Zev Feldman, who goes by the sobriquet of the Jazz Detective, has moved on to apply his investigatory expertise, in a category of its own, to a new label.

That label is named, appropriately enough, Jazz Detective.

Jazz Detective is a division of yet another new music entity of Feldman’s, Deep Digs Music Group. That group releases archival recordings of musical genres in addition to jazz.

Both enterprises—divisions of yet another, larger Barcelona-based company, Elemental Music Records—strive to bring to light (or rather, to bring to sound) important recorded performances, forgotten or previously unavailable, that complement jazz icons’ revered famous recordings.

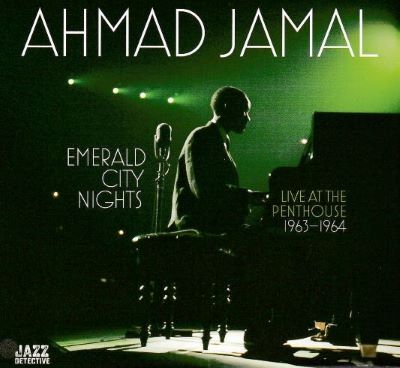

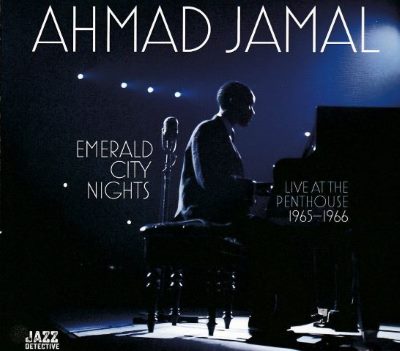

No doubt about it, the combined releases of Ahmad Jamal’s Emerald City Nights recordings are culminations of Feldman’s discovery of tapes recorded at the Penthouse in Seattle’s Pioneer Square.

To date.

Feldman leveraged his earlier work with the Penthouse’s prescient owner’s son, Charlie Puzzo, Jr., who archived the performances’ tapes; and with recording engineer Jim Wilke, who was the announcer of a weekly live jazz broadcast in the late sixties from the Penthouse on radio station KING-FM. Together, they collaborated to produce Resonance Records’s Live at the Penthouse by The Three Sounds with Gene Harris and Smokin’ in Seattle: Live at the Penthouse with Wes Montgomery and Wynton Kelly.

As is Feldman’s wont, his first Jazz Detective project proves that the new label’s releases will not skimp on quality, either recorded or written or packaged.

The Emerald City Nights: Live at the Penthouse events started with the release of two limited-edition (of only 3,000 units) double volumes in vinyl format on 180-gram discs that typically sell out in stores. Then Jazz Detective released both albums in streaming and CD formats.

The colorful and informatively detailed CD packages include concert photographs and posters; introductory essays by Feldman and Eugene Holley, Jr.; interviews with Wilke, Puzzo, Jr., and Marshall Chess, whose father, Leonard Chess, co-founded Chess Records, on which Jamal first recorded; and interviews of appreciation for Jamal with jazz pianists Ramsey Lewis, Kenny Barron, Jon Batiste, Aaron Diehl, and Hiromi Euhara.

The capper is Feldman’s interview with Ahmad Jamal, the artist himself, who at the age of 92 gave enthusiastic approval for the project.

Unlike the circumstances surrounding most of Feldman’s previous projects, Jamal was available to provide background information about the recordings, approve the packages’ photographs, suggest musicians for the interviews, and help supervise the production of the recordings.

As always, eschewing the work of counterfeiters out of respect for the musicians, Feldman firmly adhered to strict ethical standards by being above board, paying for the rights, paying the lead musicians and the sidemen, and keeping track of royalties.

The results are, at least so far, two of Jamal’s most important releases, which offer significant discoveries for listeners unfamiliar with his style.

Unfortunately, a 1958 DownBeat review described Jamal’s style as “cocktail music.” Jazz journalists repeated that dismissive term throughout the decades without investing time in active listening. Or without appreciating the musical values of the hugely popular recording of “Poinciana,” as did not the DownBeat reviewer, who described it as “emotionally, melodically, and organizationally innocuous.”

Similarly, the public may remember Jon Batiste, lionized now as was Jamal in the 1950’s, more for “We Are” or as the band leader on The Late Show with Stephen Colbert, despite his wide-ranging, individualistic talent. Doc Severinsen too may be overlooked as a trumpet virtuoso, even though jazz writers sometimes relegate him to being an entertainer for leading The Tonight Show band, his singular choice of clothing, and his antics with Johnny Carson. But saxophonist Ernie Watts, formerly a Tonight Show band member, said, “When you hear someone like [Severinsen], you know what ‘great’ is.”

Listen to more than “Poinciana.” Listen to rest of Jamal’s music. Listen to his technique. Listen to his originality. Listen to his mastery of the piano. Listen to his musical surprises. Listen to his narratives. Listen to his joy. Listen to his wordless humor. Listen to his silences.

The Emerald City Nights: Live at the Penthouse releases provide abundant opportunities to do so.

The musicians know.

Miles Davis was one of earliest jazz musicians to be entranced by Jamal’s technique as Davis arranged some pieces with nods to Jamal’s musical approach. Reportedly, he encouraged Red Garland to adopt some of Jamal’s technical elements.

Saxophonist Ted Nash said, “The way [Jamal] comped wasn’t the generic way that lots of pianists play with chords in the middle of the keyboard, just filling things up. He gave lots of single line responses. He’d come back and throw things out at you, directly from what you played. That’s something I don’t feel with a lot of piano players.”

And of course the jazz pianists’ appreciations in the albums’ booklets leave no doubt about their respect for Jamal’s influence. For example, Kenny Barron writes: “So he leaves all of this space for the rhythm section…to finish an idea…. It’s like he orchestrates from the piano…. And of course, his technique is flawless.”

Even unto the age of 88, when Jamal released his most recent solo album, Ballades.

Already popular because of his best-selling album, At the Pershing: But Not for Me, which included “Poinciana” in its track list, Jamal arrived at the Penthouse with a large following and with his established style already intact. Influenced initially by Erroll Garner, Nat Cole and Art Tatum, Jamal synthesized their influences and personalized what he was hearing. He established his own orchestral approach consisting of entrancing percussiveness, moments of silence when audiences could still hear the rhythm and be surprised upon Jamal’s heavily accented re-entries, dabs of sonic humor, broad sweeps across the entire breadth of the piano, spontaneous interactive exchanges with his bassists and drummers, and an expressive touch.

The singularity of his playing didn’t pander to night club audiences, who after all paid to be entertained, even as his brilliance aroused appreciative applause and delight.

As if in defiance of “Poinciana” stereotypes, Jamal opens Emerald City Nights: Live at the Penthouse with his own percussive six-eight vamp (eighth-note/eighth-note/sixteenth-sixteenth [da da da-da] repeated thrice and then rest/eighth/eighth) before his upswept water spouted glissando introducing the fast-paced melody. The bridge of “Johnny One Note,” the first track, is even faster at double time in four-four because the return to the meter of three. And then bassist Richard Evans and drummer Chuck Lampkin pick up the rumbling rhythm as Jamal abandons bar lines and extends forceful thick chords over several measures or in repeated triplets, fragments of melody occurring here and there. The introductory number for the June 20, 1963 performance nears its conclusion with a stirring solo by Lampkin. Then Evans’s solo emphasizes the meter of three over which Jamal tosses in riffs whose harmonic roots change with each repetition.

And so it goes throughout the concert, “Johnny One Note” being a representation of all that will ensue. More excitement and more surprises follow.

One of those surprises is Jamal’s flowing allegro Bach-inspired counterpoint on Evans’s “Minor Adjustments” before the improvisation in four over the, yes, G-minor chords. The Garner influence is evident as Jamal’s prodding chords in the left hard push the irresistible rhythm (at one and three) with intimations of swing as gales and showers of notes swirl without pause in the upper register. Dramatically, the piece ends with the repeated counterpoint and then rippling rhythmless cadenzas and treble-clef tremolos over Evans’s arco accompaniment.

“All of You” proceeds along with a relaxed hard-four stroll, an inviting foundation for Jamal’s leisurely improvisation. His performance nonetheless creates moments of humor with bits of quotes like “Do Nothing ‘Til You Hear From Me,” quivering tremolos, multiple turnarounds, broad chords anticipating the beat, and moments of tension and release with quick signature scampers to the top of the keyboard and back, suggesting that if the piano had more than 88 keys, Jamal would have played those too.

Jamal’s trio closed out the 1963 concert with Johnny Hodges’s “Squatty Roo,” a fast-paced crowd pleaser which provides opportunities to feature Evans and Lampkin as they trade fours with Jamal until he takes the lead at 2:57. his left hand’s chords pulsate while he develops upper-treble-clef turbulence and sweeps, as well as dramatic contrasts of volume (not to mention a droll “Fascinatin’ Rhythm” quote).

Puzzo looked forward to Jamal’s concerts at the Penthouse to the extent that he switched from a smaller grand piano to a concert grand piano during his engagements. Packing the house in 1963, Jamal returned to the Penthouse the next year, bassist Jamil Nasser substituting for Richard Evans. Fortunately, Wilke recorded those concerts too, and they are now available in the same double-CD package.

Despite the absence of Evans, his minor-key composition, “Bogota,” commences the March 26, 1964 concert. Similar to Cedar Walton’s “Bolivia” in the importance of a continuing bass vamp to establish a signature rhythm, “Bogota” proceeds as Jamal sprinkles bright treble-clef notes over the energetic percussiveness. Then the piece switches to a major key with walking bass lines for Jamal’s characteristic improvisation, swinging with powerful bass-clef chords, orchestral accents, and spiraling 64th notes. The piece ends with a restatement of the melody over Nasser’s vamp.

The CD includes two popular songs from that concert: “Lollipops and Roses” from Jack Jones’s 1962 recording; and “Tangerine,” introduced in the 1942 movie, Fleet’s In, and receiving much airplay that year from the Jimmy Dorsey Orchestra. Performed perhaps as an audience pleaser, the “Lollipops and Roses” waltz features Jamal’s improvisational mastery in the middle section. Again, his style evinces appreciation of the bassist’s and drummer’s contributions by holding back for Nasser’s solo, the modes switching back and forth from major to minor. “Tangerine” swings at a medium tempo in E-flat major with Jamal’s forceful chorded attacks after the initial minimalistic statement of the melody.

The same 1963-1964 package is completed with selections from Jamal’s April 2,1964 concert: Evans’s “Keep On Keeping On,” Jamal’s “Minor Moods,” and Gershwin’s “But Not for Me.”

With indefatigable brio, Jamal performs “Keep On Keeping On” as a call-and-response with self. The gospel-inspired chords in the first three measures answer the one-bar single-note call as a lead-in and on the fourth measure. That is, until Jamal’s roaring tornadic puissance at 1:50 breaks out into exuberant improvisations through the remaining 7-1/2 minutes, his calm-before-the-storm technique serene until it introduces exciting urgency. Jamal’s waltz, “Minor Moods” in D minor, contrasts melodic upper-register delicacy with sustained-over-the-bar-line powerful two-handed chords. The entire CD package ends with the trio’s lightly swinging version of “But Not for Me”—which isn’t to say that Jamal doesn’t apply strength to create surprise with his heavily accented chords for humorous appeal.

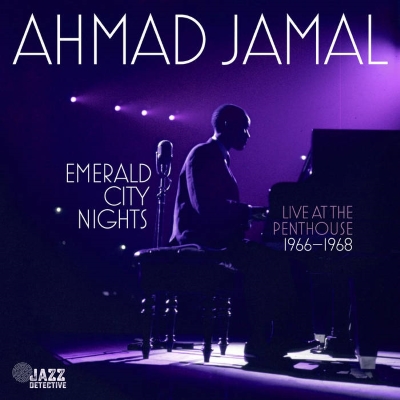

Possessing a treasury of tapes documenting live jazz performances at the Penthouse, Puzzo, Jr. provided more tapes to be mastered from Jamal’s concerts on March 18,1965 and March 25, 1965 with Nasser and Lampkin; October 28, 1965 with Nasser and drummer Vernell Fournier; and September 22, 1966 with Nasser and drummer Frank Gant.

Jamal approved the commercial release of this music too. The result is a second set of CD’s: Emerald City Nights: Live at the Penthouse 1965-1966.

Imagine the difficulty of choosing the best tracks from such an abundance of virtuoso playing.

Starting with “I Didn’t Know What Time It Was,” the 1965-1966 recordings include cover songs, except for Jamal’s composition, “Concern.” Establishing the harmonic underpinnings of “I Didn’t Know What Time It Was” with a ruminative rubato introduction, Jamal sets up his dynamic contrast with two fortissimo three-chord pounces followed separately by Nasser’s and Lampkin’s solos. Teasingly, the trio follows with a frolicking straightforward version until those same call-and-response pounces and solos evolve into the thrillingly fast interpretation that follows for the remaining nine minutes. Then at 12:58, the light-hearted whimsy returns. Until the aggressively accented three chords and bass and drum solos return, in yet another contrast to the preceding section, as the outro.

The remainder of the first disk of the 1965-1966 set consists of a suite of songs from Anthony Newley and Leslie Bricusse’s play, The Roar of the Greasepaint – The Smell of the Crowd.

“Who Can I Turn To?” starts with Jamal’s sustained arpeggios. Yet again, he follows calmness with agitation, long tones in dynamic difference to the succeeding force of broad fortissimo chords from :38 to :45. Like “Poinciana,” “Who Can I Turn To?” dependent upon soft textures and inviting, rumbling percussiveness, proceeds serenely after the high-intensity chords, as if, drolly, the unexpected contrasting vigor were a call for attention from the audience. Jamal’s tribute to the play continues with “My First Love Song.” After Jamal’s tender and supple rubato intro, his pauses ornamented by coruscating upsweeps, Nasser’s arco bass singing in long tones, the trio shifts gears to play the song with a medium-tempo walking-bass swing, Jamal’s accents characteristically and friskily offsetting the light swing. The suite concludes with a soulful version of “Feeling Good.” Nasser and Lampkin add the vamp-driven background textures to Jamal’s spontaneity, which includes rippling re-harmonizations, extensions of phrases, and allusions to “The In Crowd” and “Blues and the Abstract Truth.”

On the second disk, Jamal performs “Poinciana” with swaying spirit in D minor on the second disc of the Emerald City Nights: Live at the Penthouse 1965-1966. No doubt, Jamal includes that crowd favorite in every concert, and perhaps not with hesitation. For Jamal said, “I knew I had something” [with his version of “Poinciana”], and he refused to play it public until Malcolm Chisholm recorded it. Interspersed with phrases from the famous recording (along with the quote from “I’m Glad There Is You”) is Jamal’s free improvisation. The growing energy of Nasser and Gant suggests that the trio, joyous and cohesive, was totally engaged in the performance.

Vernel Fournier, who famously played drums on the 1958 recording of “Poinciana,” appears on two tracks of the October, 1965 concert. Jamal’s “Concern,” built initially on descending fifths blooming subtly into broader chords, moves into a medium-tempo swing (quoting bits of “Fascinatin’ Rhythm,” “No Moon at All,” and “Surrey with the Fringe on Top,” among other allusions). “Like Someone in Love” starts with Jamal’s free introduction, until the melody emerges over Nasser’s pedal point (and of course, includes quotes, this time from “The Sound of Music” and Ferde Grofé’s “On the Trail” from the Grand Canyon Suite).

The 1965-1966 package ends with a jubilant, prestissimo 3-minute version of Benny Golson’s “Whisper Not,” the melody disguised amidst the furious improvisations of the trio until it emerges more declaratively in the fifth octave register. Abandoning recognizable melody again, the trio resumes rapidity and force as Jamal’s left-hand chords—played as half notes, each with shifting colors of internal harmonies—recall Garner’s influence and Ted Nash’s observation about the uniqueness of Jamal’s comping. Then, in the midst of Jamal’s against-the-rhythm thick chords, the track fades.

The jazz listening public awaits the third package—Ahmad Jamal’s Emerald City Nights: Live at the Penthouse 1966-1968—to be leased in the future. The trilogy then will be completed.

Give them time. At least the first two volumes, never before released, are available to be savored after a wait of more than half a century.

Artists’ Web Site: https://ahmadjamal.com

Label’s Web Site: www.deepdigsmusic.com

www.thejazzdetective.com