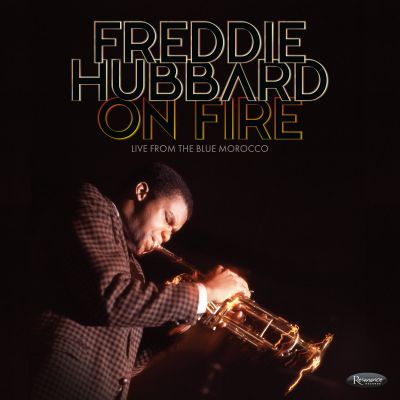

No doubt, the owners of the Blue Morocco in the Bronx, Sylvia and Joe Robinson, didn’t foresee the need to stock up on extra fire extinguishers before Freddie Hubbard played there on April, 10, 1967, just three days past his 29th birthday.

Once Hubbard started playing, jets of fires immediately shot out of the bell of his trumpet without even the smoldering or the smoke of a gradual buildup to provide a warning.

The Robinsons needn’t have worried, though. Hubbard’s flames were a controlled burn. Yet the heat continued throughout this extraordinary session—documented now on one of his few early albums that were recorded before a live, possibly unsuspecting audience, members of which perhaps being unprepared for the heat that a Hubbard performance stoked.

There were no studio constraints. Hubbard and the members of his quintet blazed through this landmark performance. As always, Hubbard was the indefatigable musical force who pulled the other musicians up to his level.

Despite the frequent use of fire as a metaphor for Hubbard’s early virtuosic style, few other comparisons are sufficiently descriptive.

With youthful vigor and ambition; irrepressible talent that becomes immediately obvious once Hubbard starts to play; astonishing technique refined during his nine years since arriving in New York; and his revelatory unlocking of harmonic possibilities unimagined by other musicians—Hubbard’s musical curiosity, enthusiasm, and showmanship…unmistakable in his early recordings…virtually blazed with astounding musical invention and his boundless joy of performing music.

Even a jazz icon who helped develop the musical language of bebop, Dizzy Gillespie, believed that Hubbard was one of the world’s greatest trumpet players.

The convergence of all these elements makes Resonance Records’s never-before-released recording, On Fire: Live from the Blue Morocco, an essential addition to Hubbard’s discography.

Fortunate are listeners for the fact that recording engineer Bernie Drayton saved the tape of Hubbard’s Blue Morocco performance. Unaware that this wouldn’t be just another broadcast, Drayton had set up his audio equipment above the bar in Joe Robinson’s office for DJ Del Shields’s local jazz radio program.

The deceptively calm first twelve bars of “Crisis’s” descending harmonies and long tones gave way at 1:21 to the instantly identifiable forces of Hubbard as his thrilling technique and imaginative improvisational ideas astounded the audience.

Hubbard included more of his compositions throughout the event— “Up Jumped Spring,” “True Colors,” and “Breaking Point”—all of which had been written early in his career and had been insufficiently recorded up to that point.

The members of Hubbard’s working group on this recording were developing their own fresh ideas about how to approach his compositions that later would become jazz standards.

Hubbard completes the album’s recording of “Crisis” with his own speaking voice as he promotes his 1961 Blue Note album, Ready for Freddie (on which jazz legends Wayne Shorter, McCoy Tyner, Art Davis, and Elvin Jones played).

The uniqueness of On Fire arises from its capture of Hubbard playing before a audience without a studio’s constraints of time or a producer’s interference. The entire Resonance package offers almost two hours of unfettered playing as Hubbard and all the other members of his group stretch out with spontaneity and heightened energy.

The quintet played “Crisis” as long as they wanted, allowing a gradual slowdown at the end as Hubbard lowers his pitch from his earlier thrilling high notes to his quieter growls.

The initial delicacy, the lower volume, and the spareness of Hubbard’s muted solo on “Up Jumped Spring” contrasts directly with the force of “Crisis.” Bennie Maupin recalls in his printed interview within On Fire’s package that Hubbard’s intensity required Maupin to practice often “to keep up with him.” Even on a medium-tempo waltz like “Up Jumped Spring,” Maupin delivers a memorable solo of dynamic variation, unrepeated ideas, and a long build-up.

Unlike the many studio recordings of “Up Jumped Spring” after it became a jazz standard, at the Blue Morocco, Hubbard’s group played through numerous choruses for over seventeen minutes. Indeed, the average time for all the tracks within On Fire is just under sixteen minutes.

The Hubbardian inferno returns on “True Colors.” Maupin’s remarks about the necessity for preparation to perform in Hubbard’s group becomes clear. Only the highest level of jazz musicians would have been able to “keep up.” Drummer Freddie Waits sets that piece’s blistering pace from the start and at 10:00 takes his own solo, as if a fuse were finally lit and all his supportive energy were allowed finally to explode from its pyrotechnic shell.

Hubbard established the feel of “Bye Bye Blackbird,” the release’s longest track at just under 24 minutes, as that of a hybrid street march/on-stage club performance. Bassist Herbie Lewis backs him with walking four’s of meters shifting in and out of double time. Waits follows Hubbard’s moods with martial cadences and then fiery colors. Only after pianist Kenny Barron had accompanied and absorbed Hubbard’s and Maupin’s successive solos throughout 13:40 minutes does he downshift. Barron cuts the meter in half, putting his own stamp on the piece with oblique harmonies and lyricism. Lewis and Waits deserve credit for immediately sensing Barron’s contrarian intentions and adjusting accordingly.

This was an amazing quintet of members who listened to each other intently and supportively throughout the event at the Blue Morocco. As if to prove the point, Hubbard and Maupin trade eights with Waits before they swap in-the-moment ideas with each other over Lewis’s pedal point at the end of “Bye Bye Blackbird.”

Generously, Hubbard featured Lewis on bassist Bob Cunningham’s “Echoes of Blue,” a composition of diminished chords. The imperative to listen to Lewis’s quieter instrument provides an interlude within the set’s other tracks that feature the intensity of Hubbard’s uncontainable fervor. But at 8:12, Hubbard’s clarion entry announces his intent to raise the temperature of “Echoes of Blue,” his thematic expansion giving rise to a leisurely yet still intense interpretation.

Though one might expect Hubbard’s arrangement of “Summertime” to coincide with the Gershwin jazz opera’s original portrait of casual wonder and reassurance, he had other ideas. After his plangent bravura introduction, Hubbard re-emerges in a lighter mood at exactly one minute after the piece commences. Though Barron’s and Lewis’s jazz-waltz vamp anchors the moderato pace and keeps the rhythmic mood relaxed, Hubbard raises the temperature with each chorus. Eventually, the rhythm section follows Hubbard’s lead as the pace slightly accelerates. The quintet’s growing exhilaration is palpable.

As he had done, though briefly, at the end of the Resonance package’s first disk, Hubbard concludes the entire concert with the blended calypso/hardbop feel “Breaking Point,” the background of which allows him to recognize the group’s musicians and to thank the audience. The audience once again could appreciate this influential trumpeter’s youthful vitality. Its members’ talents already were heralded as singular voices in the continuing development of jazz vocabulary.

Unfortunately, I never heard Hubbard play in person while he was in his prime. Nonetheless, I couldn’t pass up the opportunity to hear David Weiss’s New Jazz Composers Octet play his music at the Iridium. Sadly, as a presence, Hubbard, an acknowledged colossus of jazz, was reduced to nodding his approval and bestowing his blessing to the group of admiring young musicians on the stage. Hubbaard couldn’t perform because of the damage to his lip that Kenny Barron describes in On Fire’s booklet.

Nevertheless, I was fortunate at least to have soaked in the sizzling charged atmosphere within Freddie Hubbard’s orbit, even as the audience’s hearts went out to him.

Fellow trumpeter Jeremy Pelt, who gave Hubbard his last trumpet, states in On Fire’s booklet that Hubbard, an irresistible giant of jazz in the sixties, seventies, and eighties, became reclusive after he was unable to play in the nineties.

Resonance Records’s release of On Fire: Live at the Blue Morocco reminds listeners once again of Freddie Hubbard’s essential contributions to jazz and of his remarkable musical stature.

Label’s Web Site: www.resonancerecords.org

Artist’s Web Site: https://freddiehubbardmusic.com