Audacious.

How else would you describe a project to re-create note for note one of the most famous jazz albums of all time? That famous album, of course, would be Kind of Blue.

Some other people may say it’s “unnecessary.” “Interesting.” “Foolish.” “Impudent.” “Inscrutable.” “Sardonic.” “Outrageous.” “Unoriginal.” “Blasphemous.” Or “mischievous.”

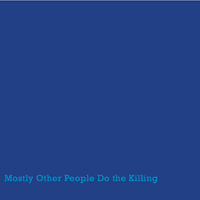

Mostly Other People Do the Killing’s new album, Blue, indeed shows due respect for the original. MOPDtK doesn’t re-interpret Kind of Blue. It doesn’t use Kind of Blue as the basis for another project inspired by it. Instead, the band, known for its breaking of rules and for its originality, breaks rules once again by being unoriginal.

One can imagine the time and effort involved in notating Kind of Blue, not to mention listening to the album maybe hundreds of times to capture the tone and spirit of the album’s performances. Ron Stabinsky had to understand and play with the techniques of Bill Evans and Wynton Kelly. Band leader Moppa (Matthew) Elliott had to re-create Paul Chambers’s note placements, rhythms and resonances. Peter Evans, muted occasionally now and more subdued than usual, had the cheekiness to imitate Miles Davis. And then there was Jon Irabagon studying and imitating jazz icons Cannonball Adderley and John Coltrane—for sure, a seemingly impossible feat to possess sufficient versatility to suggest Adderley’s irrepressible joyousness and Coltrane’s infinite depths of spirituality, not to mention their distinctive tones. Drummer Kevin Shea had the honor of slipping into Jimmy Cobb’s musical frame of mind in 1959.

What would Jimmy Cobb, the only surviving member of Kind of Blue, think of this?

One wouldn’t know from the liner notes.

Once again provocative, unexpected and droll, MOPDtK, and probably namely Elliott, publishes in the liner notes a 1939 (very) short story by Jorge Luis Borges entitled “Pierre Menard, Author of the Quixote.” At first a puzzling avoidance of jazz description, which of course is what jazz listeners have come to expect from liner notes, Borges’s story becomes relevant, and revelatory, to Blue. Its plot describes a “translator” of Don Quixote who becomes so immersed in his work that he rewrites it word for word in its original Spanish. The hilarious, and sarcastic, part of the story occurs when Borges “compares” exactly the same words from the original Cervantes novel to Menard’s copy, but with different interpretations for each, due to the knowledge in hindsight that two writers, one Spanish and one French, published each one.

A word-for-word “interpretation.” And then, a note-for-note “interpretation.” Sly, MOPDtK is.

Even Bill Evans let listeners in on his thoughts about Kind of Blue when he compared in its notes a spontaneous Japanese painting technique to group musical improvisation. In those notes, Evans let us know that Miles Davis had sketched the ideas for Kind of Blue only hours before the recording, allowing “something close to pure improvisation.”

Not so with Blue. It’s not improvisation at all. And because of this, is it jazz? Is it art? Is it worthy of recording at all?

As it turns out, these are exactly the questions that MOPDtK wants listeners to ask. By choosing one of jazz’s best-known albums for re-recording without deviation by a new generation of musicians, the band provokes listeners to compare the two albums.

And that’s the point.

Elliott acknowledges that it’s impossible for the musicians of Kind of Blue and Blue to sound the same because separate musicians recorded each album. As a result, Blue’s provocation encourages close listening to both albums to notice the differences. And of course, there are many. In an interview with his brother, Greg Elliott, Moppa asks, “Why [don’t people] listen to all music like that? Hopefully, this will wake people up.”

In other words, Blue becomes an in-your-face original project unto itself by promoting critical appreciation—a skill that Elliott believes has diminished or disappeared among some listeners.

In addition, Moppa Elliott takes a shot at the techniques of jazz education, as well as the establishmentarianism of jazz, by suggesting through Blue that note-for-note performances of transcribed solos doesn’t help students learn to search their own souls to improvise or to develop their own styles. It helps them perform other people’s music, as does, according to Elliott, classical music, which also involves note-for-note performances. Tone, personal articulation, style and other spontaneous values are what’s important in jazz, according to Elliott.

The Blue project started as a notion when Elliott and Evans “what-if-ed” the idea when they were students in 2002. After going ahead with a single transcription, the project eventually grew into Blue. Even though MOPDtK’s previous albums investigated the styles of other legendary jazz musicians, the Blue quintet became the Kind of Blue sextet with an imagined absorption of spirit. Even though previous MOPDtK album covers parodied famous artwork like Keith Jarrett’s The Köln Concerts’s, Blue’s doesn’t. Surprisingly, it’s totally blue. Imagine that. Not a splash of any other color to be seen. Not a single graphic reference to Kind of Blue’s famous album cover.

So, as Lloyd Bentsen would have noted, Peter Evans is no Miles Davis. Jon Irabagon is no John Coltrane. Nor Cannonball Adderley. On the other hand, Miles Davis was no Peter Evans, and John Coltrane and Cannonball Adderley were no Jon Irabagon. Et cetera. That goes without saying, even though it was said.

The point being that musical expression arises from the artist’s personality and technique. E.G., Coltrane’s solo on “Blue in Green” continues to affect me after perhaps hundreds of listens. Its descending intervals, its soulful tone, its contrast of long tones with that quick phrase, its final evaporation. Irabagon plays the same notes with similar technique, but his tone is different.

See? I listened and compared. That’s what Elliott wanted to happen, and I fell into his snare, just as will others who listen for differences. Evans similarly plays the same notes as Davis, and with comparable pauses and a similar muted sound. But does Evans capture Davis’s soulfulness or his melancholy style? The listener can judge.

Still, MOPDtK deserves credit for staying true to its quintet assemblage, even though Davis’s KOB group was a sextet. That means that Iragabon had to play both alto and tenor saxophones and to absorb Adderley’s and Coltrane’s techniques and personalities. This double duty presents Irabagon with an admirable challenge when he plays in harmony the saxophones’ vamp for “All Blues,” even though its accomplishment doesn’t beg for comparison in the ways that solos do. For instance, Evans plays “All Blues,” yes, muted and then with an open bell, and with all the smears and momentary swing and dynamics as well. But still, of course the solo isn’t improvised (though few could tell the difference from this and the original), and his tone varies, but slightly. Admirable imitation, these tracks are.

So diligently did MOPDtK analyze Kind of Blue that Blue’s length is the same as KOB’s: 45 minutes and 44 seconds. Amazing.

But is it real or is it Memorex? Is it art or is it imitation?

Blue is MOPDtK’s musical intellectual trigger. By rigorously imitating down to its finest ineffable details jazz’s best-selling album, and one of its most revered, MOPDtK begs comparison. And then it lures listeners into the close listening experience that every quality recording deserves, not matter what the genre.

The Miles Davis Sextet did the killing with Kind of Blue’s memorable improvisation. Mostly, MOPDtK does too with its subversive controversial idea respectfully executed.

2014

Label’s site: www.hotcuprecords.com