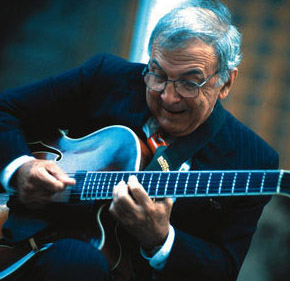

Now that the Grammy Awards are past, it’s heartening to know that artistry, without compromise for commercial enrichment, is recognized. Fred Hersch, whose talent has grown exponentially from the time he arrived in New York in 1977, received, at least, Grammy nominations for Best Jazz Instrumental Album and Best Improvised Jazz Solo. What’s disheartening is the low profile of jazz during the broadcast that values celebrity and ratings at a time when jazz could receive more deserved exposure. Usually the awards for music recorded by any but the top-tier or highly promoted talent are announced before the broadcast itself. Jazz musicians often receive their awards by delivery service. It’s reported that the coordinator for the Grammy Awards once asked Max Roach to “send a current photograph of your group with Charlie Parker” after their reissue won a Grammy.

Still, a Grammy Award bestows recognition and acceptance by an audience larger than that comprising a nightclub’s. But jazz musicians find in nightclubs their most ardent listeners: those who have paid to hear a specific musician(s) in a comfortable environment where the musician is their reason for being there.

Fred Hersch experienced the wonders of a jazz club in his home town of Cincinnati when the spark was lit for his jazz career. And after he moved to New York City, he used to sit on the stairs of the Village Vanguard to hear jazz legends perform because he was too poor to pay for admission. Now Hersch himself has been filling the Vanguard with paying customers, ever since the first performance of his trio there in 1996. And he has recorded four of his albums there. Who knows who has been sitting on the stairs listening to his performances there?

The latest of Hersch’s awaited albums was recorded on a Sunday night—March 27, 2016, specifically—at the Village Vanguard with his trio of seven years. Hersch suspected that something special would happen that night, and it did due to the spontaneity and outreach to an appreciative audience that don’t occur in a studio. Though James Farber recorded the trio on three nights, Sunday Night at the Vanguard presents its entire first set on that Sunday evening.

The opening with “A Cockeyed Optimist” suggests Hersch’s affinity for lyricism and for the ability of song to draw in an audience. Though Hersch’s typically bell-like sound during the piece’s ringing start gives no hint of the song to follow, bassist John Hébert and drummer Eric McPherson join in at the chorus to give the performance fullness and effortless motion. Their presence allows Hersch to launch into a scampering improvisation of the song associated with Mary Martin as Nellie Forbush. Hersch’s understanding of a song’s capacity for connecting with the spirit of an audience is consistent with his work with vocalists like Chris Connor, Mark Murphy, Janis Siegel, Scott Morgan, Norma Winstone, Kurt Elling Dominique Eade and Kate McGarry, as they tell their stories with words and he with notes. Hersch includes on the album another affecting song, Paul McCartney’s “For No One” from the Beatles’s Revolver album—one which he, sure enough, had recorded with Siegel. This time, though, without a vocalist, Hersch glides through the song in mostly the upper register of the piano with his accustomed grace and ease.

Since these songs depend upon strong melodic delivery, one could wonder how Hébert and McPherson would contribute to their embellishment. Hébert does it by rooting the performances with spare, well-chosen notes grounding the songs in the low-register pulse, allowing for Hersch’s spur-of-the-moment meditations and upsweeps. McPherson adds the color and textures, so subtle that one has to listen for his playing, and McPherson’s presence, like Hébert’s, is more felt than heard. The same empathetic accompaniment is true for Jimmy Rowles’s impressionistic, classic composition, “The Peacocks,” where again they remain in the background, making the performance more effective by their unobtrusive presence, however unnoticed they may be, than if they weren’t participants.

With its free improvisation and unpredictable direction like the graphics notation to which it refers, “Calligram” occurs more as an intertwining of equal contributors as all three provide their connected but separately developed ideas. The trio is seasoned enough to keep the performance under control, and with an even volume, as they listen to each other and expand individually upon the others’ ideas.

With his soft cymbal work, McPherson himself sets up the atmosphere for the minor-key “Serpentine” that opens with a unison melodic winding of Hébert and Hersch’s. Eventually, this track does increase in volume as Hersch veers between shadowy imagery and suggestions of an étude. Based upon the changes of “The Best Thing for You,” “The Optimum Thing” represents a challenging exercise in tempo, as the initial spryness evolves into, not an abbreviated, but an extended, accelerating scamper as the improvisations of the three musicians cohere nonetheless by their attentive listening to one another.

As always, Hersch ends the session with a Thelonious Monk tune, and this time it’s “We See.” The playfulness inherent in Monk’s compositions remains an element of Hersch’s musical attitude, as unexpected sprinkles of notes or abrupt, delightful breaks of phrases happen, defying listeners’ expectations of a tune’s direction.

Rising from his initial role of first-call accompanist of the jazz masters to a unique force of jazz piano, Fred Hersch draws upon decades of experience and on an individualistic vision that now achieves due recognition, including his Grammy nomination for “We See.” Most important, though, are his attentive listeners at the Vanguard or anywhere else he performs. Those decades of musical growth will be recalled in his memoir, Good Things Happen Slowly, which will be available soon online or in bookstores.

2017

Artist’s site: www.fredhersch.com

Label’s site: www.palmetto-records.com