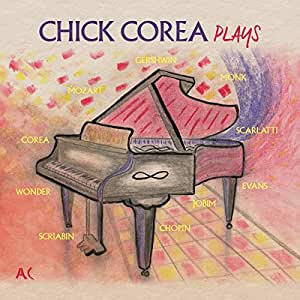

Chick Corea plays solo. Chick Corea plays Monk. Chick Corea plays bossa nova. Chick Corea plays Mozart. Chick Corea plays concert halls. Chick Corea plays Stevie Wonder. Chick Corea plays duets. Chick Corea plays Gershwin. Chick Corea plays jazz. Chick Corea plays Chopin. Chick Corea plays tone poems. Chick Corea plays Jobim. Chick Corea plays remembrances. Chick Corea plays Scarlatti. Chick Corea plays Children’s Songs. Chick Corea plays pop. Chick Corea plays Yamahas. Chick Corea plays Bill Evans. Chick Corea plays spontaneous improvisations. Chick Corea plays Kern. Chick Corea plays auditoriums. Chick Corea plays classical. Chick Corea plays Corea. Chick Corea plays. And plays. And plays. And plays. And keeps playing.

With a lifetime of piano playing behind him, Chick Corea continues to summon his childhood joyfulness and his dancing touch and his joyous harmonies. More importantly, Chick Corea, music being as fluent a language for him as speaking, shapes his future with ever-more fascinating performances, as he creates new groups to express his latest ideas or as his unflagging enthusiasm is matched by duet or solo albums.

Chick Corea’s most recent addition to his more-than-half-century-long discography comprises a series of solo concerts throughout the United States and Europe.

No, Corea isn’t playing solo because of the demands of the post-COVID-19 world, which descended fast upon us. He has established an orchestral sound of his own in concert after concert before sold-out audiences, audience members then behaving in ways that are presently unthinkable. They–gasp!–sat shoulder to shoulder with no social distancing! And they wore no masks!

The audiences were still able in many-months-ago pre-COVIDian times to enjoy the special pleasures that presentations of priceless art provides. How quickly the world has changed. How creatively precious in its unpredictable delights Corea’s music remains. His good fortune was, and ours is, that Chick Corea Plays was recorded before the world was transformed into one where packed auditoriums are considered with suspicion, if not forbidden. And the recording can be played masklessly at home without worry about the spread of a fearsome virus. Such prescience Corea had.

An successful entertainer before a packed concert hall, Corea let his fingers do the talking through much of Chick Corea Plays. However, the album assembled from the various performances includes private tidbits that he shared with his audiences to introduce the pieces he played, to break up his piano playing with a human voice, and to draw in the audience with confidences. Do you know, for example, that, as a young child, Corea used to play “portraits” of his large family of cousins, aunts and uncles “to make fun of them?” This childhood delight still happens as the 79-year-old Corea favors others with his portraits. In the case of Chick Corea Plays, he paints music images of audience members Henrietta (delicately melodic) and Chris (playfully active in a lower register), whose lives now are documented forever in a Corea recording.

In fact, all of the second disk in the two-disk package of Chick Corea Plays involves the theme of childhood wonder and fun. Stevie Wonder’s “Pastime Paradise,” with introductory swirling, sweeps and octave leaps, appropriately starts 55 minutes of musical reminiscences and sonic immersion in innocence and exploration.

Another of Corea’s childhood remembrances is the sharing of his grandfather’s piano with family members as they played duets. Well, Corea still plays duets, and not only entire albums of duets with the likes of Herbie Hancock, but also with audience members who dare to sit down at the same bench. One would think that the two piano players who played fearlessly the duets with Corea were pre-selected. Corea says that they were not; they were just attending his concert. But it turned out that Yaron Herman and Charles Heisser are professional pianists who during their duets with him not only followed Corea’s lead with their own stylistic responses, but also contributed ideas of their own that Corea elaborated upon.

The childhood remembrances of Disk 2 are complete as Corea performs eight of his twenty “Children’s Songs” from the 1984 ECM album, on which he cited Béla Bartók as a primary influence. Individually as different as a child’s personality would be, the short “Children’s Songs” on Chick Corea Plays–which are little musical portraits, or tone poems as well–include the “Children’s Song No. 1’s” dissonance of a tonic left-hand pattern with a mischievous off-kilter melody whose rhythm doesn’t precisely match the playful mid-register pattern either. Or “Children’s Song No. 10,” more delicate than “No. 1” includes more arpeggios and harp-like sustains.

Things would appear to be more serious as Corea begins Disk 1, as well as beginning one of his concerts (after he encourages the audience to sing), with Mozart’s “Piano Sonata in F, KV332 (Adagio),” revealing the fact that Corea’s classical interests expand beyond Bartók. Improvisation being the act of instantaneous composing, Corea’s intention was to honor some of his favorite classical composers/performers. But he also honors his jazz, Broadway and Latin composers too. He does that in such a way that he combines classical pieces with those of more contemporary composers to help his audiences understand the commonality of compositional excellence. And so, Corea combines, at least sequentially, Mozart’s sonata with his gorgeous rendition of George Gershwin’s “Someone to Watch over Me.” He does it again when Jerome Kern’s “Yesterdays” follows Domenico Scarlatti’s “Sonata in D Minor K9, L413 Allegro.” By the time the audience understands Corea’s point, he creates a medley of Bill Evans’ “Waltz for Debby” and Antonio Carlos Jobim’s “Desafinado,” connected by an brief improvisation instantly identifiable as one of Corea’s. Chick Corea should be gratified that jazz listeners can recognize his style after just a few measures of playing.

Another jazz pianist/composer in the same category is Thelonious Monk, belatedly recognized after his passing by jazz pianists who are endlessly exploring by Monk’s own sense of playfulness and originality. Corea pays tribute to Monk’s one-hundredth birthday with a medley of “Pannonica,” “Trinkle Tinkle” and “Blue Monk.” Even as Monk’s individualistic senses of rhythm and harmony remain, Corea puts his stamp on Monk’s music with his own touch and stylistic identifiers.

Monk played while he played. Mozart played. Gershwin played. Scarlatti played. Evans played. Jobim played. Chopin played. Kern played. Scriabin played. Stevie Wonder plays. And Chick Corea Plays. And plays. And plays and plays.

Chick Corea has played piano ever since his formative childhood playing. And Chick Corea still captures the child within us.