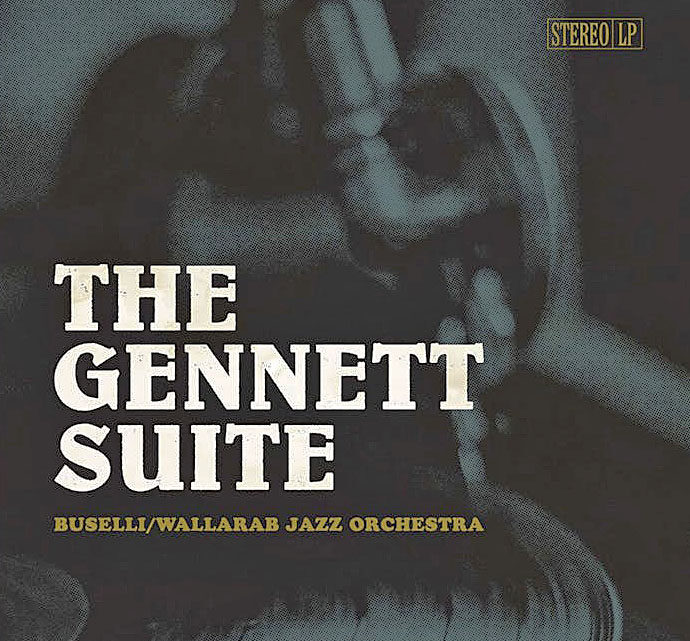

The Buselli/Wallarab Jazz Orchestra’s recording of The Gennett Suite is a remarkable event.

Not only because of co-founder Brent Wallarab’s imaginative interpretations of influential early jazz recordings at Gennett’s studios. But also because of his vision for developing an eleven-part suite of four movements, lavishly produced, that honors the importance of Gennett Records in the development of jazz.

Much recognition, and even a few entire books, emphasize the contributions of other early jazz labels, like Dial, Savoy, Decca, Bluebird, Atomic, Vocalion, Brunswick, or Okeh.

Not so much for Gennett Records.

Though less recognized, Gennett Records produced equally significant recordings in the middle of the great Midwest.

Gennett Records began as an outgrowth of a manufacturing facility, the Starr Piano Company, founded in 1872 in Richmond, Indiana. Starr Piano Company happened not to be located near a major waterway or railroad line. In the absence of sufficient, efficient, and economical recording devices, many homes in the late nineteenth century contained pianos so that one or more residents could play sheet music of popular, classical, or religious music.

Technology changed, and so did Starr. Its record-making initiative was named after the piano company’s owners, the Gennetts.

Less recognized as well was Gennett Records’s success in challenging the patent for Victor’s innovative record-making technology. As a result, in 1922 Gennett Records was able to make its own records without challenges from Victor. But, also significant was the fact that Gennett Records’s patent challenge opened the door for other record companies to document early jazz talent.

And now, Wallarab’s suite calls attention to the importance of Gennett Records’s early recordings by featuring fond re-imaginings of the music of four of the company’s most famous musicians: Joe Oliver, Bix Beiderbecke, Hoagy Carmichael, and Jelly Roll Morton.

The confluence of Gennett Records’s newly available recording technology—and its relative proximity to Chicago, the riverboat towns of Cincinnati and Louisville, and Indiana University (from which Carmichael graduated)—contributed to Richmond, Indiana’s reputation as a go-to place for making recordings. Indiana University continues to provide a professional musical environment, whoseon-campustalent was available to participate in the recording that honors the label.

Items of Gennett Records’s musical significance include Louis Armstrong’s first existing recorded solo, Indiana-native Carmichael’s first recordings (including his first instrumental version of “Star Dust”), and Beiderbecke’s first recording as a leader. In addition, Gennett’s studio documented early-in-their-careers performances by Tommy Dorsey, Sidney Bechet, Gene Autry, Lawrence Welk, and Guy Lombardo, and Duke Ellington.

Wallarab is the right person at the right time to produce The Gennett Suite. Having received his Master of Music degree from Indiana University, Wallarab joined the Smithsonian Institute, where he became the lead trombonist for the Smithsonian Jazz Masterworks Orchestra—and where he transcribed more than 300 jazz masterworks by iconic jazz composers like Gil Evans, Duke Ellington, and Fletcher Henderson. Thus began his passion for discovering early jazz works previously unrecognized or under-appreciated.

A few years later, at the suggestion of jazz master David Baker, Wallarab moved from Washington D.C. back to Indiana, where he and Mark Buselli, a fellow educator at Ball State University, formed the 18-piece Buselli/Wallarab Jazz Orchestra. Thirty years and ten recordings later, this jazz orchestra continues to express its passion for jazz tradition throughout college classrooms, in clinics at public schools in Indiana, and with its 1000+ performances at Indianapolis’s Jazz Kitchen.

Wallarab divides The Gennett Suite into four movements, each to emphasize the importance of ground-breaking musicians whose early recordings took place in Richmond, Indiana.

Movement 1, “Royal Blue,” consists of three influential blues compositions: “Tin Roof Blues,” recorded in Gennett’s studios by the New Orleans Rhythm Kings; “Chimes Blues,” which commemorates Louis Armstrong’s first recorded solo; and “Dippermouth Blues,” which includes Joe Oliver’s influential Gennett Records solo.

The comprehensive liner notes by David Brent Johnson—host of Night Lights and Just You & Me on Indiana University’s WFIU-FM station—provide astute analyses of all the tracks in much more space than a review allows.

Suffice it to note that The Gennett Suite’s 17-minute “Introduction,” which consists of “Chimes Blues” and two versions of “Tin Roof Blues,” showcases from the very start the complexity of Wallarab’s arrangements. Moods shift, rhythms accelerate and decelerate, strong melodic lines emerge and fade, and re-harmonizing deepens the backgrounds’ shadings under color kaleidoscopic dapplings. The first three minutes of the “Introduction” are indeed introductory as ominous low-brass sustained tones set up over shifting trombone voicings trumpeters Mark Buselli’s and Jeff Conrad’s wails. A theme throughout much of The Gennett Suite comprises Wallarab’s blues harmonies emphasizing the flatted third. Then, boom! At :52, a contrasting “Introduction” rhythm, heavy on the forceful low-register quarter-note accents, occurs that simulates a locomotive’s power at the engine’s start—an often-utilized musical device in early jazz.

And then, at 1:24, the mood changes again. Walking bass lines support Ned Boyd’s presentation on baritone sax of the “Tin Roof Blues’s” melody. Eventually, it becomes evident, despite the changes, that the first four minutes consist of expansions upon the “Introduction’s” initial motive. The orchestra’s volume rises, and the trumpets exclaim with upper-register clarion force. The heightening tension eases when Boyd solos a second time over pianist Luke Gillespie’s moving-tenth blues chords. Thereafter, these blues undergo a wide variety of colors and feelings.

Rather than continuing to adhere to the first Part’s standard interpretations of the blues as the 1920’s are recalled, “Tin Roof Blues, Part 2” develops jubilantly and majestically in in a meter of three. Polyphony, polytonality, and post-bebop progressive voicings serve as the foundation for Tom Walsh’s tenor saxophone solo.

Joe “King” Oliver’s “Chimes Blues” seamlessly evolves from “Tin Roof Blues” to complete the “Introduction,” as soprano saxophonist Greg Ward floats through the brass-led accents and the heavy swing. “Introduction,” a noteworthy achievement in itself, continues the call-and- response musical conversation as Ward and Buselli conclude with blues-drenched phrases.

From the start, drummer Sean Dobbins’s festive second-line rhythm dances into “Dippermouth Blues,” the second and last piece of the “Royal Blue” movement. Though the original Gennett recording featured Oliver, Wallarab’s arrangement immerses the orchestra in Crescent City celebrations as trombonist Andrew Danforth and tenor saxophonist Todd Williams elevate the proceedings with their own ebullience. Wallarab cleverly weaves into the arrangement quotes from “Tin Roof Blues” and the original “Chimes Blues” recording. Energy and rhythm are ever-present elements, hard accents on the last quarter note of every two bars sparking the orchestral might.

Movement 2, “Blues Faux Bix,” celebrates the importance of “Bix” Beiderbecke’s first recordings, pressed by Gennett from a 1925 session in which Tommy Dorsey participated. Wallarab arranged the piece to allow Buselli to capture Beiderbecke’s lyrical style and distinctive tone. As Buselli soars melodically throughout, Wallarab provides the comforting cushion of lower-brass movement in broad harmonies. A saxophone soli of swelling and contracting dynamics reinforces Amanda Gardier’s written improvisational lines, which she plays on alto sax in unison with the sax section. Less comforting, and more vigorous, is “The Jazz Me Blues,” begun as a swap between the band’s warm, sustained quote of the song’s first four bars and Dobbins’s succinct reply. Wallarab’s electrifying treatment of the piece serves as a springboard, in varying moods and tempos, for successive instrumentalists’ exuberant solos. The strength of Jeremy Allen’s bass work—which underpins the performances of “Blues Faux Bix” with firm support—emerges as a poignant solo with glides and bluesy quarter tones in the next track, “Interlude.” As if in a continuation of “Interlude,” Allen develops a strolling vamp. In reality, his vamp becomes the start of “Blues Faux Bix’s” last track: Jelly Roll Morton’s “Wolverine Blues,” another spirited showcase for orchestra members’ solos.

Movement 3, “Hoagland,” (which incorporates Hoagy Carmichael’s given first name as its title), appropriately segues from Beiderbecke, Carmichael’s stylistic inspiration and his associate from Indiana University. “Star Dust,” the most ethereal, abstract, thoughtful, and evocative of Carmichael’s songs—first recorded in Gennett’s studio in 1927—receives Wallarab’s dreamy interpretation in three, similar in meter to “Tin Roof Blues, Part 2,” but entirely separate in mood. At first spare, pensive, and abstract as Gillespie’s flowing, Impressionistic accompaniment backs Ward’s moving saxophone solo, “Star Dust” unfolds in subdued harmonic richness as a song inspired by improvisational intervals receives improvisational embellishments. Johnson is perceptive to compare The Gennett Suite’s characteristics to the naturalism, beauty, fond and evocative sense of place, and harmonic complexities of another landmark recording, Maria Schneider’s The Thompson Fields. Both are beyond category as they present disparate soundscapes expressing the profound complexity of life in Middle America—a complexity that may be surprising to some who live outside that environment. “Hoagland” continues with two versions of Carmichael’s “Riverboard Shuffle,” which Beiderbecke recorded on the Gennett label in 1924. The first up-tempo version features Dobbins on drums and John Raymond on trumpet. Tenor saxophonist Williams interprets “Riverboat Shuffle, Part 2” as a more relaxed stroll over walking bass lines and orchestral interjections. Allusions to, and the spirit of, “Part 1” again invigorate the track at 4:49, Williams, Raymond and Dobbins trading lines to wrap up “Riverboat Shuffle.”

Movement 4, “Mr. Jelly Lord,” recalls Jelly Roll Morton’s July 1923 piano solo recording of “Grandpa’s Spells” during a joint Gennett session with the New Orleans Rhythm Kings. A larger-than-life individual whose unorthodox lifetime experiences became legendary, Morton nonetheless, through pianistic virtuosity, facilitated the stylistic transition from ragtime to jazz. His most famous composition, “King Porter Stomp,” eases on down with a medium-tempo shuffle. Seamless allusions like “No Moon at All”; contrasting brass-shouted calls and saxophone-whispered responses; a breakout into a hard swing; and droll devices like Gillespie’s upper-register noodling and Rich Dole’s how-low-can-he-go? bass trombone solo enliven the orchestra’s performance. Despite its extroverted entertaining nature, “King Porter Stomp” ends gorgeously with the saxophones’ atonal allusive phrase over a lower-brass chord that blossoms in volume to the finish. “Grandpa’s Spells” concludes “Mr. Jelly Lord,” as well as the Suite, in a buoyant updating of upswept orchestral movement, broadly chorded accents, Dobbins’s tripleted build-ups, and advanced jazz harmonies.

Wallarab notes that he includes Morton’s “Spanish Tinge” as an element of the arrangement. Of “Grandpa’s Spells.” As a result, consistent with the rest of The Gennett Suite, “Grandpa’s Spells,” doesn’t juxtapose, but rather it blends, techniques from some of the first jazz recordings of the twentieth century with the orchestral colors and textures developed from ensuing influential bands and recordings.

As befits the importance of Gennett Records’s contributions to the development of jazz, the Buselli/Wallarab Jazz Orchestra’s two-CD recording of The Gennett Suite is packaged within an impressive sixty-page booklet. Its elaborate attention to detail and respect for the music develop from comprehensive essays by Johnson and John Edward Hasse, Curator Emeritus at the Smithsonian Institution, author, and founder of the Smithsonian Jazz Masterworks Orchestra.

The Gennett Suite itself is a masterwork.

Artists’ Web Site: bwjazzorchestra.com

Label’s Web Site: patoisrecords.net