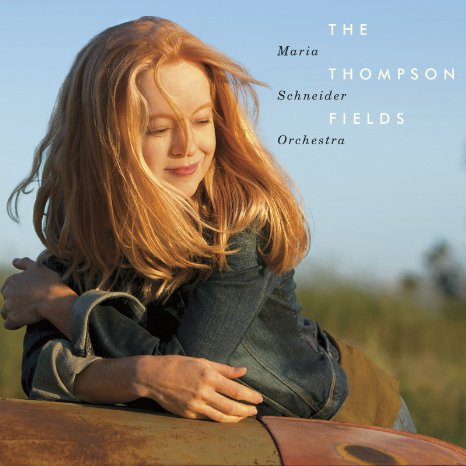

The Maria Schneider Orchestra has returned after eight years. Certainly a cause for celebration, the orchestra’s album, The Thompson Fields, wildly exceeds expectations.

The Thompson Fields may end up as being considered Schneider’s signature achievement—the work that captures not only the incomparable sound of her orchestra in all of its subtle shades and gorgeous colors, but also the one that makes clear that Maria Schneider’s heart drives her music. The musicians who love what they do and peel away layers of extraneous compartments to bare their souls in their achievements are those who transport listeners to a higher level of feeling consciousness.

Maria Schneider knows how to do that. She is fully aware of the power of music to heighten a person’s experience, if that person allows it to happen. Schneider implies so in the liner notes for The Thompson Fields. She remains constantly aware of one essential element, not just in art, but in life: beauty.

In fact, Schneider is in awe of beauty, an abstract truth that infuses her music and makes it special. So special that a half century from now musicians may still be studying her works in ways similar to her and Ryan Truesdell’s veneration of Gil Evans. Without realizing it until her maturity, Schneider had a childhood environment in the fields on Winona, Minnesota, that infused her with the beauty that characterizes her music. Eventually, Schneider took that beauty to New York and then to the world, where listeners have benefited from it. How proud Schneider’s parents must have been to hear their influence expanded to such degrees of magnificence.

In her short essay for “The Monarch and the Milkweed,” Schneider writes: “What I’m expressing is a big mystery anyway. The subject is beauty.”

She goes on. “What is [beauty] exactly, and why does it exist? …Who is the decider of what’s beautiful? …Could relationships within the natural world revolve partially around an attraction to beauty?” And so, through her music, Schneider is addressing more than tones and rests and chords and harmonies and improvisation and melodies. She is involving her soul, her self, which in turn considers the eternal wonders of truth, decay and regeneration, weather patterns, family, means of communication, cycles of nature, beauty, and art.

Schneider’s fulfillment of her fascination with beauty arises from the performance of her own works by her orchestra, her means of expression since 1993, when she astounded jazz listeners with her originality by presenting her own ideas about the sound of a jazz orchestra. And now, with The Thompson Fields, she has organized those ideas around a central theme, one that has been with her all her life.

The Thompson Fields also exceeds expectations with its packaging. The CD itself becomes a component of a lavishly produced 55-page hardbound book containing Briene Lermitte photographs of Windom’s farms, Audubon bird paintings, historical maps of the Midwest, excerpts of essays about art and nature, track descriptions, appreciation of orchestra member’s contributions, crowd-funding thank-you’s, and no less than Schneider’s beliefs about beauty.

But the music.

This review, and Schneider’s CD package, include more content than only musical description because her project is larger than the music itself. It rises into the realm of artistic achievement. Thereby, again, wildly exceeding expectations.

The Thompson Fields opens with Scott Robinson’s unique and affecting interpretation of Schneider’s “Walking by Flashlight,” a composition of unabashed Americana that she included in her recorded song cycle, Winter Morning Walks, sung by Dawn Upshaw. Schneider treats her orchestra members like family members and she knows their voices. Writing the piece with Robinson’s sound in mind, Schneider chose his alto clarinet voice, an instrument rarely used in jazz bands, but one that attains clarity, subtlety, natural verisimilitude, ease and underlying passion. The instrument matches the mood of the piece as one that exhibits Schneider’s search for just the right timbre for the performances of her works. Quiet and ruminative, “Walking by Flashlight” itself attains the cadence of reading a poem but without words. Working the colors of her orchestra like an artist, Schneider beings the piece calmly with pianist Frank Kimbrough’s quarter-note pattern and accordionist Gary Versace’s almost imperceptible sustained note before Robinson’s also clarinet sings the melody. Gradually, as if joining the walk, bass, guitar and trombones softly enter. Almost unnoticeably, the orchestra emerges and expands the sonic spectrum until the piece, without percussiveness, attains majesty. “Walking by Flashlight,” sonically cinematic, becomes a succinct, representative and evocative piece suggestive of discovery and wonder.

The title piece refers to her neighbor’s farm, which brings back the waves of memories serving as touchstones for Schneider’s compositions. Like “Walking by Flashlight,” “The Thompson Fields” not so much abandons jazz language as finds it incidental to the recollection of farms and fields and birds and nature. While both compositions end solidly on tonic chords, “The Thompson Fields” adds a twist of bitonality eased in by pianist Frank Kimbrough as if a smaller voice were speaking amid the orchestra’s larger swelling and contrasting sound.

As always, Schneider applies gorgeous textures and colors to “The Thompson Fields” with the same masterful touch that one would expect on “Home” as well. However, “Home” refers to a second home, or maybe a third or fourth one, the Newport Jazz Festival, and it constitutes an appreciation of its founder, George Wein. The piece reconciles its dual purposes of fond memorialization and the improvisational freedom represented by the festival—and by jazz itself—Schneider provides a rich orchestral foundation, unhurried with her trademark broad sonic spectrum, for Rich Perry’s extended tenor sax solo, alternately pensive and impassioned, alternately stirring up tension and releasing it into the orchestra’s landscape.

Schneider’s fascination with birds continues on The Thompson Fields. The book containing the CD is replete with richly colored drawings of birds and vivid descriptions and learned ornithological studies. No doubt the music of birds was the first that Schneider heard, inspiring her as it did Eric Dolphy and others, and it remains throughout her career, and her life. During “Cerulean Skies” on her Sky Blue album, Schneider’s musicians were charged with imitating birds on their instruments, an idea derived from her thoughts about nature and its imperatives for avian migration. In The Thompson Fields, Schneider’s love of birds receives due appreciation on “Arbiters of Evolution.” In that piece, she musically considers the effectiveness of the brilliant colors of male birds of paradise, as well as their extravagant movements, for attracting females, who are the deciders of the species’ paths of evolution. Buoyant and jaunty with non-standard metrical patterns, “Arbiters of Evolution,” unexpectedly, employs the entire tonal breadth of the orchestra—especially the tenor range of the trombones, which state the theme—and not just the upper treble range associated with birds.

More playful, but no less wondrous, than most of the works on The Thompson Fields, “Arbiters of Evolution” features, after its first two minutes, a four-minute tenor sax solo by Donny McCaslin of varied termperaments that recall bird calls too. Then, Scott Robinson comes in on baritone sax, at first without the orchestral blanket and then in conjunction with McCaslin and guitarist Lage Lund as all three engage in a bird-like colloquy of wavering conversational, squawking quarter tones amid the melody.

“Nimbus” puts to music the experience of Midwestern storms with their ominous approaches and sometimes violent arrivals, captured by Steve Wilson’s extended solo of constant agitation and force before dissolving into near silence with Kimbrough’s sprinkling of upper-register notes. Schneider chose to dramatize the fierceness of perhaps a tornado, but certainly a storm of note, with Kimbrough’s minor-key introduction of tremolos, reminiscent of melodramatic silent movie accompaniment, before clarinets and trombones state the theme in rubato fashion with ascending scales and klezmer-like ornaments. Wilson then completes the scene that the orchestra experienced in person when it performed for a concert in Schneider’s home town.

On the subject of family, Schneider deals with the hurt of the loss of a family member from her orchestral family, trumpeter Laurie Frink, in her composition, “A Potter’s Song.” In respectful remembrance, Schneider considered another of Frink’s interests besides music, her interest in ceramics, thereby honoring her whole personality, and not just her participation in the orchestra through the mention of Frink’s solos or tone, etc. Instead, Schneider crafts a gorgeous piece that features heart-felt solos by two other musicians with long jazz associations with Frank: accordionist Gary Versace and trombonist Keith O’Quinn. The entire album, and that, would be…

…but beautiful.

2015

Artist’s site: www.mariaschneider.com

Label’s site: www.artistshare.com