By John Stevenson

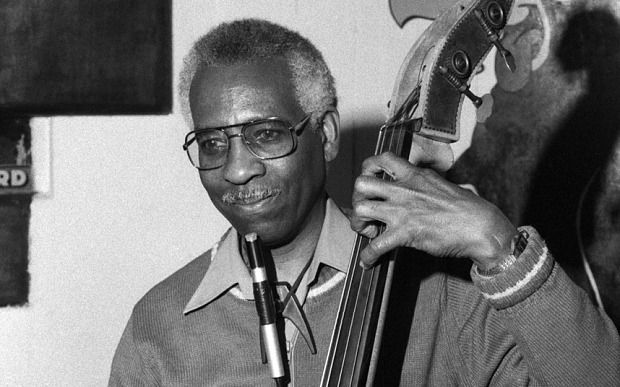

The double bassist Coleridge Goode, who has died aged 100, distinguished himself on the British jazz scene for more than 60 years, playing with some of the most innovative musicians of the postwar period.

Thanks to his finesse and sophistication, not to mention his technical gifts and singing ability, Goode was often in demand for recording sessions and live performances across Europe. He played on the original recording of Django Reinhardt’s jazz standard, Belleville, for the Decca label in 1946, on a date that also featured Stephane Grappelli on violin. He recorded with the pianist George Shearing and the drummer Ray Ellington as part of the Stephane Grappelli Quintet, and with the Tito Burns Sextet. He also featured in the band of the Jamaican alto saxophonist Joe Harriott, an experience he described as among the “greatest musical adventures of my life”.

Goode’s bass lines illuminated Harriott’s experimentations in free-form and hard-bop jazz on albums such as Southern Horizons and Free Form (both 1960), Abstract (1960), Movement (1963), and High Spirits (1964), on which he appeared alongside the Vincentian trumpet and flugelhorn player Shake Keane, the pianist Pat Smythe and the drummers Bobby Orr and Phil Seamen. He also worked extensively with the pianist Mike Garrick, contributing a fine vocal in the manner of Leroy “Slam” Stewart to The Lord’s Prayer on Garrick’s 1968 album, Jazz Praises.

Memories of church in Jamaica

Goode’s singing on that composition would undoubtedly have conjured up for him memories of growing up in the shadow of the church in the Caribbean, for he was born into a religious family in Kingston, Jamaica. His father, George, was a part-time choirmaster and organist at the St Michael’s and All Angels church in Kingston, and his mother, Hilda, sang in the Kingston parish choir. Thus the young Coleridge – he was named after the composer Samuel Coleridge-Taylor – grew up listening to the works of Handel and Bach.

From an early age he excelled at playing the violin, but he also nurtured a desire to become an electrical engineer, and left Jamaica in 1934 to attend Glasgow’s Royal Technical College (now the University of Strathclyde). From there he went on to obtain a degree in electrical engineering at the University of Glasgow.

From an early age he excelled at playing the violin, but he also nurtured a desire to become an electrical engineer, and left Jamaica in 1934 to attend Glasgow’s Royal Technical College (now the University of Strathclyde). From there he went on to obtain a degree in electrical engineering at the University of Glasgow.

Discovering jazz on the radio as a student, and falling under the sway of Walter Page, Count Basie’s bassist, Goode took up playing the bass and, to his parents’ disappointment, abandoned his ambitions of returning to the Caribbean as an engineer, choosing instead to become a professional musician. He moved to London in 1942, quickly establishing himself both in small Caribbean clubs and larger West End venues such as the Panama Club. He began to perform in groups with the pianist Dick Katz, the trumpeter Johnny Claes and the guitarist Lauderic Caton, swiftly progressing to recording sessions with some of the most exciting talents on the jazz scene.

Early use of the electric pickup

Besides Page, Goode had paid particularly close attention to the playing style of Slam Stewart, especially the way in which he plucked (or bowed) the strings of his double bass and the fact that he also sang – both facets that quickly became part of Goode’s approach. He was also an early pioneer of the use of an electric pickup to amplify his double bass, deploying it on one of his recordings with Grappelli in 1946.

Goode remained active in British jazz until his 90s, when he could still be seen playing in the house band at the drummer Laurie Morgan’s Sunday jam sessions at the King’s Head pub in Crouch End, north London.

In 2011 he was honoured at the All-Party Parliamentary Jazz Appreciation Group’s awards for services to jazz, and in 2014 he celebrated his 100th birthday at a special performance organised for him as part of the annual London Jazz Festival.

His wife, Gertrude, died in June at the age of 96. He is survived by their daughter, Sandy, and son, James.

Coleridge George Emerson Goode, musician, born 29 November 1914; died 2 October 2015