Ryan Truesdell mentions in the liners notes for Lines of Color that Gil Evans had a reputation for taking his time while he composed or arranged. Perhaps that’s why the jazz that that Evans created has endured. Evans was meditative and obviously meticulous. For how else could he have created such beauty with an arranging style that had never before been considered? Like anyone else, Evans was a influenced by his experiences and by others’ ideas. Accordingly, Evans combined the muted atmospheric style of Claude Thornhill with the contemporary excitement of bebop and the conventions of big band singers and instrumental soloists. In addition, Evans obtained ideas from other sources, including those borrowed from classical music or Spanish composers. And so, he set up a method that still captures not just the attention, but also the hearts, of listeners. Proof of the continuing fascination with Evans’s music is his influence upon the current generations of composer/arrangers, most notably Maria Schneider. In essence, Evans changed the way that the music of jazz orchestras was arranged.

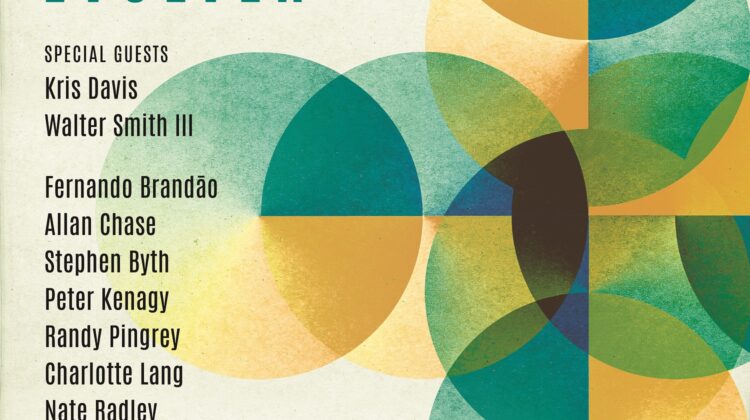

A diligent scholar of Evans’s music, Truesdell has researched and made available, often for the first time, some previously non-recorded Evans arrangements. As a result, over a short period of time, Truesdell has become recognized as yet another major arranger carrying on the Gil Evans tradition. First, Truesdell released on the ArtistShare Centennial: Newly Discovered Works of Gil Evans, coincidentally during the hundredth year since Evans’s birth. With the decline or consolidation of major traditional labels, ArtistShare, founded by Brian Camelio, allows for devoted jazz enthusiasts to fund through their own contributions recordings by such artists as Schneider, Danilo Pérez, the Clayton brothers and Robin Eubanks. Now, Blue Note Records has joined forces with ArtistShare for joint projects, including Lines of Color.

Truesdell’s title for his second album of Evans’s arrangements, performed by a band of jazz musicians of the millennium, is entirely appropriate. Evans was more interested in instrumental lines, sometimes in harmony, sometimes ascending, sometimes crisscrossing, sometimes descending, sometimes leaping, sometimes intersecting and sometimes stretching across bar lines, than in percussive four-beat regularity. His instrumentation and style lent themselves to blossoming colors that seem to grow organically from a single bud of a concept into complex subtleties, some of which continue to fascinate or to be discovered.

It turns out that Truesdell’s passion for, and study of, Evans’s works have led to an annual engagement at the Jazz Standard in New York, and this is where Lines of Color was recorded along with the appreciative applause of fans who got to hear some Evans arrangements for the first time.

Though Truesdell studied, sometimes restored, and prepared 42 Evans arrangements, which were heard throughout the week at the Jazz Standard, he winnowed those to eleven for Lines of Color. The theme for the selection was a concentration on works representing the entire length of Evans’s career.

What a thrill that must have been! Not only for Truesdell, who is completely dedicated to discovering every nuance of Evans’s music. But also for the musicians, who got to present some of Evans’s arrangements to a new generation of listeners, the musicians being aware of the fact that those arrangements hadn’t been performed previously by Evans’s famous contemporaries. And for the listeners too, who were treated to a first-time event that now, thanks to ArtistShare, other listeners can enjoy as well.

Like Evans, Truesdell generously allows room within the gorgeous lines and colors for individual soloists to improvise and to claim segments of the arrangements as their own. Lines of Color includes two such arrangements. The recording of “Greensleeves” substitutes trombonist Marshall Gilkes’ for Kenny Burrell’s performance of the song on Burrell’s Guitar Forms album. And then, Bix Biederbecke’s “Davenport Blues” allows trumpeter Mat Jodrell not only to make the piece his own, but also provides him the opportunity to perform over a newly discovered section of Evans’s original arrangement that Truesdell restored.

Singer Wendy Gilles, another of the band’s committed regular performers, brings to life several pieces with Truesdell’s usual devotion to the original compositions. Fairly straightforward without embellishment, Gilles assumes the role of big band singer for Evans’s 1940’s arrangements, which contain lyrics like “jumpin’ and jivin’” on “Sunday Drivin’” (on which the “g” is coolly dropped).

But Gilles also contributes to one of the most effective and gorgeous arrangements on Lines of Color, the “Easy Living Medley” (“g” in the title restored), arranged in 1947 for the Claude Thornhill Orchestra. It seems that the medley was misnamed because the memorable, and lengthiest, song of the three is “Moon Dreams.” Truesdell studied Evans’s methods extensively, and he understands his intricacies of harmony and complexities of style, as well as his musical influences, such as Ravel and Prokofiev. However, for the listener who merely lets the music wash over him or her, the beauty of the medley resides in the way it gradually unfolds, as do many of Evans’s arrangements. During the first 2-1/2 minutes of “Easy Living,” the song, Frank Kimbrough’s single-note piano solo, without his own chords or even the slightest deviation from the melody or any hints of improvisation, commences inauspiciously, though slyly when Evans inserts reed-driven counter melodies, borrowing a snippet from “Stars Fell on Alabama” and other brief references. At the end of “Easy Living,” the band swells with another full-spectrum richness, first employed at “Easy Living’s” bridge, to introduce Gilles’s presentation of “Everything Happens to Me.” With a sweet, declarative voice, Gilles assumes the role of the big band singer. The traditional format continues of an opening dance band chorus, with hints of influences from the danzón form, before a step-up-to-the-mic singer takes over—a format that was familiar to, and often expected from, listeners in that decade. But then the band glides into unknown territory with “Moon Beams.” If it sounds familiar, that’s because Evans’s Thornhill arrangement was a predecessor of its inclusion on Miles Davis’s immensely influential Birth of the Cool album. The full revelation of the arrangement happens after Scott Robinson’s intermittent saxophone solos, when Evans expands the scope of the arrangement beyond the familiar. That’s when its broad-ranging beauty, with flutes above french horns, trombones, baritone sax, bass clarinet and tuba, is released as all of the preceding elements of the arrangement come together in a thrilling finish—one that was never implied at the traditional beginning of the piece.

Lines of Color not only expands upon the recordings of Gil Evans’s arrangements, but also it expands upon the catalog of available Evans works that in some cases had remained unknown. In the case of “Davenport Blues,” Truesdell even restored an erased section of the arrangement through high-resolution tools previously unavailable. With at least 31 more available arrangements heard during the week of May 13, 2014, at the Jazz Standard, Gil Evans enthusiasts may hope for even more album releases in the near future.

2015

Label’s site: www.gilevansproject.com