John Bailey is one of those superb jazz musicians known by other jazz musicians but not so much by the listening public.

That is, not until 2018, when Bailey released his first album, In Real Time. The listening public then became aware of him, for real. It was like, “Where has John Bailey been?”

John Bailey has been everywhere. In plain sight. Even though not playing plainly at all. To say the least.

Where Bailey has been has included work with Ray Charles, Paul Anka, Buddy Rich, Kenny Burrell, Joe Lovano, Ira Sullivan, Woody Herman, Houston Person, Dr. Lonnie Smith, Steve Turre, Randy Brecker, Allen Farnham, Arturo O’Farrill, John Fedchock, Frank Wess, Dave Liebman, Donny McCaslin, Stacy Dillard, Miguel Zenón, Tia Fuller, Cameron Brown, E.J. Strickland, Carl Allen, Bobby Sanabria, Ray Barretto, Wynton Marsalis, Valery Ponomarev, Arturo Sandoval, Cecil Bridgewater, Brad Goode, Don Braden, Gregg August, Harvie S, John Patitucci, Gary Smulyan, Rudresh Mahanthappa, John Di Martino, Bruce Barth, Charles Pillow, Yosvany Terry, and Howard Johnson. And more.

Bailey’s effortless technique, broad versatility, rhythmic flow, burnished tone, right-on pitch, big-band participation, controlled articulation, and imaginative compositional talent combine to form a unique listening experience when Bailey leads his own jazz groups.

His humane domain sustains his strains to entertain with high-octane refrains.

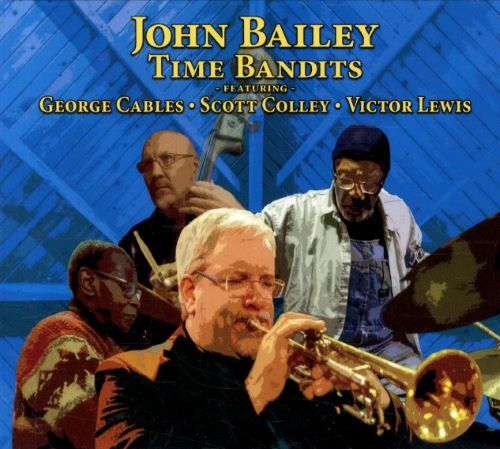

On his most recent recording, Time Bandits, Bailey is leading yet another group of stellar musicians: pianist George Cables, bassist Scott Colley, and drummer Victor Lewis. Unrelated to the classic Monty Python movie, the Time Bandits title instead describes Bailey’s respect for the jazz tradition, which inspired him and from which he respectfully borrows.

The title track starts with a hint of the F-minor swing that follows: four measures of four eighth notes, back and forth, down and back up, between the middle-range F and E-flat. Dotted-eighth- and-sixteenth notes almost imperceptibly substitute for the last two eight notes in the second and fourth measures). That calm solo wake-up-like call to action arouses the other members of the quartet, Cables filling in the final two beats of each measure with his own vamp. Then a full-blown swing session breaks out after the teasing (like, where is this going?) introduction. Time (meter) shifts. Excitement ensues at :57 when Bailey exudes post-bop swing, à la Freddie Hubbard. Cables glides in from lower-register minor-key plunges to a glistening fifth-register solo. An intro of the entire group, “Time Bandits” provides Colley with his own solo of force and precise articulation before Lewis trades fours individually with Bailey and Cables. Each of Lewis’s solos project a separate technique and feeling, the third of the four solos incorporating the initial four-note accents.

The blues that follows, “Various Nefarious,” moves at a medium shuffle in B-flat minor—in contrast to the up-tempo “Time Bandits” swing—accentuated by Colley’s walking bass lines. The track is reminiscent of Maynard Ferguson’s “Foxy” on his Newport Suite album, sassy accents and anticipation of the beat driving the performance. However, the bridge that Bailey wrote, his re-harmonization in the fifth and sixth measures, and his sixteenth-note tumble in the ninth measure (in unison with Cables) individualize the piece. Of course, the extremes of high notes identified with Ferguson aren’t included. Nor are they needed for the group to convey their immersion in the music.

Bailey’s tributes to influential trumpet players continue on “Ode to Thaddeus,” a largo tribute to Thad Jones of the Thad Jones/Mel Lewis Orchestra. Introduced by Cables with an E pedal point anchoring his development of the minor-key theme, Bailey with respectful remembrance plays his gorgeous composition in long tones. He concludes the piece with a shift to G-major, as if from dark to light, D being the final pedal point.

“Lullaby” was Cables’s 1-1/2-minute duo intro to saxophonist Frank Morgan’s 1989 Mood Indigo album. However, on Time Bandits, Cables chimes in with rubato descending fifths, as if creating calmness at the end of the day. Cables and Bailey expand Cables’s composition to 5-3/4 minutes, thereby providing extended serenity in a mood similar to that of “Ode to Thaddeus.” This time, Bailey provides the poignant long tones on flugelhorn, making the textures even more polished. More important, Cables has the opportunity to expand on his theme as a duo this time with Bailey. Eventually, they enliven the rhythm beyond the tenderness of the glowing tintinnabulation. Finally, the piece eventually slows with their call and response and then it fades.

Of personal significance to Bailey is his tribute to multi-instrumentalist Ira Sullivan, who encouraged him at the beginning of his musical career. In fact, Bailey doubles up his trumpet tribute on “How Do You Know?” which both Sullivan and trumpeter Red Rodney played on their 1983 Sprint album. Colley begins the track with a low-key solo presenting with precise pitch the melody in slow, rubato style. For the second chorus, still at a largo pace, Bailey and Cables join Colley in C major with a bright trumpet exposition and lush harmonies. After the pensive introductions, at 1:20 the spirit that moves the entire quartet moves into a medium-tempo light swing. The natural ease and professionalism of the quartet can’t help but be appreciated as they develop musical narratives with their solos, including Bailey’s effective buildup to “How Do You Knows’s?” dramatic ending.

The quartet remains in its balladeering mood when they perform John Lennon and Paul McCartney’s “She’s Leaving Home.” Without true repetition from beginning to end but with a parallel poetic structure, the song contains a story about parents’ feelings of guilt, regret, and loss when an offspring leaves home. “She (We gave her most of our lives) / Is leaving (Sacrificed most of our lives) / Home (We gave her everything money could buy) / She’s leaving home after living alone for so many years. Bye, bye…. / She (What did we do that was wrong) / Is having (We didn’t know it was wrong) / Fun (Fun is the one thing that money can’t buy).” The sentiment is similar to that of “If He Walked into My Life” from Mame: “Though I’ll ask myself my whole life long/ What went wrong along the way / Would I make the same mistakes / If he walked into my life today?” The painful emotions of the lyrics are reminders of Lennon and McCartney’s singular talent as songwriters. Played slowly while uncovering the layers of meaning in the song, Bailey’s quartet plays it mostly in a straightforward manner. The multi-tracking of the performance is the clever technical element, which is even more evident when the lyrics are considered. Bailey plays the “She” and “Is leaving” and “Home” on trumpet, while he plays the parenthetical responses on flugelhorn, the trumpet’s wounded cry stretched out over long tones throughout the responses.

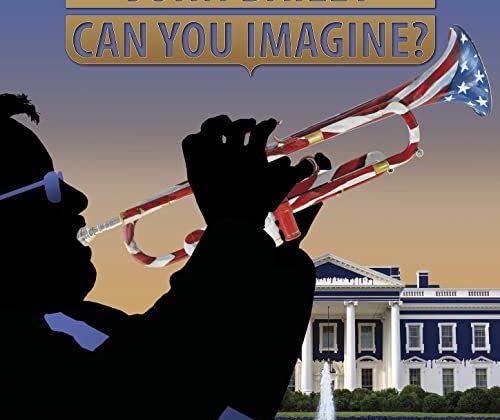

But Bailey—a trumpeter who produced an entire album with the hypothetical situation of Dizzy Gillespie as the U.S. President (“The Humanitarian Candidate” of Can You Imagine?)—can’t be expected to be poignantly reminiscent for long. (My favorite promises from Gillespie’s actual campaign were renaming the White House “the Blues House” and making Ray Charles the Librarian of Congress.) Lewis’s composition, “Oh Man, Please Get Me Out of Here!” provides brief, darted accents and the chance for Bailey to refer to Gillespie in his high-register, familiarly slurred, swinging, and entertaining solos.

Bailey’s “Groove Samba” provides for Time Bandits an upbeat finish, one of the joy and musical cohesion from seasoned professionals. As on track 1, every member of the quartet develops his own interpretation of the piece, suggestions of danceability and/or sway inherent in the extroversion of the piece.

Making up for lost time while he contributed to the success of others’ groups, John Bailey’s third album continues his explorations into the jazz tradition, while he records with veteran musicians and spreads the humanitarian joy of jazz.

Artists’ Web Sites: www.johnbailey.com