The mission of Resonance Records encompasses not only first-time releases of forgotten recorded performances by acknowledged jazz masters like Sonny Rollins or Wes Montgomery. It also provides opportunities for the current generation to discover jazz greats who didn’t attain comparable levels of public awareness.

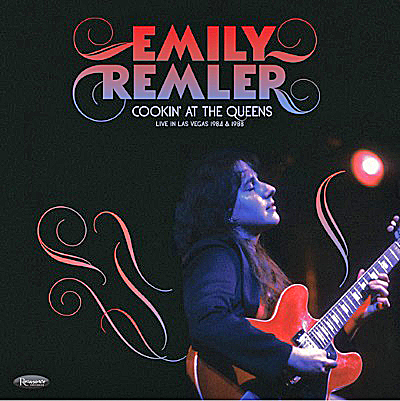

Guitarist Emily Remler eminently deserves appreciation by the current generation, as the producers of her album, Cookin’ at the Queens: Live in Las Vegas 1984 & 1988, realized.

The careers of a few jazz prodigies were unfortunately short, leaving listeners to speculate about what more they could have contributed to the genre, had they lived longer. But their impact remains, even today.

There was trumpeter Clifford Brown, gone at the age of 25. Bassist Scott LaFaro, gone at 25 too. Trumpeter Booker Little, at 23.

And more relevantly to Remler’s instrument, guitarist Charlie Christian, at 25.

Those four musicians, to name a few, received due recognition and remembrance because, at their young age, they had recorded on albums that received wide distribution, acknowledged respect from listeners and the media, and promotional strength.

Brown recorded with Max Roach (EmArcy) and Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers (Blue Note), among others.

LaFaro, on famous albums by Bill Evans (Riverside) and Ornette Coleman (Atlantic).

Booker Little, on his own albums and groundbreaking albums by Roach (Impulse!) and Eric Dolphy (Prestige).

And Christian, as a featured soloist on some of Benny Goodman recordings (Columbia).

Benny Golson’s immortal jazz standard, “I Remember Clifford,” provided a reminder of Brown’s talent every time that it was played.

Remler passed away at the age of 32, spurring speculation about what more she could have accomplished had her reputation continued to grow.

Fortunately, West Coast-based Concord Records, the label on which most of her albums were recorded, added Remler to its roster, supplementing releases by other Concord guitarists like Charlie Byrd, Kenny Burrell, Herb Ellis, and Barney Kessel. But Concord’s promotional reach didn’t equal that of Columbia or Atlantic.

Producer Zev Feldman—always on the cusp of rediscoveries, or perhaps as the catalyst for rediscoveries—has worked with jazz journalist Bill Milkowski and Resonance Records to remind jazz listeners that Remler belongs in the top ranks of jazz guitarists.

Super-sleuth that he is, Feldman found that tapes of Remler’s performances at the 4 Queens nightclub in the older part of the Las Vegas Strip still existed. Of course, he knew how to contact the person with access to them: sound engineer Brian Sanders, who recorded on KNPR-FM Alan Grant’s broadcast, 4 Queens Jazz Night from Las Vegas. Sanders had kept the tapes of those Monday-night performances.

With the Remler family’s permission, the result of Feldman’s investigations is another exquisite Resonance package, just as comprehensive as all the others. It provides over 2-1/2 hours of music from two of Remler’s engagements at the 4 Queens.

As is customary with Resonance releases, the accompanying booklet includes admiring comments from other musicians who performed with Remler, such as Eddie Gomez, David Benoit, and Peter Erskine. Other jazz musicians like Terri Lyne Carrington, Sheryl Bailey, and Mike Stern provide admiring comments. Milkowski’s ten-page essay in the album’s booklet provides a comprehensive biography about Remler. It’s evident that Milkowski listened analytically and joyfully to every second of her playing throughout Cookin’ at the Queens. He often describes to the minute and to the second an impressive passage, a technical signature of her own, or an unexpected artistic decision. To top it off, Cookin’ at the Queens features a transcript of Grant’s broadcasted interview with Remler.

Part of the excitement made possible by Cookin’ at the Queens is the ability for many to hear on her first release in 33 years this singular jazz guitar talent’s performances for the first time. Without preconceived expectations, the listener doesn’t know what the next ideas will be that she develops improvisationally.

Elements of Wes Montgomery’s, Pat Martino’s, and George Benson’s styles emerge occasionally, but Remler expanded upon their influences to create a style all her own. The 17 tracks on within Cookin’ at the Queens, though, evolve from Remler’s imagination as she sets up her own approaches to the music.

At the age of 24, Remler’s abilities were advanced enough to record on Concord her first album, Firefly, with a seasoned pro like Hank Jones. Her technique and feel had progressed even more when she recorded at 4 Queens at the ages of 27 and then 31—a year before she died. And so, Cookin’ at the Queens documents the results of her talent’s growth that impressed listeners and her peers.

What would a discovery/rediscovery of Remler’s talents reveal?

Without the space for a review as comprehensive as Milkowski’s essay, a few examples, though insufficient, may still suffice.

Appealing to the listeners stopping in from gambling in the casino, Remler included standard recognizable by everyone, including the medium tempo “How Insensitive” from her 1985 album with Larry Coryell, Together. The warmth of her single-note tones is immediately apparent in the first chorus, along with quick embellishments like grace notes, slight wavers, fade-outs of sustained notes, and self-made call-and-responses. During the quickened passages, she continues to build intensity throughout her improvised choruses of impeccable technique with tremolo picking and heartfelt chorded build-ups. Carson Smith’s resonant bass solo characterizes his participation in the 1984 quartet as equally melodic and thoughtful.

Likewise, Remler’s version of “Someday My Prince Will Come,” performed with grace and sweetness, emphasizes at first her close attention to comforting sonic effects through long tones akin to Jim Hall’s. Once again, Remler’s performance attains accumulating power as she alternates staccato picking with sustains, the initial laid-back melodic ease acceding to her faster choruses of improvisational interpretation. At 4:20, she abandons her direct fond attention to melody by altering the guitar’s timbre.

Remler pays tribute to some jazz masters by adventurously combining Miles Davis’s “So What” with John Coltrane’s “Impressions.” Immediately, her 1988 quartet begins “So What” at an attention-getting furious pace, Smith’s quarter notes scurrying beneath her lead. Remler reinforces the idea of combinations by following the first chorus of “So What” with one of “Impressions.” Then, the two famous compositions mix to feature the originality and imagination of Remler. Just as remarkable is her flawless technique, as inspiring as the revered talents of her influences, Montgomery and Martino. Isolating the appreciation of her talent, Smith and drummer John Pisci drop out at 4:38. Then, Remler plays an extraordinary three-minute solo for the ages, the moods she conveys changing even within that short amount of time. Not only does she interpret with her usual single-note call and chorded response, but also, she assumes walking bass lines the evolve into improvisational lines. The drums and the bass enter again at 7:25 after Remler precedes their re-entry with forcefully strummed rising chords.

Just as fascinating are Remler’s versions of other jazz standards like Sonny Rollins’s “Tenor Madness,” Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers’s “Moanin’,” or Todd Dameron’s “Hot House.” As the first track of Cookin’ at the Queens, “Moanin’” provides a natural opportunity for Remler’s to open with an infectious swing for a first impression of her talent. “Tenor Madness” could just as well be termed “guitar madness.” Remler’s 1984 quartet soars through an exciting, supercharged interpretation of almost five minutes. Her energy doesn’t flag at the end of the set as if she’s as excited to perform as she was at its beginning. Pianist Cocho Arbe’s solo chromatically rises excites as he picks up on her energy. Once again, Remler inventively combines jazz compositions, this time blending “Hot House” with “What Is This Thing Called Love?” both of which were written over the same changes. As with “So What”/“Impressions,” she alternates at the beginning the melodies before they blend into a single creation of her own, after which Arbe develops his own solo. Drummer Tom Montgomery trades fours with her.

Cookin’ at the Queens includes Remler’s tributes to Martino and Wes Montgomery. With dynamic swinging force and precise articulation, Remler reminds listeners of Martino’s singular style on “Cisco,” a piece based on blues changes from his 1967 El Hombre album. But as guitarist Steve Masakowski recalled in Jazz Times, Remler competitively and diligently worked to master Montgomery’s famous octave technique, as well as other elements of his style.

Each of the CD’s in the Resonance release features a blues by Montgomery. It remains to be confirmed if Remler included a Wes Montgomery piece in every set, similar to Fred Hersch’s inclusion of a Thelonious Monk composition on every recording. First, there’s Montgomery’s familiar “West Coast Blues,” strolling at a medium tempo. It demonstrates Remler’s seamless facilitation of harmonic changes, her ability to recall musically Montgomery’s style, and her command of his technical signatures like his original use of octaves. The 8+-minute track of Montgomery’s “D-Natural Blues” concludes not only the 1988 set at the 4 Queens, but also the entire album. Its relaxed blues groove features Smith’s final solo before and after Remler’s eloquent improvisations that contrast with her hard bop chops. Taken in its entirety, the album demonstrates not only her versatility, but also her complete immersion into the music expressed through her skillful technique.

Once again, Resonance Records has put another exclamation point on the career of an innovative jazz musician. Emily Remler’s discography, thought until now to be complete, still grows decades later with the release of Cookin’ at the Queens.

The discovery/rediscovery of her talent continues.

Label’s Web Site: www.ResonanceRecords.org