At first frustrated by the COVID pandemic’s obstacles blocking musicians from recordings and concerts, drummer Gerry Gibbs decided to find a way, or ways, to overcome them. His determination evolved from the sudden frustration that stalled his planned 2020 album release to the unanticipated inspiration that led to the album of his lifetime.

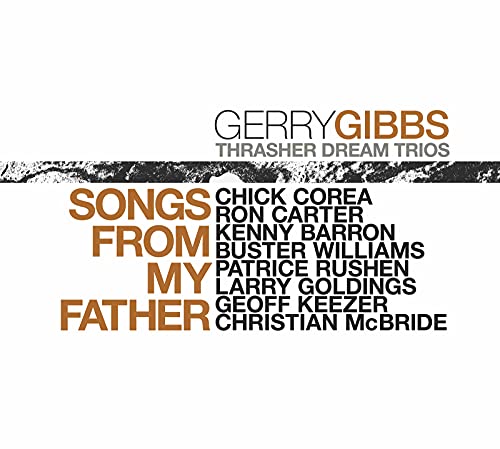

Gradually, Gibbs’s Thrasher Dream Trios album took shape as a way to honor two important musicians in his life: Chick Corea and his father, Terry Gibbs.

Unexpectedly, Corea took an interest in Gibbs’s unshaped projects, and he contributed ideas, a composition, and four of the double-CD’s 19 performances. Corea remembered that bebop vibraphonist Terry Gibbs hired him when he was but a teenager. Participation in the arrangements and performances for the album represented his way to pay back for the elder Gibbs’s interest in Corea at the early stage of his remarkable career.

Not wanting to play merely standards after struggling to record in an age of social distancing, Gibbs sought original compositions for the projects, and then—eureka!—he, along with others, decided that a tribute to his father would be the perfect theme.

Terry Gibbs modestly states that he wrote songs with chord changes that he had fun with on the vibes; he had no thought of others recording his music. No one knew better than the son that his father had written hundreds of songs over his career of 70-plus years as he worked with jazz icons. The difficulty would be winnowing down all of those pieces into 19 tracks on Songs From My Father.

Once Corea was on board, along with legendary bassist Ron Carter who completed the trio, the drummer decided to add three more pianists, even though they lived far apart. Gibbs’ solution? He went to them. He and his wife drove over 15,000 miles to record the tracks for the double album.

The result is an album of virtuosic performances, spurred no doubt by the ability to experience the joy of recording jazz again, still during a pandemic, not to mention invigorated by the opportunity to provide musical appreciation for the 97-year-old Terry Gibbs’s long jazz career. The joy is so overwhelming that it comes through on every track of the recording.

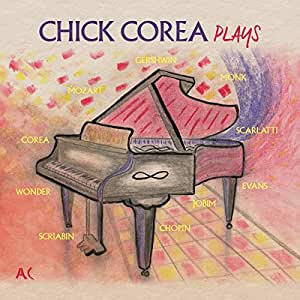

Gibbs didn’t know until after the album was finished that it was Corea’s last, and it inadvertently commemorates one of jazz’s legends. Poignantly, while Corea wrote the final piece for the album, “Tango for Terry,” the album also includes the honoree Terry Gibbs’s 1961 song for Corea, “Hey Chick.”

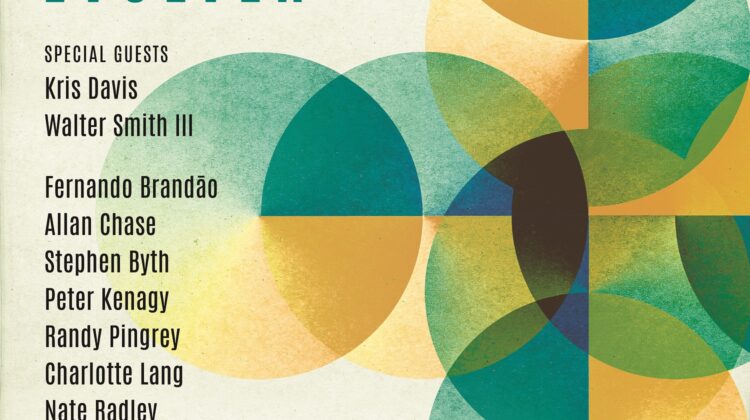

Settling for nothing but first-call musicians, Gibbs’s other Thrasher Dream Trios consisted eventually of pianist Kenny Barron and bassist Buster Williams, pianist Patrice Rushen and Hammond B-3 organist Larry Goldings, and pianist Geoff Keezer and Christian McBride. The tracks are roughly evenly split with four or five by each trio.

First, an appreciation is deserved for the effort that went into “Hey Chick.”

Gerry Gibbs’s idea was to summarize the scope of the project, and to pay tribute to Corea’s vitality, in this one track through a feat of sound engineering by Mike Marciano. And so, all the musicians but Corea improvised with enthusiastic professionalism upon the theme, Keezer /Carter providing the lead-in and Keezer /McBride completing with the final chorus. Ingeniously, the track starts the rounds of improvisations with Terry Gibbs’s 1961 recording, enhanced by fills from Gerry Gibbs and Goldings.

And then Corea’s reciprocal composition, “Tango for Terry,” perhaps his last, finishes the album in purely Corea-ish style with those trademark accents, Spanish allusions, stirring rhythms, broad characteristic chords, twinkling grace notes, minor-key expression and his ageless musical scamper. Unlike Terry Gibbs’s bebop-inspired melodies, “Tango for Terry” instead shares Corea’s musical personality on the album for a final remembrance.

Songs from My Father consistently inspires exceptional performances by all the Thrasher Dream Trios.

Corea’s choices appear to be in line with the themes of his earlier albums. Gibbs’s “Waltz for My Children” recall his 1983 ECM album Children’s Songs. Instead of being influenced by Bartók, this time Gibbs provides the inspiration with a gently flowing waltz that Corea plays with his well-known bright shimmer. And there’s “Bopstacle Course,” which Corea, backed by Carter, plays with effortless bebop chops, and “Sweet Young Song of Love,” arranged again as a My Spanish Heart-liketango such that only Corea would be recognized as the performer.

In addition to Carter, the elder statemen of the recording, Kenny Barron and Buster Williams, perform a mixture of contrasting Gibbs’s compositions too, from the album’s first track, “Kick Those Feet”—played a medium fast tempo that engages all three instruments in a rousing swing—to the largo, beautifully crafted, pensive “Lonely Dreams.” And once again, Barron and Williams contribute unforgettable performances that are reminders that they immerse themselves completely in the music when they play.

Speaking of immersion in the music, Geoff Keezer with Christian McBride amaze with their thrilling prestissimo version of “Nutty Notes,” played with Tatum-like quickness and precision, all the while injecting humor into the piece. Continuing to choose Gibbs’s humorous pieces, this Thrasher Trio plays “The Fat Man,” a medium-tempo blues played with broad chords at a second-line rhythm that glides into a straight-ahead walking-bass section allowing McBride, and then drummer Gibbs, to solo. On the second disc, the trio returns to fast tempos with “4 AM,” connecting all three musicians in a frolic involving flurries of notes leading to sudden stops. And they capture the spirit of Terry Gibbs’s music too on “For Keeps,” a catchy melody written for foot-tapping infectiousness (but notice Keezer’s complementary but differing lines, long in the left hand and darting in the right), and “Gibberish,” which features an extended McBride solo.

The fourth Thrasher Dream Trio includes not upright bass, but Goldings on the Hammond B-3, which lends a groove to some of their tracks while providing the bass lines on the pedal. “Smoke ‘Em Up” lives up to its title with Golding’s Dr. Lonnie Smith-like soulfulness, Rushen engaged in head-bobbing staccato treble chords and anchoring bass notes. “Hippie Twist” starts with Goldings’s call-and-response motive, responding to his own call or then Rushing responding with an ebullient upsweep or cascades of notes on the piano. “Townhouse 3” proceeds rapidly with a melodic hook and vibrancy in a fast, exhilarating samba that allows for Gibbs to provide “talking,” “laughing” celebratory percussion, apparently on a cuíca. Then the trio slows down to a long-toned luxuriant interpretation of Terry Gibbs’s ballad, “Lonely Days,” and then sweeps along with its version of the jazz waltz, “Pretty Blue Eyes.”

While the son couldn’t keep the project secret from his father until the project was finished, Terry Gibbs nonetheless states in the album cover that he is indeed impressed by the exceptional musical quality of the finished album, which consists solely of his compositions from several generations of jazz progress.

Compositions written for himself that the vibraphonist thought that no one else would want to record.

And so, the exasperation that the pandemic causes musicians may be significant, unlike any known before the past two years. But nevertheless, Gerry Gibbs found a way to overcome its barriers and develop the album of which he is most proud.

And so is his father.

Label’s web site: www.whalingcitysound.com