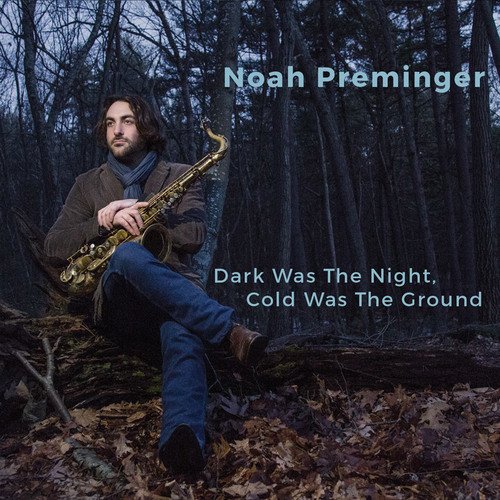

Noah Preminger’s guiding virtue, increasingly evident as his discography grows, is authenticity. A refreshing virtue it is. He states that, in order to avoid trendiness, he doesn’t often listen to recordings. So Preminger’s solution to prevent sounding like everyone else on iTunes’s “Hot Albums” is to shut it out. Nonetheless, on his fifth album, Preminger reinvigorates instrumentally songs of the Mississippi Delta blues, striving to capture on sax and trumpet the voices of its singers.

And so, Preminger isn’t steadfastly opposed to the influence of others, but rather to the detachment from feeling—genuine emotions gained from hard-learned experiences accumulating toward wisdom. Allowing marketing to guide album development—complete with videos, talk show appearances, social media manipulation, contrived celebrity gossip, emotional artifice, trained gestures and elaborately produced concerts promoting the performer’s brand—has led to expensive sameness, and sometimes to handsomely profitable returns. Preminger instead appears to value music that’s real, arising spontaneously from the heart. On Dark Was the Night, Cold Was the Ground, Connecticut native Preminger presents an unexpected choice, the recording venue itself, that being the Sidedoor Jazz Club in New Lyme, in Connecticut, instead of in New York City.

The other members of Preminger’s quartet are equally engaged in the updating of the Delta blues. Benefiting from the long perspective of jazz development, they expand upon the passion of the early blues to include the blazing spirituality and urgency of John Coltrane and Ornette Coleman, among others. While “Hard Times Killin’ Floor Blues” features an unrushed beginning call-and-response of blue notes and conversational cadence, the underlying fire set up by bassist Kim Cass and drummer Ian Froman, initially unobtrusive but compelling, breaks out in the faster and freer middle section. And the middle section is where Preminger and Palmer take the blues sentiment of the early recordings and re-interpret it with free-jazz sensibility, as if telling the same story from a different perspective, before returning to the casual earthiness of the first section.

In fact, the contrast of meters between horns and the rhythm section creates the tension animating the continuing dialogue. For Dark Was the Night, Cold Was the Ground essentially comprises a 53-minute instrumental conversation suggestive of hardship, relationships and spirituality. While the horns represent the voices, the bass and drums, the activity. And so the stories are told with soulful wordlessness, suggesting the path from Mississippi Delta blues to free jazz improvisation.

The playfulness of the blues comes across in “Black Snake Moan,” with its altered quote from “Pop Goes the Weasel.” The horns’ light repeated quarter notes create percussive effect under the other’s long tones, harmonized descent and the ever-present call-and-response. The conversational essence of the genre couldn’t be more evident than in Charley Patton’s “Spoonful Blues,” as the horns growl and lag notes and hesitate as if in thought. And once again, “Spoonful Blues” typifies the convergence-divergence of the group’s division into unity as the horns’ slowness contrasts with the fierce agitation of bass and drums.

On the other hand, the title song engages the quartet in slow mournful meditation, without the turbulence of percussion, as they pay respect to the grief that inspired Willie Johnson’s song. The slowdown into a dirge’s pace allows further appreciation of Preminger’s painstaking attention to tone, including buzzing overtones, as he gives meaning to each note as it’s crafted, like the inflection of a voice that depends the meaning of words. Listeners immediately recognized the individuality of Preminger’s sound, not to mention the originality of his ideas, when he burst into recognition with the release of his first album, Dry Bridge Road, at the age of twenty.

Appropriately, Preminger includes on his new album music that recognizes the spiritual element of the blues. “Trouble in Mind” proceeds with rolling grace through quarter-note triplets in the first chorus. Eloquent, and articulate, blues improvisation merges with the basic soulfulness of the music through the ages as Preminger and Palmer internalize the feel. In contrast, “I Am the Heavenly Way” gets across its spiritual message with a medium-tempo strut that leads into free improvisation of impassioned roiling release that covers the saxophone’s and trumpet’s ranges. Contributing to the group’s ability to effectively capture the vocal quality of the blues on wind instruments is the absence of a chorded instrument, which, other than guitar, wouldn’t have been available for original Delta blues singing. The harmonies, blue notes, deliberate conversational pace, and frequent call-and-response sections emerge with the casual interaction of shared but elaborating thoughts as if Preminger and Palmer were outside instead of in the confines of a jazz club. Consistent with the album’s musical statement, Preminger and Palmer conclude with the benedictory “I Shall Not Be Moved,” which combines, as do many of the tracks, the initial slower tempo that elongates tones at what would seem to be a leisurely pace, but with the propulsive force of the rhythm section. Again, the cleaving of the group into seemingly disconnected halves repairs when the underlying fury of the horns breaks away from their wandering pace and they join the feel that Froman and Cass set up from the beginning.

On Dark Was the Night, Cold Was the Ground, Noah Preminger demonstrates musically that everything old is new again as his group discovered personal relevance in the Mississippi Delta blues. By avoiding the trending ever-presence of the same or similar ideas, which creates a uniformity of messaging, musical or otherwise, Preminger has recorded an album of respectful rediscovery, adaptive individuality and heart-felt meaning.

2016

Artist’s site: www.noahpreminger.com