Is that Jack McDuff playing?

No, it’s Alberto Marsico.

Marsico, a native of Turin, Italy, has been deeply influenced by McDuff’s sound, so much so that he attended one of McDuff’s week-long workshops in 1994.

Marsico’s passion for jazz was the cause for his recent friendship with fellow musician, Jeremy Monteiro, when Marsico was touring in Singapore, Monteiro’s native country. Marsico’s serendipitous request for assistance in finding a Hammond B3 in Singapore led to ensuing joint performances and their intention to collaborate on a recording.

That intention has resulted in the release of Jazz-Blues Brothers, which now, in 2021, is available in North America after being released in other countries in 2014. The album documents their ebullient work together, even as one track, “Wishy-Washy” includes a later sax dub in Singapore and a guitar dub from Hong Kong.

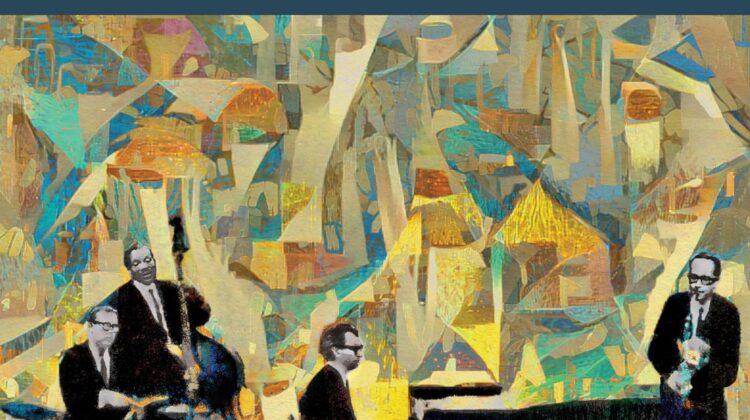

The instrumental composition of the Monteiro/Marsico group on their album comprises that of the traditional B3 quartet, with an organist, a tenor saxophonist, a guitarist and a drummer. But the keyboardists’ mutual respect, and their desire to record together, provide the give-and-take of Montiero’s piano as an another enthusiastic ingredient to the energetic groove throughout the album.

None of the tracks is more McDuffian than “Jack-Pot,” which Marsico wrote for McDuff when he was in Milan in 1991 and which became the title track of McDuff’s Red Records album. Now it’s Marsico playing the B3 in remembrance of McDuff with the signature chords, draw bar choices, volume control, soulful improvisational lines, and strolling pedal work. But then Monteiro joins in, and the infectiousness of “Jack-Pot” rises with his joyful piano solo, more in line with the exuberant build-up’s characteristic of Gene Harris—from single-line treble-clef improvisation to electrifying rolling crescendos and fully chorded attacks that diminish at the end of his solo to make the way for Marsico to create his own exciting B3 build-up too.

Jazz-Blues Brothers opens with a blues called “Opening Act” that provides the opportunity for each member of the quintet to establish their own personalities that carry through the album, always groove-oriented with the listener in mind as they create with the ease of seasoned musicians an irresistible sense of swing.

The soulfulness continues with Monteiro’s composition, “Olympia,” based upon a “All Blues” vamp over which the pianist overlays a faster melody for contrasting tension. Inspired by the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics before Monteiro recorded it with Ernie Watts, “Olympia” crackles with electrifying surges, due in no small part to the propulsion of Shawn Kelley’s drumming as guitarist Eugene Pao inserts subtle boogaloo riffs or Monteiro accompanies with blues-based block chords.

The groove continues at a slower tempo with Marsico’s poignant tribute to singer Lou Rawls, simply named “Lou.” Saxophonist Shawn Letts expresses the band members’ respect for Rawls’ talent with his extended spiritual statement inspired by gospel music, which, after all, was the source of the organ’s capacity for devotional expression in jazz. Monteiro contributes a powerful piano solo consisting of broad gospel-inspired chords of growing dynamic force, followed by Pao, the intensity of whose solo matches Monteiro’s. Marsico concludes the track with rousing, growling and exciting organ work that would leave an audience, or a congregation, standing.

In contrast to “Lou,” “Mount Olive,” which Monteiro wrote after visiting the Mount Olive Baptist Church in Washington, D.C., takes a joyous hand-clapping approach. The group’s cohesion and singularity of purpose, in evidence on all the tracks, comes through on “Mount Olive” as the quintet joins as one to express sheer joy in ways that words can’t.

But Jazz-Blues Brothers includes words as well.

Blues singer Miz Dee Logwood from Oakland, California performs with the group in the Elgar Room at Royal Albert Hall in London. Logwood belts out songs with such raw emotion, ease in front of an audience, vocal power and natural talent that she deserves wide recognition beyond her home in northern California.

Chosen no doubt because of its crowd-pleasing appeal with its humorous lyrics and its mnemonically accented (well, blues-shouted) “Drink! Drink!” Eddie Miller’s “I’d Rather Drink Muddy Water” provides a perfect showcase for the group’s, and her, talents. Probably not coincidentally, the song was often associated with Rawls after he sang it with the Les McCann trio on Rawls’ first album, Stormy Monday. Jazz-Blues Brothers includes another hyperbolic “rather” song when Logwood sings, this time, that she would “rather go blind / Than see you walk away from me, child.” This version of “I’d Rather Go Blind,” introduced by Etta James in 1967, involves a slow soulful outpouring of emotion from the heart roughly equivalent to the show-stopping force of Dreamgirls’ “And I Am Telling You (I’m Not Going),” but with the addition of Marsico’s gospel-tinged gospel voicings on organ.

Natives of countries from separate parts of the world, jazz and blues united this Monteiro/Marsico group, as well as Logwood, for shared excitement that infuses the music that they share on their album, now recently released in North America.

Artists’ web sites: jeremymonteiro.com; albertomarsico.it