Music tells the stories of life. More eloquently than can words. For those who will listen. It’s not sufficient merely to hear. For in the stories contained within the notes and even within the rests between the notes played by an accomplished musician, music can capture injustice, joy, struggle, love, hope, loss, wonder, war, celebration and…well, any human experience that affects the heart. The ability to attain a deeper level of feeling after transcending technical learning leads to the exploration of beauty that, after all, is the ultimate basis for music. The Greeks worshipped Euterpe, their muse for music and lyric poetry, who can still represent the search for beauty through music.

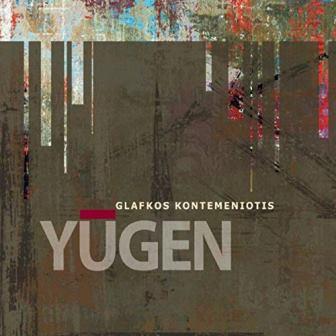

Jazz pianist Glafkos Kontemeniotis has quite a story to tell, and he tells it now in his recent album, Yūgen. The title refers to a Japanese aesthetic that admires the inexplicable beauty of the world contrasted with the human suffering within it. Ironically enough, Kontemeniotis found the word, ineffable but appropriate, to describe his early conflicting experiences of artistic wonder and the dangers of military invasion. Yūgen captures the quest to reconcile these differences as it describes in musical terms no less than the course of Kontemeniotis’s life. At the age of five, he found himself trapped in the Turkish invasion of Cyprus. That island’s history is centuries old. Since 1100 B.C., its majority population has been Greek, which is Kontemeniotis’s heritage as well, though Cyprus has undergone successive occupiers since then. During the 1974 invasion, hundreds were killed, thousands went missing, and hundreds of thousands, including Kontemeniotis, were displaced on Cyprus. However, Kontemeniotis’s boyhood experiences with the horrors of war were alleviated by the artistic equanimity of his studies of classical music in Greek-controlled Nicosia.

At the age of nineteen, Kontemeniotis moved to New York City, where he discovered jazz. Music provided a positive influence on his outlook upon life, and yet the memories of the potential for conflict remained. Therefore, Yūgen, through music, makes whole the dichotomy of life: the eternally incomprehensible but awesome beauty of nature that contains the sadness and struggles of human life within it.

That’s quite a scope to lay out for a single recording.

Let’s start with the composition, “Yūgen.” Performed at first in the manner of a folk song simply without chords in the middle range of the piano, Kontemeniotis’s treble-clef solo melody receives eventual spare counterpoint from the lower register that forms the basis for the composition. After the first chorus, vibraphonist Alexander Gagatsis restates the melody as Kontemeniotis in call-and-response mode weaves the piece into a delicate fabric supported by drummer David Meade’s light clip-clopping pattern of off-the-beat accents. Though in twelve-eight, the placement of unexpected accents adds tension to be resolved at the elegant conclusion, expressed by saxophonist Joel Frahm’s final coruscating glissando.

An album of original compositions, Yūgen continues Kontemeniotis’s unique exploration of personally revelatory themes with “Catharsis,” also a minor-key gem, but one that, after a moving solo introduction, glides quickly into six-eight joyfulness. It becomes clear how important to Kontemeniotis Yūgen is as he lets be known the eventual supremacy of art’s ethereal connection to wonder over human distress through the device of a recollection of intense childhood fears released: that is, the elevation from invasion and displacement to grace. Catharsis indeed, as the other members of the quartet join Kontemeniotis in the piece’s gradual path to celebration.

Frahm’s immersion on soprano sax into the composition’s feeling adds another dimension to the piece. The intensity of his playing–with dynamic sweeps of rising and falling volume and his rightness of improvisatory singing–transmits the happiness that resulted from Kontemeniotis’s journey. In fact, Kontemeniotis has assembled, no doubt with care, an quartet that understands his artistic intentions and expands upon the distinctive nature of his style. Frahm has recorded his own discography of acclaimed albums, as well as participating as a sideman in over a hundred CD’s, including influential albums such as Kurt Elling’s 1619 Broadway: The Brill Building Project and the breadth of Matt Wilson’s recordings from Wilson’s unconventional early-career project of Going Once, Going Twice to Wilson’s mature elegiac Beginning of a Memory. Then there’s Marcus McLaurine, Clark Terry’s bassist for 25 years, not to mention backing up Kenny Burrell, James Moody, Dizzy Gillespie and, in a surprising contrast, often with Kool & The Gang, A teacher for thirty years in New York City’s public schools, Meade has squeezed in time to back Aretha Franklin, Wayne Shorter, Nancy Wilson and Larry Coryell. In addition, vibraphonist Gagatsis, also with a Cypriot residency, plays on four of Yūgen’s tracks and shares Kontemeniotis’s cultural background, Gagatsis’s mutual feeling for the music evident in the liner notes he wrote. And vocalist Eleni Arapoglou, herself an Athenian native and Berklee University of Music graduate, leads soulfully the melody of “Dingane.”

“Dingane,” by the way, adapts McCoy Tyner-like fierceness and his signature chordal style to the storytelling that again evolves from a poignant solo introduction. Then the entire group joins in a twelve-eight narrative told by the rhythm section’s nudging accents, Kontemeniotis’s tremolos and dense chords of adjacent notes, and Frahm’s spirited beseeching–all in a naturalistic atmosphere.

No doubt, the catharsis of Kontemeniotis has found release in the quirkiness, in the freedom, of Thelonious Monk‘s music, for two of Yūgen’s tracks expand upon Monk’s originality of style. First, Kontemeniotis plays “A Monk Met a Goat,” and who knows why Kontemeniotis chose a goat for the piece’s fanciful visualization of what would have actually happened if Monk had met a goat. Nonetheless, after Kontemeniotis’s dissonant, thoughtful start in the lower and middle range of the piano, the quartet, freed from standard jazz conventions as was Monk, explores the possibilities of fun that music allows. Frahm summons the spirit of Charlie Rouse to revel in the joys of Monk-like metrical displacements and then a fast-paced bovid chorded blues. And then, naturally, “A Monk Met a Cow” follows. Of course. Kontemeniotis’s solo left-hand loping motive of bovine inspiration evolves into sweeping single-note and unconventionally chorded treble-clef responses. Kontemeniotis’s “Improvisation” is a pensive in-the-moment composition of Mediterranean origins that he plays calmly and quietly without rooted resolution within the middle register of the piano, possibly as a meditation upon the sacrifices of his recently deceased mother, Stella Spyrou.

But “Improvisation’s” hesitant introspection leads to the conclusion of Kontemeniotis’s cathartic journey of thought and experience as he concludes Yūgen with “Hope,” that eternal wish for betterment so that others may benefit from the experiences of the past. “Hope” indeed is expressed as an uplifting composition of Kontemeniotis’s enjoyment of the tension and release of a meter of three against four. But the section between swaying choruses of the singing quality from Frahm’s soprano sax and the piano’s upper register provides a wish for freedom, beauty and a musical hope for humanity’s goodness worthy of the world’s beauty.

Artist: www.glafkosjazz.com