-tempo treatment on the CD. Was this a fun tune to work out on?

FH: Yeah, we had a lot of fun with that. We didn’t rehearse it – we just had the idea in the studio to play it in a different tempo and time signature so hopefully we captured that feeling of finding something for the first time!

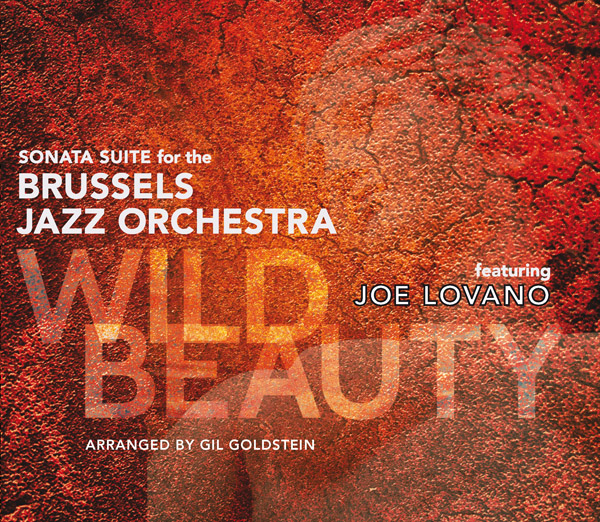

JS: Your work as a sensitive accompanist to jazz artists as diverse as reed players Tomasso Starace and Gilad Atzmon, as well as singer Tina May, already marks you out as a versatile pianist. Have you ever forayed into big band arranging and performance?

FH: Not since my school big band. I love big band music, and one day would love to do something in that setting, but for now I’m happy exploring what you can do with three or four instruments.

JS: When did you first become acquainted with and attracted to jazz?

FH: I was eleven and we took a cassette tape of Billie Holiday on a family holiday. I think it was on loop in the car, and it was the first time I’d really heard anything that swung. I liked the fact that there was a lot of logic, structure and pattern in it – but also a huge amount of freedom. When we got back I dug out some of my dad’s old LPs – some Ellington, Monk and Erroll Garner – and started trying to find those notes on the piano.

JS: Do you get tired of people making references to the compelling lyricism of Bill Evans in your work, or do you view him as a major influence?

FH: No, I’m very grateful for any comparisons like that! I’ve listened to Bill Evans pretty much consistently since I was fourteen, and he’s been a huge influence. I’m not too fussed about whether or not I have ‘my own sound’ – I just listen to a bunch of stuff and then play what comes out. And as I’ve listened to a lot of Bill, a lot of Bill probably does come out!

JS: How would you assess the state of jazz in Britain?

FH: There’s a lot of great music going on. I keep hearing new music that blows me away. But I’m not sure what’s going to happen to the scene itself. British audiences are great to play to, but they’re mostly the same people we were playing to ten years ago – you don’t see that many new young people coming in. I suspect that the internet will help to get this music to a new audience, but it’s all quite new and uncertain still.

JS: You have been associated for many years with Gilad Atzmon’s Orient House Ensemble. Given Gilad’s outspoken stances on issues, has your own politics been influenced by being in the OHE?

FH: I don’t think so. I love the music that Gilad writes and plays, and that’s why I’ve been playing with him for so long. But when it comes to politics, I often feel like I’ve only just got enough room in my head for the music!