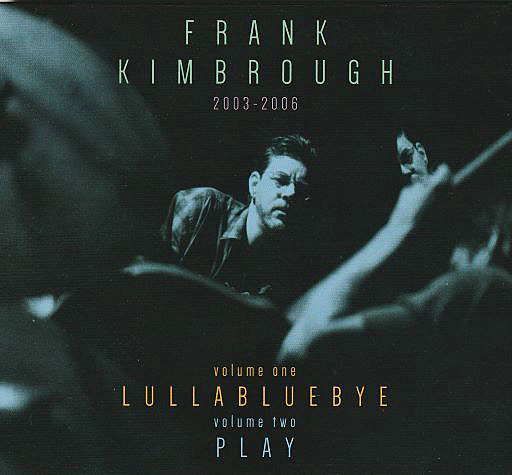

The outpouring of tributes, the results of surprise, disbelief, and grief, occurred soon after Frank Kimbrough’s unexpected passing at the age of 64 in December, 2020. Kimbrough’s unique combination of personal and musical characteristics endeared him not only within the New York jazz community, but also with his listeners and his students at The Juilliard School. Generous and self-effacing, but dedicated and innovative, Kimbrough developed a complex style of eloquence with passionate undercurrents that represented a standard of artistic freedom. His versatility, his in-the-moment immersion in a performance, and his perceptible joy derived from the art of music elevated groups with whom he performed. Kimbrough was okay with his relative lack of name recognition among the broad listening audiences. Often, his individuality was subsumed in the larger vision of the groups in which he performed. Music was more important than fame.

In commemoration to Kimbrough, Palmetto Records producer Matt Balitsaris has re-released in one package two of the pianist’s highly praised Palmetto albums, Lullabluebye and Play. Balitsaris decided to remix and remaster the albums, giving the instruments equal sonic weight within the interactivities of both trios. The results more effectively include the give-and-takes that occurred throughout the two sessions, raising them to the upper echelon of free improvisation associated with legendary his in-the-moment immersion in a performance, and perceptible joy derived from the art of music piano his in-the-moment immersion in a performance, and perceptible joy derived from the art of music trios. Kimbrough’s objective for both albums was to write compositions and perform in ways that highlighted the contributions of the groups’ other musicians. That objective can be more clearly heard now on 2003-2006.

Perceptively, Balitsaris noticed the unmistakable camaraderie within the trio of Kimbrough, bassist Ben Allison, and drummer Matt Wilson on the “Karna Kangi” track of The Herbie Nichols Project’s album, Strange City (which included a septet on most of the tracks). The fact that Nichols never recorded this composition of his own allowed the trio to interpret it freely and imaginatively with quirkiness, humor, and respect.

On their first trio recording, Lullabluebye, Kimbrough was consistent with his risk-taking by recording with no rehearsals—a method with which he became identified for allowing music to stream from within. Allison and Wilson inherently sensing Kimbrough’s playfulness within the music, the like-minded musicians were more than ready to record as a trio, as Balitsaris recommended. Indeed, “Kid Stuff” on Lullabluebye celebrates their youthful approach to music as a source of joy. Their feeling of carefree play suggests carefree contentment reminiscent of the spirit of childhood discovery associated with Vince Guaraldi’s Charlie Brown recordings.

The title track of Lullabluebye confirms that Kimbrough’s confident, spare, and soulful style was already formed before this recording. Perhaps it was influenced by his experiences with Shirley Horn in Washington D.C., whose style is similarly relaxed and individualistic. Never one for flashy technical displays or extreme contrasts of volume, Kimbrough performs “Lullabluebye,” his composition of 22 measures, with wry allusions to the blues calmly within the piano’s middle and second treble octaves. The trio’s sharing of in-the-moment release of ideas arise from Kimbrough’s framework of a loose melody as he sprinkles notes hither and thither or staggers phrases with mischievous discovery, allowing Allison and Wilson to go in any direction they desire while improvising, a gem being crystallized.

“Ode” honors one of Kimbrough’s influences, Andrew Hill, with deferential freeness of rhythm that leads Allison and Wilson, who are ready for any thought that Kimbrough releases from his imagination. Of interest are the looseness and changes that became associated with Kimbrough and remained even in his later albums like Solstice, released in 2016. The lack of confinement to strict musical rhythms or melodies is the highlight of “Whirl,” which starts with a scramble of piano and drums, running and pausing, running and pausing, running and pausing. Kimbrough moves into tonal dots and sprinkled tones and sporadic abrupt treble-clef waterfalls and then waterspouts after Allison’s and Wilson’s energetic solos of rhythmic elasticity. Hints of Thelonious Monk’s influence (which led to Kimbrough’s recording of 70 of Monk’s compositions on six CD’s in the Monk’s Dreams package) emerge from frolicking crescendos and the final Monk-like chord.

Kimbrough’s mood takes a reflective turn on “Ghost Dance,” an investigation into the nature of beauty with haunting spirituality, quietly expressed by mysterious minor-key harmonies awaiting resolution. In fact, Kimbrough’s aesthetic appears to be driven by and arises from the appreciation of musical purity, as noted by Carl Allen, who hired him to teach at The Julliard School, where Kimbrough mentored students like Immanuel Wilkins and Micah Thomas. Wilkins revealed that sometimes, for 12 hours, Kimbrough would keep playing the same composition in a room at the school as he searched for perfection.

Kimbrough adapts the only standard on Lullabluebye, “You Only Live Twice” in F,

to his own unique style, as he does within any musical environment, including the blues, swing, free jazz, standards, or orchestral participation. Having been a member of The Maria Schneider Jazz Orchestra since her 1995 Coming About album. Kimbrough’s involvement in her orchestra seemed especially appropriate as a meeting of the minds for Kimbrough’s ability instantaneously to heighten the shifting emotional content of her compositions. But on Lullabluebye, the trio is relaxed and enjoying each moment, getting a kick out of the James Bond connotations conjured up by the song. And now the song title has acquired an ironic quality on the 2003-2006 re-release. Kimbrough lightly presents and deconstructs the song from Allison’s bounding bass lines and Wilson’s light undercurrent of steady rhythmic support, transforming the song from an intimation of danger to a medium-tempo breezy interpretation in a brighter mode than some of the pensive pieces on the album.

Allison’s “Ben’s Tune,” previously performed live but not recorded before Lullabluebye, is the only composition on the album that Kimbrough didn’t write. Its relaxed rhythmic bounce fits into the mood of the session of unruffled artistic chemistry and unrehearsed development of whatever thoughts cross their minds.

And speaking of lack of rehearsal, which Kimbrough valued for the extemporaneous expression that ensues, Lullabluebye’s last track, “Eventualities,” intentionally sets up the entirely natural improvisation, the result of close listening. Allison’s unplanned bass lines branching from a G root suggest the piece’s chord changes as Kimbrough and Wilson embellish Allison’s notes for a incomparable performance.

Play, the other album included in the 2003-2006 package, came into being from Kimbrough’s persistence to record an album with bassist Masa Kamaguchi and legendary drummer Paul Motian. His persistence prevailed even though Motian didn’t want to leave New York City to record in Palmetto’s studio in Pennsylvania. Motian finally agreed to be driven to and from the studio for five hours of recording that resulted in Play, an album named after Motian’s composition of the same name. Play proves how insightful Kimbrough could be about intriguing combinations of musicians, in this case of Motian and Kamaguchi during their first experience of performing together. Furthermore, Play documents Kimbrough’s first collaboration with Motian. Kimbrough insisted on a natural recording environment with the musicians playing near each other without headphones. Kimbrough and Motian were on the same virtual page, so to speak, when both decided to perform without written music after Kimbrough’s single run-through before recording. Pure, instantaneous improvisation, never to be repeated in exactly the same way again, was their goal.

And Kimbrough was correct. The trio is entirely distinctive, incomparable, with its own immediately created sound.

Legions of jazz listeners are familiar with Motian’s work, including his unforgettable work with jazz trios like those of Bill Evans, Keith Jarrett, and Paul Bley. However, the intriguing component of this trio is the lesser-known Kamaguchi, who performs with a personal, responsive style of fascinating note choices and clarity of tone over the instrument’s entire range. On Kimbrough’s slow modal composition, “Waiting in Santander,” featuring Kimbrough’s typical pulchritudinous reflective sound, Kamaguchi follows the pianist’s lead with occasional low-register anchoring notes at the beginning of phrases and then, with exact precision of intonation, melodic upper-register plucking for accents or rippling elaborations. Admired by Schneider, “Waiting in Santander” does recall Kimbrough’s individualistic contributions to her orchestra, particularly the trust in other musicians to take freely expressed risks for surprising and gratifying results, as encouraged by Kimbrough.

Perhaps as indications of Kimbrough’s enjoyment of the interplay with Kamaguchi, there are two more duo piano/bass performances on Play: “Beginning 2” and “Regeneration.” “Beginning 2” recalls Kimbrough and Kamaguchi’s performance on the 2009 Rumors album and on the posthumous 2021 Ancestors album. Ethereal, as are many of Kimbrough’s slower works (including the entire 2016 Solstice album…which, by the way, includes Motian’s “The Sunflower”), “Beginnings” is, as Duke Ellington would say, “beyond category,” investigating the nature of grace and revelations of beauty with Kimbrough’s introspective style. With the addition of drums on the first track, Motian adds soft rustling textures. “Regeneration,” written to instill hope days after the 9/11 attacks, presents an approach of broken and blocked chords rather than the single-note improvisation of “Beginnings.” Kamaguchi’s simultaneous rising quarter notes or inspired phrases gorgeously complement the chiming descending treble-clef chords.

However, the distinguishing elements of this trio—and the main reason for the recording of Play, as indicated by using Motian’s composition for the album’s title—happen when the drums embellish the tracks. “Play,” contrary to expectations suggested by the name, is a slow, quietly expressive, characteristically ruminative piece that leaves space for whole notes to ring while Motian and Kamaguchi fill in the calm sustains. In contrast, Kimbrough’s “Little Big Man” in F, composed of a three-phrase melody, provides opportunities for the trio to let loose with faster trading of ideas as they occur.

The spirit of Motian’s “Conception Vessel,” from his first ECM album, is set up by his initial solo before moving into, as always, an unrehearsed, liberated section that features the strengths of the members through extended solos. Balitsaris’s success in equalizing and clarifying the sounds of all three instruments in the reissue is particularly noticeable. Kimbrough’s “Jimmy G,” a luxuriant slow blues waltz also on Ancestors, honors Jimmy Giuffre, whose Jimmy Giuffre 3 albums served as an inspiration for the pianist, particularly those with Bley and bassist Steve Swallow. “The Spins” is a less traditional waltz, ignoring bar lines in the initial melody, before evolving into improvisations over a more defined meter of three, though still with Motian’s stirring rhythms. “Lucent” captures the spirit of productivity and dedication of Jim Luce, jazz recording engineer and producer, with a repetition of a phrase over different tonal centers.

Many musicians were affected by Kimbrough’s intuitive, explorative, honest style, both in music and in life. He established his style, perhaps during childhood in his native North Carolina, the home state as well of Thelonious Monk, John Coltrane, Max Roach, and Nina Simone. His students at Juilliard remember his sincere concern for their musical development and overall happiness as they walked with him and talked. They remember Kimbrough’s pithy nuggets of wisdom like “I don’t practice; music is my practice” or “rhythm is melody and melody is rhythm” or “get the [earbuds] out of your ears; listen to life; music is everywhere.”

And when drummer Jeff Cosgrove had told Kimbrough that he planned to record his music, Kimbrough replied with typical modesty, “Do it once I’m gone. Maybe then someone will want to listen to it.”

Well, people did—and do—want to listen to Kimbrough’s music.

Maybe Cosgrove, having recorded Conversations with Owls with Kimbrough, will release the album he planned. Cosgrove does play on two of the tracks, “Reluctance” and “Air,” on Kimbrough, a comprehensive commemorative album of 61 of Kimbrough’s compositions.

The sonically enhanced re-release of Lullabluebye and Play helps appreciate anew Kimbrough’s music and reinforces the importance of one of the true originals of jazz.

You’ll want to listen to it.

Artists’ Web Site: https://www.juilliard.edu/news/148001/frank-kimbrough-1956-2020-memoriam

Label’s Web Site: https://www.palmetto-records.com