Zev Feldman has built upon rewarding opportunities throughout his career to become, within 15 years, the go-to archival jazz producer. Admiration for Feldman grows not only for uncovering high-value recordings thought to be nonexistent—until, thanks to his efforts, they weren’t. Also, Feldman strives for uncompromising quality to achieve advanced sound restoration. Furthermore, he delights jazz enthusiasts with spruced-up marketing techniques.

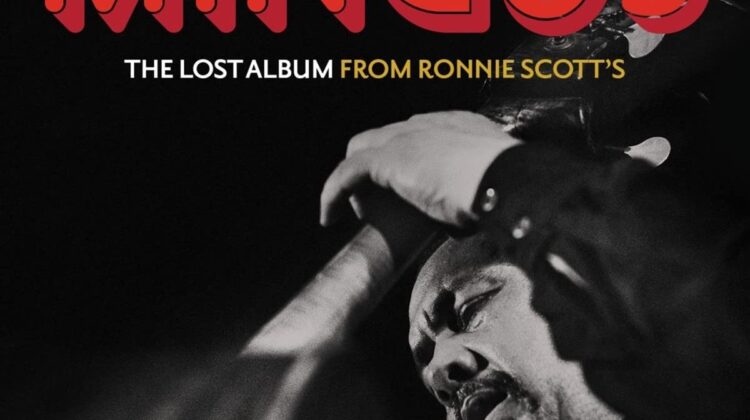

Recognizing Feldman’s energetic potential, George Klabin of Resonance Records seeded one of Feldman’s embryonic projects when Feldman unearthed a jazz master’s forgotten jazz recording.

That germination thrived as it developed into several branches. They included the establishment of new jazz labels such as the Jazz Detective label, accurately named. In addition, Feldman has collaborated on the production of releases by renowned labels such as Blue Note and Elemental. And his work with Klabin continues to flourish.

In a relatively brief span of time, Feldman has been responsible for an impressive collection of respected first-time releases of archival recordings. One lead has led to another. More and more frequently, Feldman has gleaned tapes that sound engineers and jazz enthusiasts had lain dormant in their closets, trunks, basements, and workrooms for decades.

These prescient witnesses to significant events in jazz history plugged in their reel-to-reel tape recorders, set up their microphones, and pushed the Start buttons. Although they may have sensed that they were logging something important, they apparently didn’t have the resources or the contacts to market the marvelous performances happening in front of them.

Along came Feldman. Now they do.

Feldman’s worldwide reputation has broken through thorny geographical barriers to plum the depths of jazz recordings that had been squirreled away in places as far apart as Hilversum, Holland and Seattle; Buenos Aires and Las Vegas; Paris and Baltimore; London and New York.

As the result of the outgrowth of Feldman’s enterprise, jazz record collectors now can celebrate the launch of Time Traveler Recordings label, which consists solely of limited-release vinyl records mastered from the original tapes.

How substantially?

Well, Feldman has negotiated the rights to reissue evergreen jazz albums from the prolific Muse label, whose releases in the 1970’s documented the extraordinary talents of prominent jazz artists.

Going back to the future, Muse meets Time Traveler.

This mutual collaboration is significant—for the pure enjoyment of collectors who pined for the availability of classic Muse albums.

Ever the connoisseur who knows the importance of preserving for the future the albums that he re-releases, Feldman decided to enclose the records in gleaming jackets that augment the impression of the albums’ original cover designs. In addition, Feldman recruited present-day jazz writers to provide essays for the backs of the jackets.

After careful deliberation, Feldman decided to introduce the recordings of three jazz musicians whose albums from the seventies, rare until now, had been commanding high prices among collectors.

The chosen musicians are Kenny Barron, Roy Brooks, and Carlos Garnett.

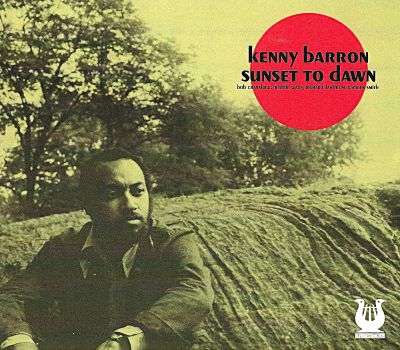

Kenny Barron’s reputation had been growing because of the poplarity of his recorded accompaniments with legendary jazz musicians. The founder of Muse Records, Joe Fields, recognized that Barron’s imaginative early collaborative work suggested that he wood offer a unique musical identity that could flourish if he established his own group. As a result, Barron’s 1973 Muse album, Sunset to Dawn, was his first as a leader as he em-barked upon creating a legendary oeuvre.

Performing with bassist Bob Cranshaw, vibraphonist Warren Smith, drummer Freddie Waits, and percussionist Richard Landrum, Barron seized upon the opportunity to create a concept album whose tracks, all but one written by Barron, range, appropriately, from “Sunset” to “Dawn.” Consistent with the sounds of the times, “Sunset” opens with the electric piano’s otherworldly shimmering tones, a la 2001: A Space Odyssey, until Cranshaw’s vamp at 2:13. Then, at 2:53, after the sun has set, Barron introduces the theme, reminding the listener of the lyricism and beauty of Barron’s style, already present early in his career when he finally broke free from his role as an accompanist. The final track, “Dawn” as the rosy awakening, bookends, naturally, “Sunset,” with Barron’s impressionism and modality as leaves glisten and as the dawn brightens and gathers vitality that’s topped out by Waits’s energy and Landrum’s palmed patterns on congas.

In between descriptions of a day’s extremities, Barron switches to acoustic piano on “Al-Kifha” and “A Flower,” and “Delores Street, S.F. (recorded again on Barron’s The Only One and Spiral albums). Even at the beginning of the album, Barron switches to double time with the rapidity of 64th-note improvisational phrases that continue to this day. Waits’s “Al-Kifha” showcases the cohesion and vitality of the group, Barron’s quick improvisation peared with Crawshaw’s lunging electric bass lines and Waits’s fervent dynamism.

The success of Muse Records resulted from Fields’s respect for the individuality of the jazz musicians. Unlike other labels such as many of those in the CTI 3000 Series, an overriding style did knot characterize Muse’s releases. The multitude of styles rooted in the jazz tradition contributed to the variety inherent in the label’s records.

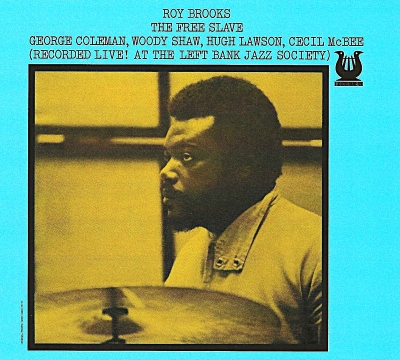

Roy Brooks had something to say, and he was free to say it on Muse. Brooks’s ringing Black activism statement, documented in The Free Slave album, provides a distinct contrast to the naturalistic theme of Barron’s album.

Another difference between the two albums involves their recording environments. In 1973, Barron recorded Sunset to Dawn, produced by Don Schlitten, in one of five studios in RCA’s New York facility, which was equipped with nine tape mastering rooms and five mastering channels.

Brooks performed The Free Slave in a recording atmosphere that contained less control from commercial engineers and more expressive freedom from a community of individuals who were passionately inspired. Those individuals comprised a live audience in Baltimore’s Famous Ballroom, whose famous concerts, managed by The Left Bank Jazz Society, have become available on various labels throughout the ensuing decades. In fact, Muse didn’t release this 1970 recording of Brooks’s quintet until 1972 as its third album.

Fortunately, sagacious recording engineer Orville O’Brien documented on reel-to-reel tapes the Famous Ballroom concerts—informal Sunday-afternoon neighborhood events fir which the audience members brought their own drinks, fruits, vegetables, and home-made meals, which they shared with each other…and with the musicians. Extraordinary interactions occurred between the members of Brooks’s quintet and the audience, their musical conversations possibly lichened to a concert-length call-and-response session. O’Brien recording captures the audience’s reactions to this remarkable event.

Knowing his audience, Brooks started the concert with the piece that establishes his theme, “The Free Slave.” Driven by pianist Hugh Lawson’s repetitive augmented minor third chords, Cecil McBee’s trance-like vamp, Woody Shaw’s doits and falls, and Brooks’s burly propulsive force, the group wordlessly, but with an irresistible groove, immediately attracted the soul of the audience to his “worship service.” When saxophonist George Coleman entered, this exciting lineup was complete. Brooks wrote all but one of the albums compositions, McBee’s “Will Pan’s Walk” being the exception.

Brooks’s life story after the seventies was one of continuing tragedy. Despite his work with jazz legends like Horace Silver, Chet Baker, Sonny Stitt, and Yusef Lateef, Brooks recorded inconsistently. A true original, though, he explored non-conventional musical methods, such as vacuum-tube drumming, musical saws, and the limber use of non-Western percussive instruments.

The paucity of Brooks-led recordings diametrically increased interest in his rare talent…and in the value of his albums. So, wouldn’t you know it? Feldman was instrumental in working with Cory Weeds to release on the Reel-to-Real label another Roy Brooks quintet album that was recorded live at the Famous Ballroom: Understanding.

Coincidentally, “Understanding” is the second track on The Free Slave, and it proceeds at a more calming pace than “The Free Slave’s,” offering Coleman and Shaw expanded solos of expressive intensity and contrasting dynamics. “Five for Max” commences with the audience’s enthusiastic demand for another tune. A lyrical tribute to his mentor, Max Roach, the piece features Brooks’s solo that includes his changing of the drums’ pitches by using the vacuum tubes.

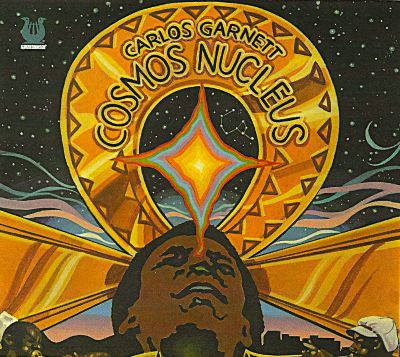

As if to demonstrate the contrasts of styles that Muse Records embraced, Feldman chose as Time Traveler Recording’s third release Carlos Garnett’s 1976 Cosmos Nucleus album. Another Muse recording artist who deserves belated attention, Garnett (who played saxophone on Understanding) assembled not only a core septet, but also an 18-piece horn section—and a vocalist. After working with Freddie Hubbard, Art Blakey, and Charles Mingus, Garnett, a Panamanian native, recorded on his own. His first big-band album (“big” = 25 parts), Cosmos Nucleus encompasses all his childhood musical influences from the music he heard as ships passed through the Canal.

For instance, on “Wise Old Men,” Garnett sings his own lyrics over his samba arrangement, percussiveness being a constant in all of the tracks. Singer Cheryl P. Alexander shapes his lyrics for “Mystery of Ages,” which asks Garnett’s metaphysical question: “What am I here for?” The chorus’s answer sticks: “Nobody knows.”

Rather than using the brass for accents or fills, Garnett arranged the horns’ parts to create towering orchestral textures, as on the band’s backup to his solo on “Kafira.” Garnett’s extended arrangements, such as the one on the 12-minute track, “Cosmos Nucleus,” include separate sections and moods, as if it had been written as a suite. His generosity cultivating vibrant musical engagement, Garnett provided opportunities for young musicians starting their jazz careers, such as Wayne Cobham, Billy Cobham’s brother; Cecil McBee, Jr., the son of the bassist; and 18-year-old Kenny Kirkland.

Feldman states that the common element for Time Traveler’s future quarterly releases will stem from his interest in all Muse artists, including blues musicians, who deserve more attention in the twenty-first century.

And so, we celebrate the budding start of Time Traveler Recordings.

Mr. Feldman: Take a bough.