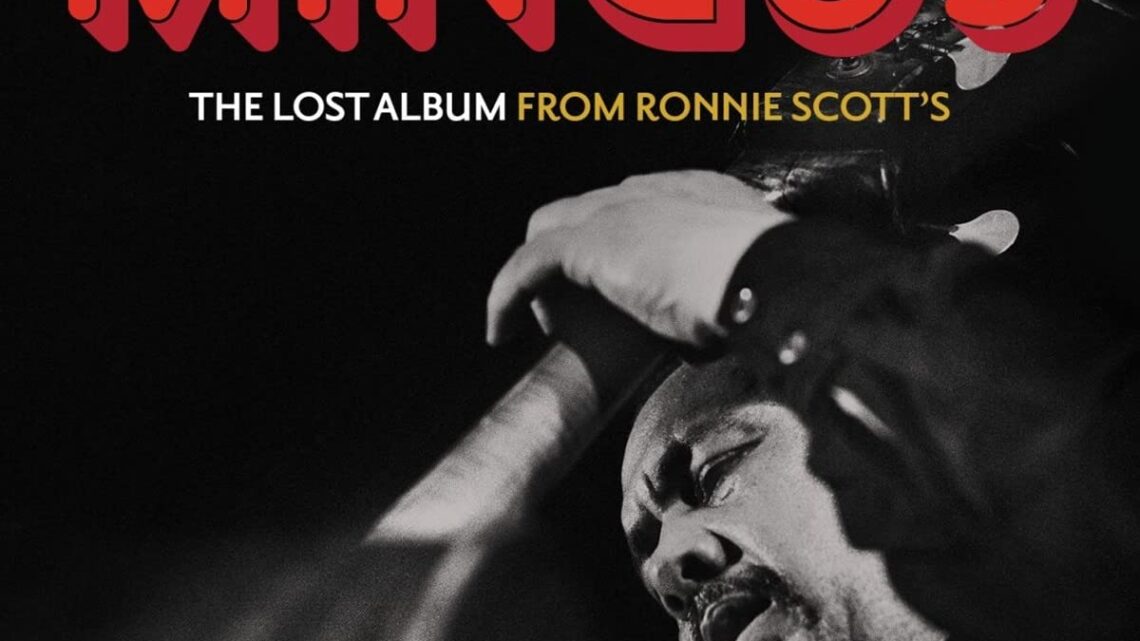

This time, the Resonance Records producers, dedicated and fastidious as is their wont, worked against a deadline to release yet another one of their always-significant albums of previously recorded, but until-now unknown to the public, masterful jazz performances.

The deadline? April 22, 2022.

The performer? Charles Mingus.

The occasion? Mingus’s one-hundredth birthday on that date.

The venue? Ronnie Scott’s Club & Bar in London.

The year? 1972.

The significance? Documentation of Mingus’s work after his re-emergence from his withdrawal from public life.

Further significance? The opportunity to hear another configuration of Mingus’s band with musicians replacing some of his traditional musicians like Jaki Byard, Lonnie Hillyer and Dannie Richmond.

Even more significance? The enjoyment of hearing for the first time a new Mingus recording with all the excitement, force, and one-of-a-kind achievement of his landmark albums.

The producers? Resonance Records’s George Klabin and Zev Feldman, with assistance from David Weiss, Zak Shelby-Szyszko, and Zachary Kirsimae.

One can wonder how long the production period for this as-always remarkable Resonance Records project was as the producers backdated the production of Mingus: The Lost Album from Ronnie Scott’s from 2022. Feldman notes that the idea for its production started in 2011 during a conversation with Sue Mingus.

The process appears to have picked up speed in 2021 when Feldman conducted several of the interviews included in the package’s booklet, as well as when he wrote its prologue.

British jazz journalist Brian Priestley wrote an insightful essay for the liner notes, which also include Priestley’s 1972 interview at Ronnie Scott’s with Mingus and alto saxophonist Charles McPherson.

As always, the Resonance Records package includes insightful information about the artist whose discovered music the label releases. For instance, Sue Mingus’s recalls that Charles’s arrest in Copenhagen led to the cancellation of his gig on the ocean liner back to the U.S. Also, the liner notes dispel the rumor that, as a continuation of his antagonism of reedman Bobby Jones throughout the tour, Mingus pushed him down a flight of stairs. The truth is: Jones fell entirely on his own.

What better way to honor one of the twentieth century’s most important and original jazz composers/band leaders/instrumentalists than to issue a professionally recorded album set in a live environment from an insufficiently documented period of Mingus’s career? Mingus was entering his “elder stateman” phase—although no one could consider him to be someone as sedate as the phrase connotes—when, in the nineteen-seventies, he received the Guggenheim Foundation fellowship, when his struggles were rewarded with a move from jazz clubs to a concert at Carnegie Hall, when his autobiography was published, when he returned to The Newport Jazz Festival, and when Alvin Ailey choreographed the ballet, The Mingus Dances.

After the European tour’s slow start, which experienced the loss of Byard and Richmond who returned to America, Mingus and his new band were on fire throughout the entire set at Ronnie Scott’s Club & Bar.

Though Sue Mingus attributed Mingus’s initial lethargy during the European tour’s performances to strong medications, somehow Mingus overcame their effects by the time he was in London during the band’s last of two engagements at the famous jazz club. The intensity of the band’s performances never flagged, as documented on the three CD’s included in the Resonance Records package.

The aggressive, singularly intense Mingus, whose emotional turmoil was reflected in his music, had returned!

(Proof of his turmoil? In the liner notes, Fran Liebowitz humorously remembers that Mingus left the bandstand in the middle of a set at the Village Vanguard to chase her down Seventh Avenue. Eventually, she had to remind him that his band was still on the stage waiting for his return.)

The recordings of Mingus: The Lost Album from Ronnie Scott’s rank with the highest achievements of his career.

Columbia Records had planned to release a recording of the concert on vinyl. Accordingly, a sound truck with professional recording equipment sat outside Ronnie Scott’s. However, in 1973 Clive Davis—yes, the Clive Davis who produced records by Whitney Houston, Janis Joplin, Aretha Franklin, Earth Wind & Fire, Alan Jackson, Dionne Warwick, and Alicia Keys—released from the label all the jazz artists (including Mingus, Keith Jarrett, Bill Evans, and Ornette Coleman) except for Miles Davis. Fortunately, the eight-track tapes from the concerts at Ronnie Scott’s survived in Sue Mingus’s vault.

Starting the second concert on August 15, 1972, “Orange Was the Color of Her Dress, Then Silk Blues,” at over thirty minutes, confirms Christian McBride’s observation in the liner notes that the blues was the basis for Mingus’s music, even as he explored avant-garde, swing, Latin, stride, and bebop genres. The initial slipperiness and rising slurs in free rhythm distinguish the composition. Roy Brooks’s drums a-rumbling and pianist John Foster slamming out chords and fluttering the tremolos, the piece takes shape at 3:40 when the tempo accelerates and when swing occurs. But not for long. At 4:00, Mingus’s walking bass behind McPherson’s pearlescent tone is just the first change of the ensuing moods, including a rumba (not to mention changes of some abrupt extremes of tempo), that animate the solos. Foster proves himself to be a worthy replacement for Byard, as he combines swing, classical references, blues, glissandi, Latin rhythms, and overall excitability in his extended solo. John Faddis, a prodigy then at the age of nineteen, makes his prodigious talent known. He plays as if he had been a long-time member of the band as he responds to Mingus’s prompts, throws high-pitched darts piercing any listener’s complacency, and leads the prestissimo segments with precise and astounding articulation.

The first disk includes that set’s last number too: “Noddin’ Ya Head Blues,” facetiously entitled perhaps due to its leisurely tempo. Mingus’s virtuosity on bass shines as he introduces the number with a 3-1/2-minute (out of a twenty-minute track) melodic solo that incorporates recognizable elements of the blues, including twelve bars, the flatted seventh, and a narrative quality. Before his solo on piano with quotes like from songs like “Sentimental Journey,” Foster gives Mingus’s instrumental narrative lyrical expression when he sings the bawdy words to the composition with a concluding blues shout: “Some women say they can. / Some women say they could. / If they didn’t have the mister. / I know that every woman would.” Brooks contributes to the memorability of “Noddin’ Ya Head Blues” with his improvisation on the musical saw, quivering and bending tones entirely in character with available down-home musical devices associated with the origins of the blues. At the age of fifty, Mingus, the iconic iconoclast, was still receptive to new inventive ideas that his band members could contribute. After the purity of McPherson’s tone on his blues choruses, Faddis’s indebtedness to Dizzy Gillespie is unmistakable (Mary Scott calls Faddis “Dizzy’s musical son”) as his range rises to thrilling high notes and as Faddis excites with the quickness of his improvised lines.

Mingus introduced “Mind Reader’s Convention in Milano” during the European tour so that, as he stated, he could “make things a little more difficult.” Consistent with Mingus’s classic recordings, this composition mixes varying moods and separate sections, in and out of rhythm, sometimes with free improvisation, and sometimes not, to create his “organized chaos.”Faddis throws Dizzy quotes from “Salt Peanuts” into the mixture while McPherson and Jones interact with their own instrumental cries of joy, desperation, or frustration. Indeed, the piece’s inspiration, personal as some of Mingus’s compositions are, arose from Mingus’s frustration with a promoter in Milan who set up too many microphones, leading Mingus to worry about bootlegging. “Mind Reader’s Convention in Milano” ends with the fury of all the instruments in free cries and then Brooks’s raging drum solo prodding the band’s un-notated screaming responses. After the audience’s applause, the band tears into a supersonic-fast, 45-second interpretation of Charlie Parker’s “Ko-Ko.” The length of “Mind Reader’s Convention in Milano” and “Ko-Ko” consumes the entire second disk.

The third disk offers a more diverse song selection than the first two. It combines a newer composition with some covers and one of Mingus’s famous pieces. Accordingly, the emotional contents of the pieces are in stark contrast. The 35-minutes track of “Fables of Faubus,” whose famous musical phrase Jones starts, proceeds throughout with energetic fierceness, each musician personalizing his own interpretation as spur-of-the-moment improvisation breaks loose. As one of the concerts’ unforgettable performances, “Fables of Faubus” includes solos wild and creative, not to mention technically astounding. Foster smashes and crashes and sprinkles notes throughout his. In addition, “Fables of Faubus” includes a reminder of Mingus’s virtuosity on the bass, not to mention his in-your-face sense of humor when he quotes “Shortnin’ Bread” (which he sings), “My Old Kentucky Home,” and “Dixie.”

Immediately afterward, “Pops,” whose directness and joy are in direct contrast to “Fables of Faubus,” pays tribute to Louis Armstrong, who died the previous year. During this Mingus-ian version of “When the Saints Go Marching In,” Foster does double duty by singing in an imitation of Armstrong’s voice and with a gleeful piano solo. Brooks’s second-line drumming captures the audience’s affection; Jones switches to clarinet to suggest a festive New Orleans street parade; and Mingus slaps the bass at the fingerboard to complete the impression. “The Man Who Never Sleeps” slows down to ballad form as it sets up an occasion for an appreciation of the band members’ tonal clarity, though with a stirring undercurrent, including Foster’s quote of “Stompin’ at the Savoy,” below the sustained notes of the melody. Much call-and-response occurs. The disk concludes with a 1-minute-and-12-second prestissimo version of Benny Goodman/Charlie Christian/James Mundy’s “Air Mail Special,” with brief goodbye solos from Mingus and the horns.

Mingus ends the engagement at Ronnie Scott’s by saying, “Thank you, all you beautiful people, for allowing us to play for you. And thank you for bringing your claps for our recording. We appreciate you. Love.”

Thank you for the artistry throughout Mingus: The Lost Album from Ronnie Scott’s, which wasn’t available until now.

Exactly fifty years later.

And in conjunction with Mingus’s one-hundredth birthday celebration.

Thank you, Resonance Records, for producing it.

Label’s web site: www.ResonanceRecords.org