Except for occasional flare-ups of its La Soufriere volcano, the hilly eastern Caribbean island of St Vincent tends to keep a low profile among the least developed but politically stable nation states of the region.

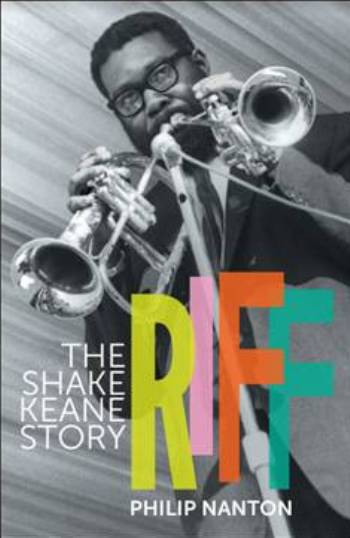

Philip Nanton’s pioneering biography, Riff: The Shake Keane Story, chronicles the outstanding but turbulent life of a man whose unique creativity transcended the limiting confines of the island of his birth.

Nanton, a poet, writer and former academic at the University of Birmingham and the University of the West Indies, draws on three main themes - Vincentian and broader Caribbean nationalism, migration and masculinity – to flesh out the life of one of the Caribbean’s foremost jazz trumpeters and poets.

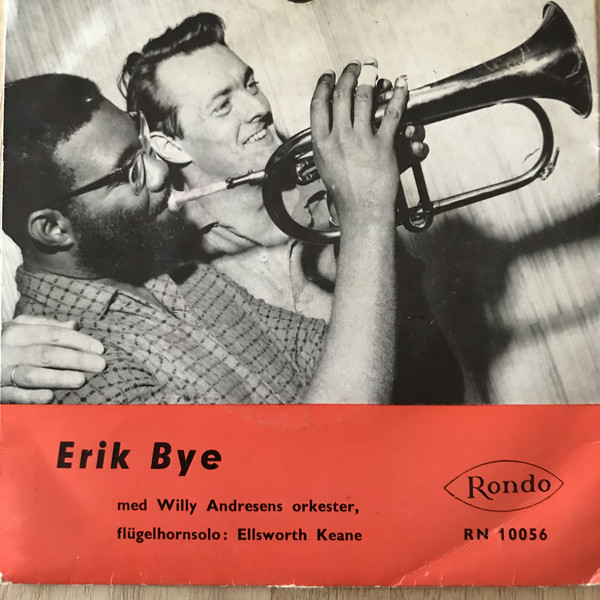

Ellsworth McGranahan Keane was born in Kingstown, St Vincent, on 30th May 1927 into a family possessed with a love for music and education. Mentored by his strict trumpet-playing father Charles, the young boy displayed an early talent for music, giving his first recital at the age of six.

Alongside his love of music was a prodigious yen for languages and literature, leading to him being dubbed ‘Shakespeare’ by school friends, subsequently shortened to ‘Shake’.

The slenderness of Riff: The Shake Keane Story (157 pages) belies its weighty and sometimes troubling insights into Keane’s contrasting expressions of black masculinity.

Nanton astutely traces his evolution from a child growing up in the early 20th Century post-slavery West Indian milieu of his day, to a budding and published poet-musician. We learn about Keane the freelance African-Caribbean BBC broadcaster and University of London student who fails to complete his studies. We glean an understanding of Keane the estranged husband and absent father. The reader also gets a firm grasp of an intellectual whose exploits in cultural leadership and local politics come to an abrupt end on his return to St Vincent after two decades in England.

Indeed, Nanton’s portrayal of Keane reveals an artist whose life is characterised by serially thwarted ambitions and misfortunes. Jazz connoisseurs will doubtless appreciate the meticulous detail with which the author has explored Shake Keane’s jazz and poetic nous.

Already an established poet when he arrived in London in 1952, the larger than life Keane authored L’Oubli, his first self-published collection of poems in 1950. This was followed by Ixion (1952), One a Week With Water and The Volcano Suite (1979) and Palm and Octopus (1994).

Nanton’s chapters and appendices provide ample examples of Keane’s poetry, shining a bright light on his adept deployment of jazz meters, puckish wit and acute social observations, often counterbalanced by a wistful quality.

Keane’s questing and arresting trumpet sound stood out in Jamaican-born alto saxophonist Joe Harriott’s path-breaking free form jazz bands of the 1960s, featuring another Jamaican musician and close friend, Coleridge Goode, who played double bass.

The group’s notable albums, Free Form (1960), Abstract (1963) and Movement (1964) are considered classics in their genre.

Keane was also a constituent element in the groups of pianist Mike Garrick, marrying jazz with poetry and choral singing. However, Nanton points out that the Vincentian trumpeter/poet maintained separate jazz and poetry personas, shying away from performing his own poetry with Garrick. His exciting trumpet and flugelhorn sound was also found in calypso and West African high-life bands in the 1950s and 60s.

In 1965, Keane left Britain for more lucrative work with the Berlin-based Kurt Edelhagen Orchestra – one of the leading German jazz orchestras of its day. He also performed with the Kenny Clarke/Francy Boland Big Band.

In 1972, Shake took up the invitation extended to him by St Vincent Premier, James ‘Son’ Mitchell, to be the country’s first Director of Culture.

As Nanton carefully illustrates, those close to Keane counselled him not to get involved in the island’s pre-independence politics but he stubbornly refused their advice. It turned out to be a disastrous episode: Mitchell lost the country’s general election in 1974. His successor, Milton Cato, had no interest in the cultural leadership Keane was offering to Vincentians.

Between 1975 and 1981, Keane remained in St Vincent, teaching at secondary schools and crafting well-wrought verse. His collection of poems, One a Week With Water, won the prestigious Casa de Las Americas regional prize for poetry in 1979.

The restless Keane relocated to Brooklyn New York in 1981, living between the USA and latterly in Norway – where he began to get stable musical and television work in in the 1990s.

He headlined the Barbados Jazz Festival in 1989 and performed with Linton Kwesi Johnson and Dennis Bovell on Real Keane: Reggae into Jazz (1991).

Shake Keane died of stomach cancer in Oslo in 1997 at the age of 70.

With attractive black and white photographs which greatly assist in telling the story, together with fragments of Keane’s poetry at the start of each chapter, Nanton admirably succeeds in writing a highly engaging account of one of the Caribbean’s legendary creative forces.

Riff: The Shake Keane Story, by Philip Nanton (Papillote Press, 157pp)