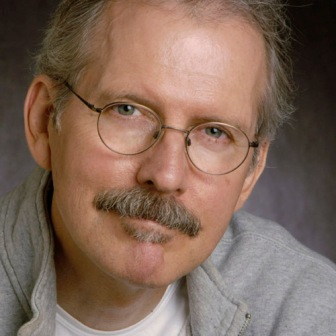

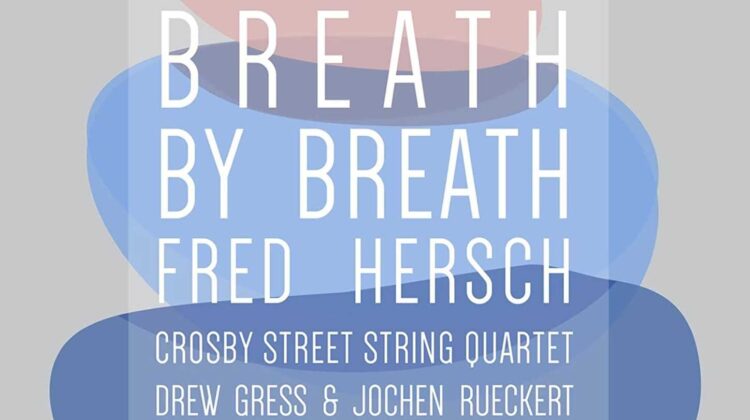

Fred Hersch’s My Coma Dreams positions him even higher in iconic status among jazz musicians as it elevates the traditional role of jazz musician from concert stage and nightclub presence to that of a multimedia artist with profound insights to share. In Hersch’s case, these insights involve some of the conditions that mankind has been pondering throughout its existence—the contrast between fantasy and reality, the nature and the meaning of suffering, vitality and evanescence, the power and the insufficiency of love, life and legacy, the struggle between fate and free will. Yes, all of that and more are contained in My Coma Dreams, which allows Hersch to convert a near-death experience into an incomparable work of art.

The performance proceeds in a relatively straightforward narrative with fanciful digressions written by Elmer Gantry composer Herschel Garfein. My Coma Dreams describes Hersch’s experiences—as well as those of his partner, his mother and his doctor—as he progressed from septic shock into an induced coma. And then very gradually, back to consciousness. And just as gradually, toward an extraordinary artistic achievement.

The story of Hersch’s recovery is just as remarkable as that of his infirmity. At first not even being able to hold a pen, he had to regain much of his ability to play the piano. However, My Coma Dreams focuses on the alternative state of mind that many people unfortunately experience—but don’t wish to, or don’t have the ability to, describe. The comatose state, of course, causes alarm among the victim’s loved ones due to the loss of communication and the uncertainty of outcome. The dramatic tension and the selflessness of My Coma Dreams arise from the fact that the remarkable actor Michael Winther assumes all of the feelings and actions of all of the characters, and not just those of Hersch himself.

Winther’s versatility of performance, emotionally charged singing and dramatic narrative presentation make such a strong impression during the first viewing of My Coma Dreams that he seems to be the center of the work, accompanied by Hersch’s eleven-piece ensemble. But a second calmer consideration of My Coma Dreams reveals that it contains much more music, written of course by Hersch, than first realized. Indeed, all of the elements of My Coma Dreams, including Sarah Wickliffe’s animation and Eamonn Farell’s computer images, mesh to create a total creative effect of characterization, narration, thematic depth, visual delight and musical appeal. That appeal, created so effectively by Hersch whenever he performs on any recording or in any venue, transcends the limitations of words or sight as it connects with the soul of the listener.

My Coma Dreams is unlike any previous work by Hersch, but then it’s his most personal as well. Hersch’s illness became progressively worse—from a cough without a fever to a collapse at home to a strapped-down ride to the hospital to the shut-down of organs to induced coma to a six-week suspension of consciousness. Accordingly, the music moves from free improvisation with John Hébert’s wild pulsation of bass to a tango to Thelonious Monk references to a jazz jam session to Adam Kolker’s saxophone melody about the knitters and then finally to Hersch’s solo of “The Orb” as his loved ones pull him back to consciousness.

The knitters. Garfein’s references to the women who “sit and knit and whisper” and the fact that “we end as we begin” universalize and deepen Hersch’s experience. “We, under a spell / Say nothing… / As if our fate…was knitted in the room below.” The terrifying unspoken truth of My Coma Dreams is that a similar experience could happen to anyone. Winther’s alternate personality as Hersch’s partner Scott depicts the horror of everyone who cares for a person undergoing a health crisis. For Winther as Scott noticed that Hersch “lost thirty pounds,” declined into a “persistent vegetative state” and “was less and less there” as his head became “just a skull.”

However, My Coma Dreams isn’t totally about melancholy or loss or shock. Actual delight ensues, strange as it may seem. Hersch and Garfein wisely balance the discord of medical decline with the harmony of kindness, particularly during a beautiful solo violin passage by Laura Seaton. The third word of the work’s title, “Dreams,” allows for fanciful self-entertainment within the mind, even as it’s disconnected from family, medical professionals and community. Hersch’s dreams create a scene wherein he and Monk, who is caged within a dream too, compete to write a tune with the reward of freedom for the first to finish. Winther, in the person of Hersch, describes Hersch’s affinity for Monk’s music by explaining his fascination for Monk’s “rhythmic dancing” and “the unexpected” to the accompaniment of “I Mean You.” Other lighter moments occur, like his “Jazz Diner,” as visuals of diner menus appear on the screen, Winther then being in spoken cabaret mode. As Hersch’s jazz theater production traverses through the subconscious images recalled from his coma, he visualizes children surrounding his bed and those darned knitters seen from above. In essence, Hersch’s dream-state experience during his coma produces the purest form of creativity without constraints or worry or expectation. The images aren’t crafted through external means such as voice or instruments or pen or movement or computer. They just are.

Hersch’s experience led him, along with his professional collaborators, to set up a unique form of expression containing continuing moments of anguish and beauty and relief. It combines the conventions of a concert, the entertainment of a theatrical production, animated fancy, story-telling, classical chamber music, poetry and a jam session. The relief of My Coma Dreams happens as the doctor gradually withdraws medications, causing Hersch first to stir, to cross “the hazy border between the unconscious and waking,” to undergo rehabilitation, and then to recover. Part of that recovery comes when the therapist advises Hersch to look in a mirror and “don’t look away.” Hersch’s response to his real, undreamt image: “This can’t be me.” And then, near the end of the performance, and in one of its most powerful moments, Fred Hersch stands up from the piano and walks to center stage to become the reflection that Winther as Hersch sees in the mirror.

At the end of My Coma Dreams, as in Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, the third knitter—Atropes, who cuts the fabric of life with her scissors—remains absent. How fortunate we all are that the Moirai’s thread of life continues unsevered so that Hersch could raise the level of his art to that of immortality. Free will prevailed.

2014

Proceeds from sales of the DVD go to: http://www.treatmentactiongroup.org/mcd

Artist’s site: www.fredhersch.com