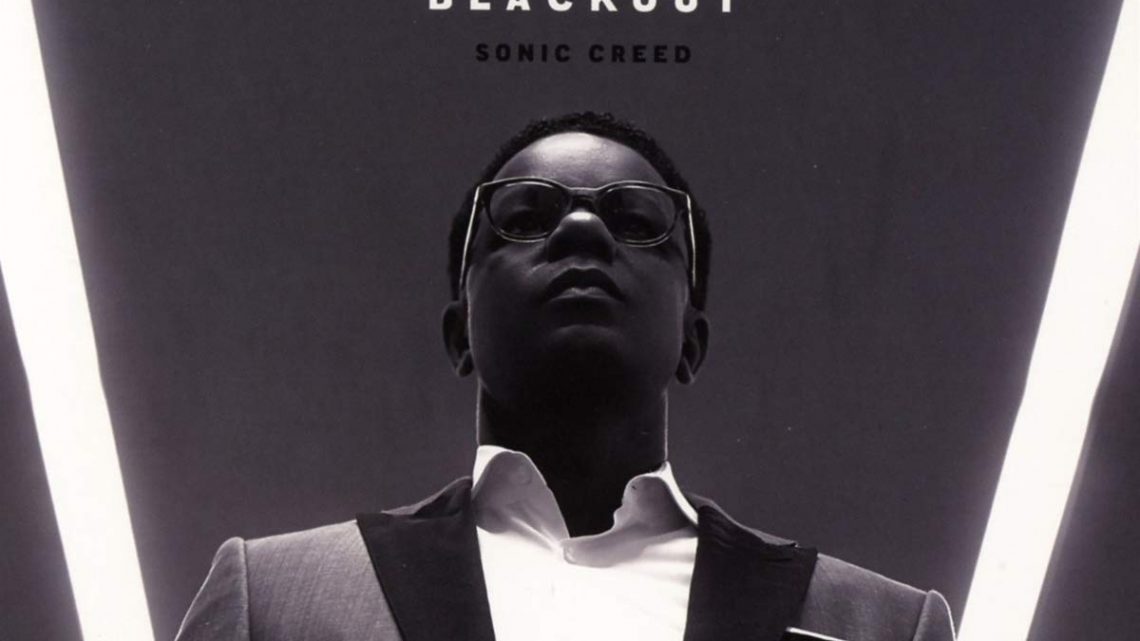

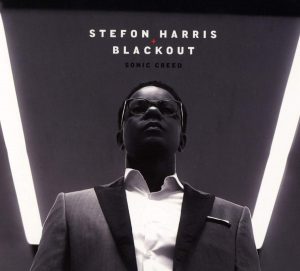

Stefon Harris’ Blackout has proven to be an enduring concept, and Harris has grown to be an enduring presence in the international jazz scene.

The title of Blackout’s first album, 2004’s Evolution, proved be prophetic, even if its original meaning intended a broader perspective. For Blackout has evolved through the years. In 2018, its most recent release, Sonic Creed, reaffirms the group’s commitment to legacy and progress. Several members have been added since the group’s start. Harris adds on Sonic Creed an explorative pianist, James Francies, who soon will be releasing his own first album, Flight. As yet another example of evolution, the contributions of guitarist Mike Moreno have enhanced the sonic textures of the group. But Blackout endures, even as it evolves, because the deeply rooted wisdom of it vision endures.

In the twenty years since he released his first album, A Cloud of Red Dust, Harris has developed—album by album, concert by concert, classroom by classroom, teaching app by teaching app, speaking engagement by speaking engagement, award by award—into a worthy successor of the ground-breaking jazz artists who preceded him. The release of Sonic Creed reveals a more sustained singing sound, more sentiment, the influence of more musical genres like hip-hop, and more melodic interest, although A Cloud of Red Dust did contain the melodic beauty of “In the Garden of Thought” and the sentiment of Bobby Hutcherson’s “For You Mom & Dad.”

In the twenty years since he released his first album, A Cloud of Red Dust, Harris has developed—album by album, concert by concert, classroom by classroom, teaching app by teaching app, speaking engagement by speaking engagement, award by award—into a worthy successor of the ground-breaking jazz artists who preceded him. The release of Sonic Creed reveals a more sustained singing sound, more sentiment, the influence of more musical genres like hip-hop, and more melodic interest, although A Cloud of Red Dust did contain the melodic beauty of “In the Garden of Thought” and the sentiment of Bobby Hutcherson’s “For You Mom & Dad.”

Harris’ Blackout albums have paid tribute to the forebears by starting each album with a jazz classic—those classics being Don Grolnick’s “Nothing Personal” on Evolution, George and Ira Gershwin’s “Gone” on Urbanus, and, now, Bobby Timmons/Oscar Brown’s “Dat Dere” on Sonic Creed.

Blackout’s consistent musical intimation of indebtedness to one’s predecessors suggests that the development of jazz has continued to this point because the jazz explorers of previous generations have built the pyramid-like foundations of this American genre. Those introductory songs on Blackout’s albums serve as a reminder of their influence on today’s music, even though they are rearranged.

Harris has developed his own guide to recording which incorporates common sense, but which is ignored too often: “If I don’t record this music, will the sound of this music exist in the world? If the answer is no, then we have to go to the studio.” Exactly. The same standard could apply to spoken, written, painted or danced expression as well. Why repeat what has been done before? Authenticity of thought and feeling guide Blackout as its members interpret in their own voices their previous generation’s music.

And so, from the beginning, it’s clear that, while honoring The Big Beat’s Art Blakey & The Jazz Messengers, Blackout updates “Dat Dere” with its own reflections upon its universality of human experience in the new millennium. For “Dat Dere” starts, not with the powerhouse force of Blakey, but with the subtle percussiveness of Pedrito Martinez and Moreno’s signature descending guitar line. Drummer Terreon Gully, who has remained with Blackout through the years, holds together the sonic mixture, along with bassist Joshua Crumbly’s two-beat vamp. Similarly, “The Cape Verdean Blues” contains Horace Silver’s irresistible enthusiasm, an indelible part in his spiritual legacy, but with different voicings, unexpected instrumentation and rhythmic alterations. Bass clarinetist Felix Peikli and Francies start with a call and response before flutist Elena Pinderhughes takes over the melody, which is subject to pauses, elongation of phrases and quickened repeats. Saxophonist Casey Benjamin, who rejoins Blackout from Urbanus, splits the track in two parts with his extended, free-rhythm improvisation. Harris’ final flurried choruses bring more joy to the track before Gully’s exhilarating conclusion framed by the final “The Cape Verdean Blues” phrase, repeated between dramatic quarter-note accents.

Sonic Creed features some new compositions consistent with its theme of the black heritage and familial continuity. Harris’ own contributions sing on the vibraphone of his wife and his sons. On “Let’s Take a Trip to the Sky,” Jean Baylor takes the song’s sentiment to heart as she freely interprets the song’s melody with its slowly enveloping soulfulness, made more effective when Baylor emphasis goes high when she sings the word “high” or by singing the title with emotional deliberation. “Chasin’ Kendall” builds from a bass line that Harris developed, as he added Benjamin’s easily flowing melodic line, Martinez’s light percussiveness and Peikli’s low-key bass clarinet solo effectively to capture the listener’s affection, its effectiveness no doubt due to its origins from Harris’s affinity for the singers of his childhood like Donny Hathaway. Lasean Keith Brown contributed “Song of Samson,” a pulsating piece whose Latin rhythm, heightened again by Martinez’s extended intensifying solo, animates Harris into joyous improvisation on marimba.

Still, in contrast to Urbanus, which contained all original compositions except for “Gone,” Sonic Creed continues to cover more songs by important jazz artists. There’s Wayne Shorter’s “Go,” structured over Moreno’s continuing motive. With Benjamin’s infectious work on vocoder and Harris’ on marimba, it’s funkier and more danceable, despite its unconventional rhythmic structure.

A constant presence in Harris’ life and music, Bobby Hutcherson, whom Harris replaced in the SFJAZZ Collective, is more than remembered. Hutcherson is cherished. Fittingly, his jewel of a composition, “Now,” is included in Sonic Creed. Built upon a repeated melody of rising and falling notes, “Now” attains increasing meaning and feeling with each chorus, particularly with the slowed, shimmering ending phrase that allows for its prismatic sonic spectrum to sink in. Baylor infuses the arrangement with a spiritual grace as she layers her vocals in a gorgeous atmospheric outpouring of emotion.

Abbey Lincoln, cherished for her positive, no-nonsense spirit, is represented by yet another emotional, and again melodic, interpretation, this time of “Throw It Away.” As before, Harris peels down the music of Sonic Creed to its essential core by following the feeling of the song, even though his earlier albums documented his reserves of seemingly boundless technique available for freer jazz or post-bop. Always truthful in her life and in her music, Lincoln’s words in the song recall her fearless and gentle honesty: “Throw it away / Give your love, live your life / Each and every day.” Drummer Terreon Gully suggested a path to the soulfulness of Lincoln by recording the song in literally a blackout environment with no lights at all in the Systems Two Studios, as if in séance. What you hear is the first take, distinguished by Benjamin’s intensely felt soprano sax solo.

Unexpectedly to many, Harris and rising-star vibraphonist Joseph Doubleday describe in a musical duo the immensity of the loss of Michael Jackson as a non-categorical musical figure admired by multitudes, including by jazz artists—as are, for example, using Michael Jackson’s tribute to Ryan White as a means for a remembrance of Jackson himself—and as a representation of Harris’ Sonic Creed of family, community and legacy. Remembering the ancestors who made us who we are today and, as part of the sonic creed, whose standards we strive to live up to, Doubleday’s and Harris’ malleted instruments sing: “Like a shooting star, flying across the room / So fast, so far / You were gone too soon / You’re part of me and I’ll never be the same / Here without you / You were gone too soon.”

Artist: www.stefonharris.com

Label: www.motema.com