Kansas City musicians riff on proposed label for a favorite genre.

Special to The Star

By BILL BROWNLEE

Not a single note was played in the creation of the most consequential jazz-related story of last year.

A furious torrent of incendiary blog posts and tweets by musician Nicholas Payton is forcing musicians and fans to reassess their relationship with the music. Among other things, Payton insists that the word jazz is racist and that deeply embedded societal oppression of black Americans necessitates a reclassification of the music.

Recent discussions with three prominent local jazz musicians — Bobby Watson, Clint Ashlock and Hermon Mehari — offer insights into the theorizing that has roiled the jazz community. All men have interacted directly with Payton. Each expressed surprise at the provocative tone he’s used.

While the men take exception to portions of Payton’s campaign, all respect his intellect.

“He’s come up with a succinct way to say a lot of things,” Mehari, 24, a trumpeter and one of Kansas City’s brightest young stars, says of Payton’s Twitter feed. “And the blog posts are very Zen, very thought out and very philosophical in nature. It’s really deep.”

Payton, 38, is one of the most exciting jazz artists to have emerged in the past 20 years. He made his name by adeptly adding to the jazz legacy of his hometown of New Orleans even as his music has grown increasingly progressive. Payton has displayed his trumpet prowess at the Folly and the Gem theaters in Kansas City, and around the world. His most recent area appearances were at the Mutual Musicians Foundation and at the Rhythm & Ribs 18th and Vine Jazz and Blues Fest in 2010. He also contributed to the soundtrack of the 1996 Robert Altman film “Kansas City.”

Such impeccable credentials added to the shock value of Payton’s suggestion that “jazz died in 1959.”

In a provocative November blog post titled “Why Jazz Isn’t Cool Anymore,” Payton declared that “the Golden Age of Jazz is gone” and that “jazz is a marketing ploy that serves an elite few.”

Traditionalists may think he’s a cranky provocateur, but he’s actually a fierce defender of the music’s heritage.

“I think he is very divisive with his comments,” says Ashlock, 31, a trumpeter, composer, bandleader and educator who lives in Lenexa. “Even though I believe he means well for the music and all who play it, his stance, which he’s completely entitled to, comes across as very angry.”

It’s no secret that jazz is struggling.

Locally and nationally, the audience is shrinking and venues are working hard to remain open. That’s why many feel that Payton’s discourse is particularly ill-timed. Others believe that the concepts espoused by Payton directly address the problems at the core of jazz’s increasing lack of popularity and could lead to the music’s commercial revival.

“It’s extremely helpful,” Mehari says of Payton’s proselytizing. “And I would venture to guess that the guys pushing the music forward right now agree with what he’s saying.”

Having grown up in an era dominated by hip-hop, Mehari is part of a generation of jazz musicians with little emotional allegiance to the jazz label. While Payton’s suggestion that jazz might be more accurately titled “black American music” initiated a firestorm of debate, Mehari endorses the proposal.

“I think economically we’d be better, and I think we’d be musically better, too,” Mehari says.

Mehari, like many of his contemporaries, insists that the word jazz is inherently restrictive.

“When you’re trying to create, you don’t want to be limited,” he says. “The jazz label limits the art, it limits what’s really happening.”

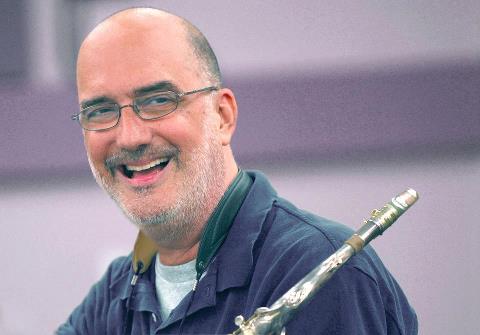

Watson, 58, director of jazz studies at the University of Missouri-Kansas City Conservatory of Music and Dance and an internationally acclaimed musician and composer, has mixed feelings. While he admits that “the word jazz is like kryptonite” to many potential listeners, he also believes that “it represents tolerance.”

In spite of his reservations, Watson sides with Payton.

“I told him, whatever you want to call it, I’m a part of it,” Watson said.

Watson and Ashlock also believe that trading one label for another could be an exercise in futility. Yet it’s not merely a matter of semantics. Many of the same issues that have long troubled the United States are at the core of Payton’s philosophy.

“Nick’s entire argument is based on the assumption of racism,” Mehari suggests. “He believes that blacks in this society are born into a place in which they’re not on equal footing.”

Ashlock concurs.

“Racial issues are definitely not gone,” Ashlock said. “But it seems to me like the musicians I respect are playing music that is inclusive, not exclusive.”

The inclusive nature of jazz — a form that celebrates improvisation — mandates its ongoing progression. Fueled by waves of students educated at Watson’s program at UMKC, Kansas City’s scene is undergoing a dramatic transition. An almost incomprehensible variety of music is being performed under the nebulous label of jazz, a situation that continues to confound casual listeners.

The genteel swing of Tim Whitmer is dramatically different from the adventurous aesthetic of the People’s Liberation Big Band. The sonic aggression of Snuff Jazz is universes removed from the soul-based vocals of Ida McBeth. Yet all are categorized as jazz.

“People don’t realize how wide and how broad the word jazz is,” Watson said. “Being a jazz musician means that I can play anything.”

Watson’s former pupil, Mehari, includes hip-hop and pop dates on his performance schedule.

“The tradition has always been to move forward,” Mehari said. “You can enjoy the past. You can learn from the past. But Nicholas said, ‘Don’t be stuck in the past.’ I don’t want people to define my music as jazz, I want to be defined as Hermon Mehari.”

Whatever directions the music takes, social media are sure to continue to play a major role. Earlier this month Mehari and a handful of jazz and hip-hop musicians collaborated on a video featuring an affectionate jazz-based cover version of a recent Jay-Z and Kanye West hit. While lighthearted, the recognition that social media savvy can reach an audience of millions will almost certainly continue to motivate similar cross-genre vents.

Watson isn’t convinced of the efficacy of social media.

“If (John) Coltrane was still alive would he be on Facebook?” Watson wonders.

Watson insists that it’s the quality of the music that matters. And for his part, Payton’s not shy about his talent.

“There is no living soul who can walk on a bandstand anywhere in the world and play more horn than me,” Payton wrote in a December blog post.

An outspoken admirer of Payton, Watson suggests that Payton might be best served by focusing on his music.

“Nicholas is a force to be reckoned with,” Watson said. “The most powerful thing he can do is just keep playing that horn.”

Read more here: http://www.kansascity.com/2012/01/13/3367081/a-controversial-proposal-would.html#storylink=cpy