Artists eventually do go home again, if not physically, at least in spirit, as they realize that their upbringings formed the bases of their artistries, even as their talents may have been transformed years later. Innumerable musicians and singers recall their early discoveries of music in the church, in hometowns like New Orleans or Detroit, in schools, or in other countries before moving to the U.S. That happens to be true of Matt Wilson too, who has always incorporated references to his Midwestern country background into his music from his first album, As Wave Follows Wave. Even at the start, Wilson wanted to make sure that he recorded reminiscences of scurrying chickens and the delights of bingos! and the comforting sensations of farms and the final warnings of auctions and high-school football cheers and the creaking of an Old Porch Swing. Even after moving to New York City and building his Big Happy Family of musicians there, Wilson has proven that you can take the drummer out of the Midwest, but you can’t take the Midwest out of the drummer.

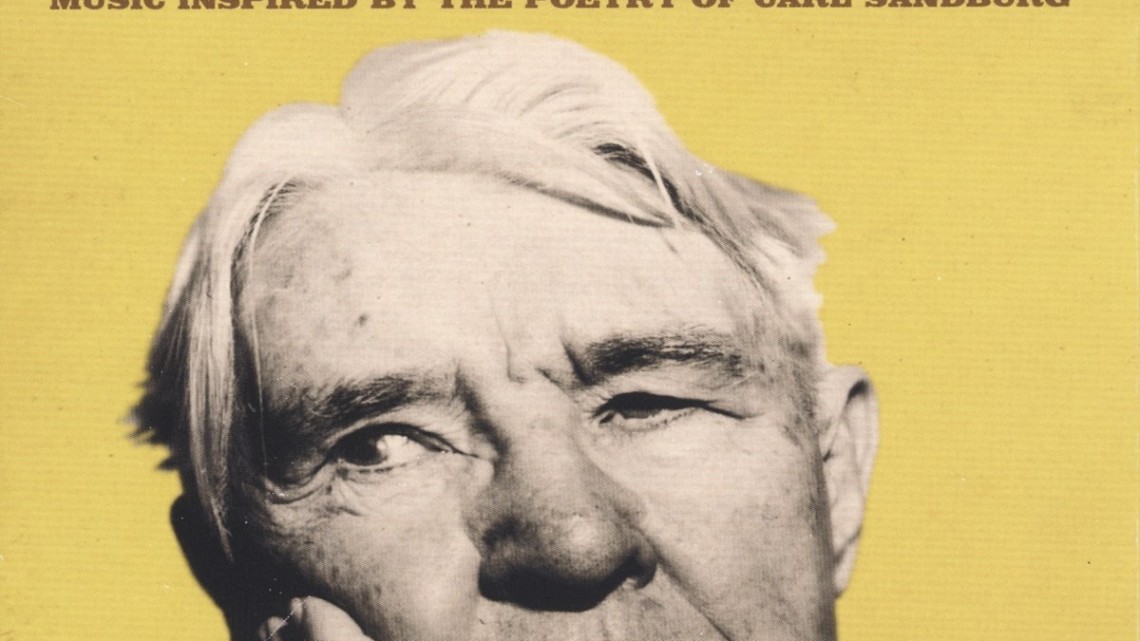

As Wave Follows Wave was a foreshadowing of Wilson’s recordings to follow, not only because of its declaration of his musical roots in his hometown, but also because of his understanding of the cadence of poetry in music. Despite Wilson’s penchant for uplifting the spirit of any performer he accompanies, his own recordings have been remarkably consistent as they have incorporated the music of poetry into the poetry of music. Slyly, Wilson recognizes the rhythm of a porch swing as its familiarity evolves into music, and he hears the extremes of tension and release in the drama of an auction. Sharing a similar background was poet Carl Sandburg, whose hometown was one town over from Wilson’s in Illinois. In fact, the title of Wilson’s first album was also the title of a Sandburg poem, included in From the People Yes, which attained greater meaning for Wilson as the years progressed. Now, Wilson had dedicated to the poetry of Sandburg an entire album, which is yet another attestations to his authenticity and originality.

As it turns out, Wilson is the most recent in a tradition of jazz artists who have been inspired by or who have inspired poets, these poets likewise recognizing the affinities between jazz and poetry. There were the beat poets who interacted with jazz musicians, such as Dexter Gordon/John Clellon Holmes or Stan Getz/Lawrence Ferlinghetti. And there were also Wynton Marsalis/Maya Angelou, Charles Mingus/Langston Hughes, Kurt Elling/Kenneth Rexroth, Max Roach/Oscar Brown, Tyrone Brown/John A. Williams, Cleo Laine/William Shakespeare, Luciana Souza/Pablo Neruda, Tim Berne/Tracy K. Smith, Phil Woods/A.A. Milne, Maria Schneider/Ted Kooser, Oliver Lake/Huang Xiang, Fred Hersch/Walt Whitman, Bob Kindred/Josef Mohr, Jane Ira Bloom/Emily Dickinson, Henry Threadgill/Derek Walcott, Billie Holiday/Abel Meeropol, Laurence Hobgood/Robert Pinsky, Jayne Cortez/Denardo Coleman, Lisa Sokolov/Stanley Kunitz, Booker Ervin/Kenneth Patchen, Jay Leonhart/Robert Frost, Gary Bartz/Daisaku Ikeda, David Amram/Bob Kaufman, Vijay Iyer/Mike Ladd, Art Blakey/Michael L. Newell, Noah Haidu/Rainer Maria Rilke, Steve Swallow/Robert Creeley, Don Byron/Sadiq Bey, Mark Murphy/Jack Kerouac, Carla Bley/Paul Haines, John Tchicai /Yusef Komunyakaa, Pete Malinverni/Psalms, Kate McGarry/e e cummings, Bill Frisell/Allen Ginsberg, Arturo O’Farrill/Christopher “Chilo” Cajigas, David Murray/Aleksandr Pushkin and Patricia Barber/Ovid. The beat goes on. In each case, poetry, enhanced by music, provided within their souls deeper definitions of who they are/were.

Wilson too. He admits that he found solace in the Illinois-derived poetry of Carl Sandburg. And now Wilson has assembled another family of musicians and unlikely poetry readers who not only participate in Wilson’s celebration of Sandburg, but also reveal previously unheard aspects of their own personalities as they give voice, in spoken instead of melodic cadence, to Sandburg’s poems. As the creative force behind Honey and Salt and the leader of the poetry jamming, Wilson chose the poems of greatest appeal to him and recruited a diverse group of participants in the appreciation of Sandburg, who, Wilson believes, is due for reappraisal by another generation. Moreover, all of the artists involved in the project understand the underlying humor and the plain-spoken Sandburgian descriptions, the poet’s humility and lifelong connection to Illinois roots exemplified by the album’s title that recalls everyday objects.

And we hear well-known musicians’ revealing personality traits that were previously unheard, but are finally recorded, as if such unexpressed concerns connected with the appropriate opportunities provided by Sandburg’s poetry. For instance, we hear Joe Lovano reading “Paper 1,” briefly to be sure in but 44 seconds, but still Lovano has time to engage the listener with the question, “Are you a reader or a wrapper?” [The explanation of the terms are explained within the poem.] We hear Rufus Reid’s dramatic reading of “Trafficker,” which is an unusually dark Sandburg poem and which includes a nourish description of a street walker with “her beauty wasted, body faded, claims gone, and no takers.” Or, surprisingly, we hear a more practiced orator of sorts, actor Jack Black—the husband of Tanya, daughter of Charlie Haden, who was another jazz musician who celebrated his Midwestern country upbringing. Black reads Sandburg’s appreciation of jazz, “Snatch of Sliphorn Jazz,” written during the twentieth century when poets like T.S. Eliot and Robert Pinsky were experimenting with the then-unusual cadences of jazz.

As for the readers (mentioned above) who already collaborated with poets, we hear Bill Frisell’s soft-spoken reading of “Paper 2,” the bookend to Lovano’s “Paper 1.” The longer “2” allows for Jeff Lederer’s full-throated tenor sax outpouring and Dawn Thomson’s guitar groove. And we hear Carla Bley read “To Know Silence Perfectly” [“is to know music”], which uses to dramatic effect: silence. Silence that separates the improvisations.

In addition to the guests, who graciously accepted Wilson’s invitations for participation, we hear Wilson himself reciting “As Wave Follows Wave,” yet again twenty-one years later and still on Palmetto Records. The relevance of Sandburg’s poem became more evident during the intervening years as its wisdom describes everyone’s eventual experiences. Still, the poem read by Wilson (“Men live like birds together in the wood”) reflects to a degree the sentiment of the one read by Black (“Be happy, kid, go for it, but not too doggone happy” [emphasis mine]): that is, the pursuit of joy in conjunction with the fear of its loss cautioned by wisdom. And we hear the bard, Sandburg himself, reciting his famous “Fog” poem accompanied decades hence by his admirer as Wilson provides his own supplemental cadences and responses while his percussive voice recites the poetry of the drums. No doubt Sandburg, who enjoyed writing comical verses about improbable situations, would relish the adaptation of his poetry to rhythm and pitch, a merging of the arts and crafts of literature and music. Wilson’s talent and knowledge of Sandburg’s works allow for like-minded humor, which has consistently infused Wilson’s recordings, in heightening the effect of the poems with music.

Even without the collaboration with well-known readers, Wilson’s group captures the appeal of Sandburg’s occasional poetry of absurdity with its own musical wittiness and professionalism. The opening track, “Soup,” combines satirical poetic observation (“I saw a famous man eating soup” [how ordinary and perceptive he was in capturing everyday absurdities]) with a “Green Onions”-like groove, but slower. Thomson sings with all seriousness the incongruous lines about soup-slurping that no one would expect to match the quintet’s swing. Wilson matches droll Midwesternism with Midwestern stroll. Yet, Thomson is such an accomplished singer, in addition to her guitar chops, that she can sing “I Sang” with free-hearted, free-throated countryside sincerity through sustained notes/words describing the eternal theme of unrequited love. Compensatingly, reedman Jeff Lederer, who contributes the clarinet solo to “I Sang,” reads Sandburg’s words from “Prairie Barn” (“…the barn was a witness, stood and saw it all”) over Thomson’s acoustic guitar accompaniment of major chords and contemplative poignancy. Thomson recalls Sandburg’s affinity for self-accompaniment while singing his own folk songs.

Obviously deeply understanding the history and meaning of Sandburg’s poems, Wilson has organized Honey and Salt into four categories that progress from Sandburg’s country life in Galesburg, Illinois to his immersion in the energy of the cities, specifically Chicago, to his synthesis of the two geographical influences, and finally to his time spent with family in North Carolina. An album considered for decades, Honey and Salt now allows Matt Wilson to devote his own talent, energy and imagination to the recording of Carl Sandburg’s poems for a new generation to hear with fresh appreciation.

Artist’s site: www.mattwilsonjazz.com

Label’s site: www.palmetto-records.com