By John Stevenson

Outsized and gruff-toned, the baritone saxophone has enjoyed a singular place in modern music. As band leaders or sidemen, Gerry Mulligan, Harry Carney, Cecil Payne, Serge Chaloff and Pepper Adams are numbered among some of the instrument’s most influential exponents.

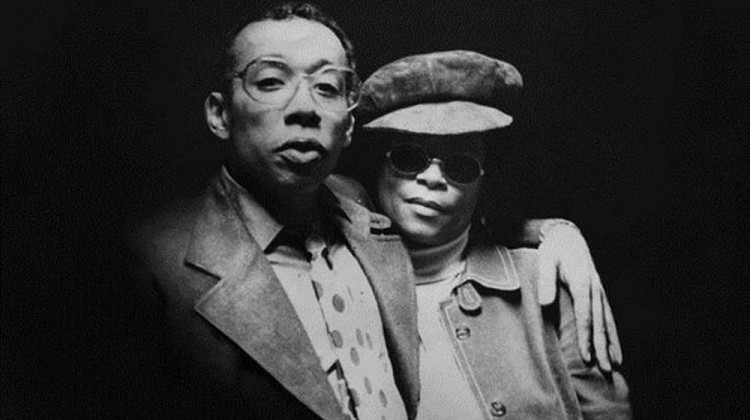

Fred Ho, who died on April 12 after a valiant battle with colorectal cancer, cut a distinctive figure as a baritone saxophonist and politically engaged activist.

Born in Palo Alto, California, on August 10th 1957 as Fred Wei-han Houn (he changed his surname in 1988), Ho was brought up in Amherst, Massachussetts, where his father taught political science at the University of Massachussetts.

He taught himself to play the baritone saxophone at the age of 14. Strongly impacted by the turbulent 1960s and the Black Arts Movement it spawned, he attended college classes taught by Archie Shepp and Max Roach– prominent African-American jazz musicians for whom artistic expression, race and politics were inseparable. In his 20s, Ho was briefly a member of the Nation of Islam and the I Wor Kuen, an Asian-American group inspired by the Black Panthers. A stint in the Marines was curtailed in 1975 after he fought with an officer who used a racial slur.

His close attention to Chinese, African-American and continental African music was buttressed by academic studies of race, culture and gender. He graduated with a degree in sociology from Harvard University in 1979. A combination of these experiences prepared him to become a musical innovator. Though he eschewed the term jazz (he thought it was pejorative and Eurocentric), Ho’s large ensembles, notably the Afro-Asian Music Ensemble, the Monkey Orchestra, the Green Monster Big Band and the Eco-Music Big Band were nonetheless heavily jazz-influenced, melding African-American and Asian rhythms.

The Underground Railroad to My Heart, exemplifies Ho’s uncanny ability to express himself on the baritone saxophone with panache, tenderness and tempestuousness. That 1993 album also reinterprets jazz standards (Juan Tizol’s ‘Caravan’ for example) and juxtaposes peculiarly traditional Chinese instruments such as the erhu and san hsien alongside woodwind and brass with exhilarating results.

Though he played in the bands of Gil Evans, Julius Hemphill and Archie Shepp, Ho produced over 15 recordings as a leader including other notable highlights such as Tomorrow is Now (1985), Once Upon A Time in Chinese America (2001), Snake-Eaters (2011) and Celestial Green Monster (2009). His prodigious output encompassed several operas, oratorios, a martial arts ballet and multimedia performance works. His opera Warrior Sisters: The New Adventures of African and Asian Womyn Warriors (1991), conceptualised an encounter between Yaa Asantewa, who led a 1900 Ashanti rebellion against British colonialism; the legendary Chinese warrior, Fa Mu Lan; 20th Century San Francisco Chinese-American women’s rights leader Sieh King King; and Black Liberation Army personality Assata Shakur.

His idiosyncratic musical tastes spilled over into his sartorial sensibilities. Ho was known for his colourful outfits, many of which he made himself. He was also a keen snorkeller and swimmer who was fascinated by oceans. His protégé, Benjamin Barson describes a snorkelling adventure with him in Hawaii:

“We explored the infinite fecundity of the underwater world, seeing varieties of fish that would fascinate colour theorists. I learned how this palette influenced Fred’s wardrobe; I also sensed a complex human being whose intense directives sometimes obscured a deeply sensitive individual; his compassion for the natural balance represented in diverse ecosystems motivated his seemingly dictatorial stance in the human world. After one particularly long snorkeling session in which we saw eleven giant sea turtles, he looked at me and said, ‘Every time I come here, I see the oceans dying. Without oceans, there are no humans.’”

Despite being diagnosed with colorectal cancer in 2006 and having to undergo several operations and courses of chemotherapy treatment, the last eight years of Ho’s life were prolific. He spoke openly about his illness and wrote two books about cancer: Diary of a Radical Cancer Warrior: Fighting Cancer and Capitalism at the Cellular Level and Raw Extreme Manifesto: Change Your Body, Change Your Mind and Change the World by Spending Almost Nothing! He described dealing with his illness in martial terms, a war that his body was a metaphor for the callousness of modernity with regard to human and ecological health.

Barson observes that towards the end of his life, “Fred became more concerned with environmental issues than the revolutionary nationalist questions of his past, though he by no means abandoned the latter. Rather, he attempted to create an innovative fusion by rejecting bourgeoise environmentalism in favor of cosmology that saw humanity and it’s ecosystems as one. To this end, he became a part time farmer during the summer months and was a committed Ecosocialist and self-proclaimed Luddite.”

Ho also received numerous grants during his career including such as the National Endowment for the Arts and the Rockefeller Foundation. Among his honours and distinctions were a 1996 American Book Award, a Guggenheim Fellowship and the 2009 Harvard University Medal of Arts.

Ho is survived by his mother Frances Lu Houn, and his two sisters, Florence Houn and Flora Houn Hoffman.